A Passion Play

Peter Peryer. Self Portrait, 1977

A PASSION PLAY

Peter Peryer obituary by Peter Ireland for PhotoForum

18 December 2018

Peter Peryer’s unexpected death has placed a full-stop at the end of a sentence that seemed capable of containing many more phrases. This early demise raises the question of what the difference might be between a very good artist and a possibly great one. On the evidence, it seems a general principle that most artists do their best work (energised, adventurous) in their twenties and thirties, and in their forties reaching a kind of cruising height in their practice that, at best, is consistent rather than surprising. At worst it can suggest a desperation to maintain a profile or a dependence on an established “signature” to mask what might be termed a creative sterility. Examples abound.

The adjective “great” in these relentlessly promotional days is applied like seed to a paddock – a phone company has just announced they have “great deals over the summer” – but we might still expect of “the best” artists that throughout their lives they might remain energised and adventurous, their work plumbing ever more sonorously the depths of our culture and human experience. We could think of McCahon’s late, brave descent into a pitiless bleakness, shorn of much hope, but with an astonishing economy of means. Or Woollaston’s stretching of wings in his late, expansive panoramas, and, Gordon Walters’ relentless investigation of form and scale. Not many examples of sterility abounding there.

Form and scale were central to Peryer’s project too, and just as those elements in Walters’ work related to Modernism, Peryer’s related to photography: each artist in their own way distilling the specific nature of their chosen medium, undistracted by the hum of current fashion and the seductions of the market-place. In this respect it may not be coincidental that Walters lived in Christchurch, Woollaston at Riwaka, and Peryer in New Plymouth; as Dorothy Parker said of Hemingway: “He avoided New York because he knew what was good for him.”

What characterised Peryer as an artist was he consistently produced fresh and surprising images that were simultaneously – but only then, and obviously - “Peryers”. And like all significant artists long-term he extended our experience of the world’s unperceived parameters, not only visually but emotionally and intellectually. He consistently queried the gap between realism and the real, a task that photography itself is uniquely positioned to both investigate and illuminate. The often brazen ordinariness of his subject matter – birds in a cage, tree-stumps on a hillside, a fish hauled out of a lake, seed pods, even a portrait like Michael Dunn’s where the physiognomy seems determined to give a passing impression of the surface of the moon – points to something else that only photography can do: to hijack a physical detail about which little, or, more often, nothing is assumed, turning its apparent banality into an often unsettling mediation about the nature of perception and our relationship with the world. As such, Peryer’s images function as small depth-charges, demolishing complacency.

His own lively and independent mind was key to his own dismissal of assumptions, both aesthetic and technical. He burst onto the photographic scene in the mid-’70s with his cocking a snook at both camera equipment and fine printing techniques, taking up the Diana1 camera and often submitting prints of “the same” subject matter where the sequence of images covered almost the entire spectrum of light and shade – although, at least emotionally, the shades tended to dominate in those early days. Not long after, he ditched this moody pictorialism – later calling it his “Moody Blues” look – for the stylistic tricks of the New Objectivity movement (as no contemporary New Zealand photographer has ever done) but gradually made it his own through a combination of quirky subject matter and his central, motivating fascinations with scale and the gap between realism and the real.

Again, when the analogue approach became threatened by the digital revolution, Peryer, unfazed, immediately began investigating its possibilities, and he also embraced colour early, at a time when working in black and white was still assumed to be the sign of a really serious photographer. His uptake of what the smart-phone might do is legendary. Perhaps there’s a connection between this freedom and a certain maturity, because the only other photographer here motivated similarly and so early on these counts has been Gary Blackman, way before many photographers found seduction in instagram.

Peter was his own man and never felt the need to sign up to either schools or styles, making him hard to place by curators and dealers (being placed is a significant element in establishing reputations and moving product), and he demystified artistic practice through his blogging, which was as engaging, stimulating and as unpredictable as his imagery, and he viewed his blog unashamedly as part of his artistic practice. As with Conor Clarke’s, it illuminates the general context and approach rather than attempting to explain specific photographs.

His secure sense of self and independent view guaranteed his being an excellent and very illuminating interview subject. One of the best is by art writer Megan Dunn2 at the time of his A Careful Eye, a sort of-survey show at the Dowse. By the way, recalling this exhibition poses the question: how many photographers of that generation might have their work survive such a radical re-configuration by a curator of a younger generation? Worth considering...

Earlier this year Peryer was interviewed on RNZ’s regular Sunday arts programme Standing Room Only3. During the conversation the topic of portraiture arose, and in attempting to illustrate his perhaps unusual position, Peter used the example of the Oberammergau Passion Play, a longstanding tourist attraction, since 1634, in the small Bavarian town, reconstructing on the stage the final episodes of Christ’s life. Peter said his own portraiture was, basically, a search for faces which might have a part in his own Passion Play. He was once approached to make a portrait of the Dalai Lama on a forthcoming visit here, but despite his admiration for this eminent man he declined the offer on the simple grounds that “He didn’t have a part.”

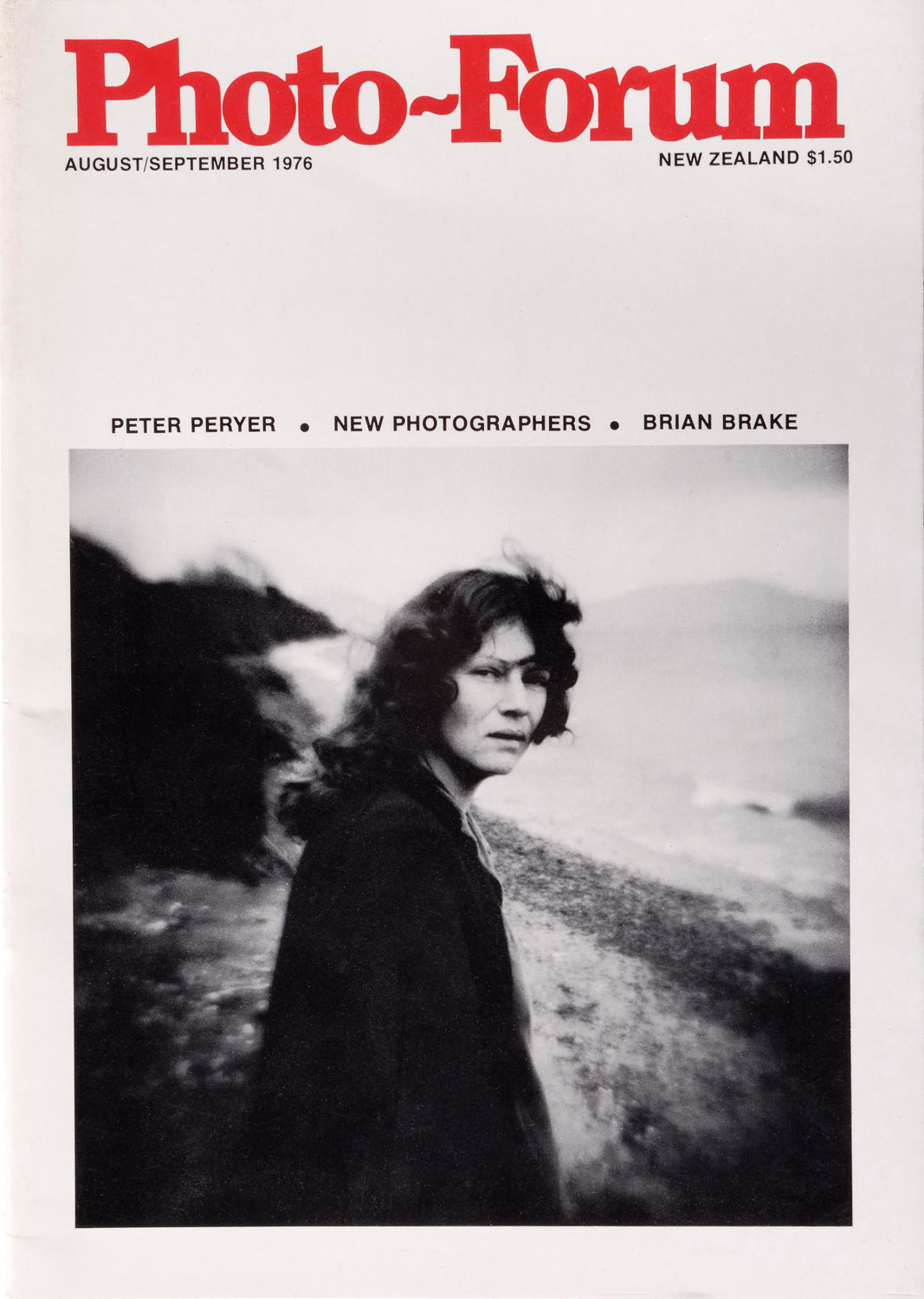

Obituaries seem appropriate for personal recollections. I first met Peter in 1976 at a Snaps4 opening of his photographs – the prints were $35 – and thereafter many times, always in relation to his work, and I feel privileged, and blessed, to have seen it gradually unfold over the past forty years, each image extending the Peryer oeuvre into a vast, inter-connecting visual whanau, the new refreshing the old in always unexpected ways. He was a magician all right, but a conjurer of the solid.

In my few decades of curating it was always a special pleasure to include Peter’s work in exhibitions, and he was invariably agreeable, courteous and thoroughly professional in all matters and never missed a deadline. In terms of writing about his work – always a testing challenge – it was an honour to introduce readers of Art New Zealand to his work in 19845, still a time when art consumers generally remained dubious about the medium. (At this point I can hear Peter laughing and asking “Is it any different now?”)

Critical writing is one of the least successful ways of making friends, so I remain grateful for Peter’s oft-expressed support and encouragement. The last time we met was 18 months ago at a Mark Adams opening at Auckland’s Two Rooms, and he was still chuckling over my otherwise fairly badly-received Art New Zealand piece6 on the Christchurch Art Gallery’s recent photography group show The Devil’s Blind Spot, even quoting various phrases verbatim. I was very touched by his response, and still am.

Peryer may have left us, but what an inexhaustible trove remains. As Horace said: “Life is short but art is long.” Goodbye Peter, we are all in your debt.

Peter Ireland, December 2018

1 The Diana camera was a plastic camera widely considered a toy, available in the 1960s and early 1970s.

2 NZ Listener 23 August 2014 https://www.megandunn.org/2014/08/23/a-careful-eye-peter-peryer/

3 RNZ National, 27 May, https://www.radionz.co.nz/national/programmes/standing-room-only/audio/2018646702/peter-peryer-s-trip-into-the-past

4 Snaps – A Photographer’s Gallery operated in Auckland from 1975 to 1981.

5 Peter Peryer - The Significance of Repetition. Art New Zealand No.31

6 Punting on the Avon: Ongoing Strategies at Christchurch Art Gallery. Art New Zealand No.161

For further reading about Peter Peryer, see our earlier post here.