The roundness of life: Domestic spaces and photography in Aotearoa New Zealand - essay

Featuring: Louisa Afoa, Samantha Matthews, Caroline McQuarrie, Robina Nichol, Marie Shannon and Tia Huia Ranginui

Essay by Christine McFetridge for PhotoForum 2019

Suddenly we find ourselves entirely in the roundness of this being, we live in the roundness of life […].

Gaston Bachelard [1]

When I imagine stanzas, when I think of their rooms, I see them, visually, from above, looking down: a blueprint of a house.

Quinn Latimer [2]

Every line in every poem is the orphaned caption of a lost photograph.

Teju Cole [3]

Think about a structure. Perhaps it’s a house – a bungalow or villa – or maybe an apartment or whare. It needs to be somewhere you feel safe. Can you recall the patterns and textures that hold the walls up; the sounds of activity within these walls? (Without structure, writes Rachel Cusk, events are unreal.[4]) This place, whatever it may look like, is where we conduct our lives, and it’s been a subject for many photographic artists both in Aotearoa New Zealand and abroad.

In The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard suggests that the home fosters thoughts, memories and dreams. [5] At its best, this is what a domestic space can do, especially when shared with loved ones who contribute to our sense of well-being. In the text, Bachelard also refers to the ‘poetic image’; an appropriate coupling of words. Stanza, meaning in English the verse of a poem, translates from Italian to English as both ‘room’ and ‘camera’.

That photography and poetry share similar qualities is something I’ve felt for many years. Both are visual – one more literally than the other – and each convey ideas through metaphor, narrative and representation. And whether words contained by the shape of a stanza, or an image by its frame; when successful, each medium hints at life beyond its form.

Domestic spaces do this, too. My room – where I write this – is tiny and old. There are artworks, books and family photographs nearby. I face a large floor-to-ceiling window and when the weather’s nice, I can leave the door open for Scout to find a patch of sun to sleep in under the ivy. It’s always open enough to hear birdsong, traffic and, during the week, the bell of the school next door.

Famously, Virginia Woolf wrote of the necessity of a room of one’s own; to have the habit of freedom and the courage to write exactly what we think. [6] The rooms that follow, here, are lived in by women whose work demonstrates the importance of our interior lives; their experiences, and the experiences of others, within these spaces; and the effects of colonisation, still visible through furnishings and objects. There’s no time to waste. Let’s go; through another scene, another room, another stanza.[7]

1.

This room is nearly anonymous. A collection of domestic, colonial objects crowd the frame under fog, either the fault of the emulsion or an indication of neglect over time. With the exception of the flowers, there’s nothing in this image to suggest that it was taken in Aotearoa New Zealand. From the National Library collection, it’s only attributed to Robina Nichol. There are a series of images like this one: portraits of interior spaces, which are, more likely, portraits of the people who lived here.

Robina Nichol, Interior with hebe, primula, daffodils on dresser, dry plate negative, c. 1895-1916. Courtesy of the National Library.

The dry plate process afforded early photographers (mostly men) the ability to choose their subject matter. Unlike wet collodion, which allows only a small amount of time between preparing the plate and developing it – to the extent that having a darkroom nearby is necessary – dry plates could be stored for use as the photographer wished. So, Nichol, if it was her (and I write with the assumption that it was), had time to create her own floral arrangements for the image. This action, reminds me of Sara Ahmed’s words:

If we think of the second-wave feminist motto “the personal is political”, we can think of feminism as happening in the very places that have historically been bracketed as not political: in domestic arrangements, at home, every room of the house can become a feminist room, in who does what where, as well as on the street, in parliament, at the university. Feminism is wherever feminism needs to be. Feminism needs to be everywhere.[8]

With this in mind, let’s return to our exploration of the house; there are other rooms for us to get to. [9]

2.

Samantha Matthews, Staircase, from the series Lambhill, digital photograph, 2016. Courtesy of the artist.

From one colonial interior, to another. Follow the faded wallpaper around the corner of the door to the stairwell. Though the pictures that ascend the stairs are new, they would have at one time represented members of Samantha Matthews’s family. Peter Ireland describes her series Lambhill (2016) as something akin to the geologist’s task: a gentle peeling away of layers, not of soil and rock but of history and human occupation, and hers is from the ground up.[10] However, unlike a geologist, it is Matthews’s subjectivity that compels her audience to look carefully.

The homestead, near Fordell, was first built in 1856. Nearly thirty years later, the property was rebuilt before it was sold to Matthews’s great-great grandfather Nathaniel Sutherland. Though she never lived here herself, the house featured significantly in her life; visible from most areas of her parents’ farm. Matthews writes that the house:

sits comfortably in the rural landscape just like the old hawthorn tree hedges that still line parts of the lanes and fences of the land. The trees now permanently bent in the prevailing westerly wind are slowly making their way closer to the earth, but the house still stands. [11]

At the time the series was made, the house was owned by a new family who had preserved it as Matthews had always known it. Though there is dissonance between her memories, real and imagined, [12] and the present, the photographs are intimate portraits of a time which is, in some places, coming away from the walls as if the house were shedding its skin. Yet tangible traces remain: bed linen (so present in the next room), drawings and maps to name a few. A careful imaging of personal history and decay.

3.

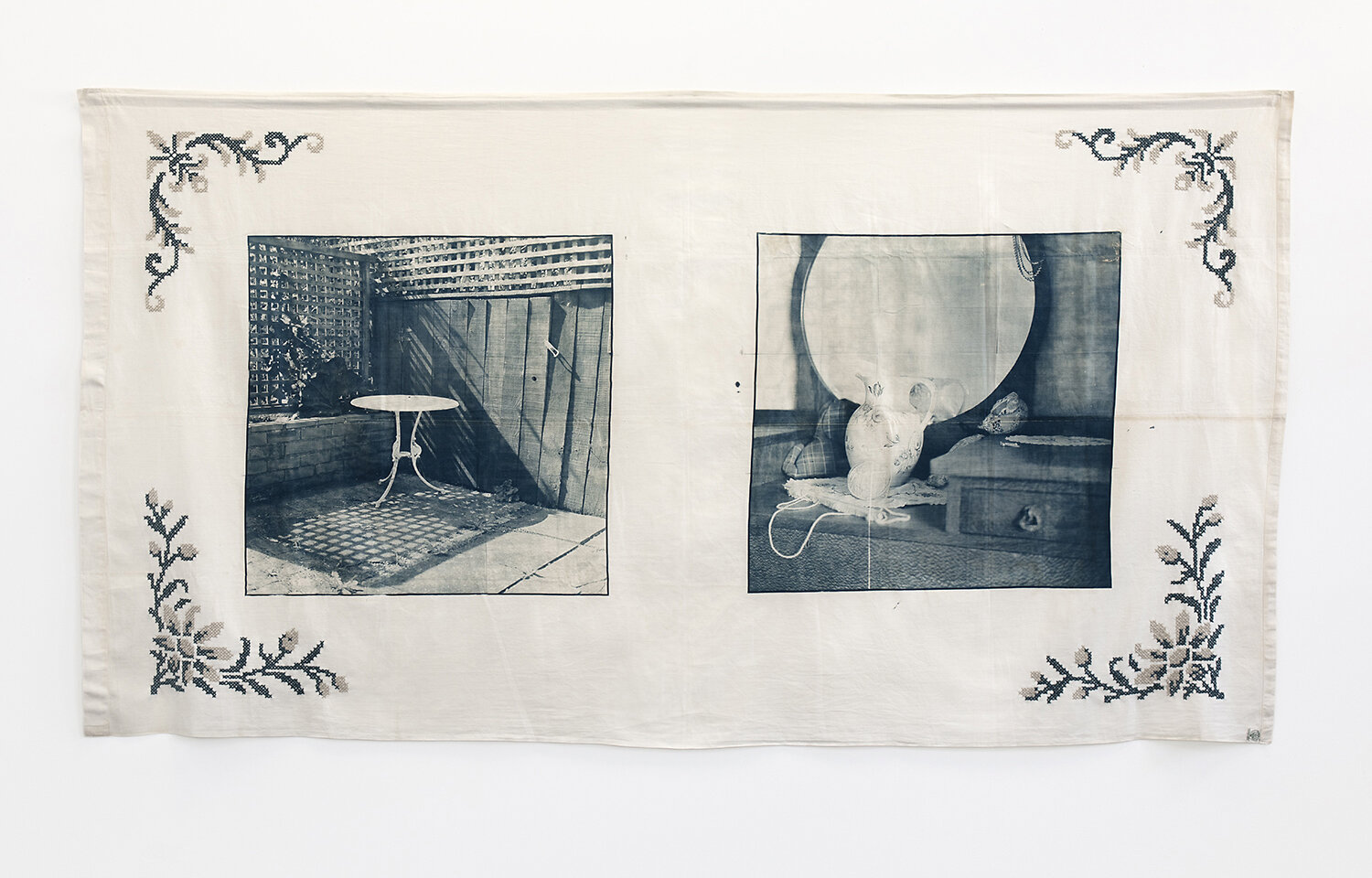

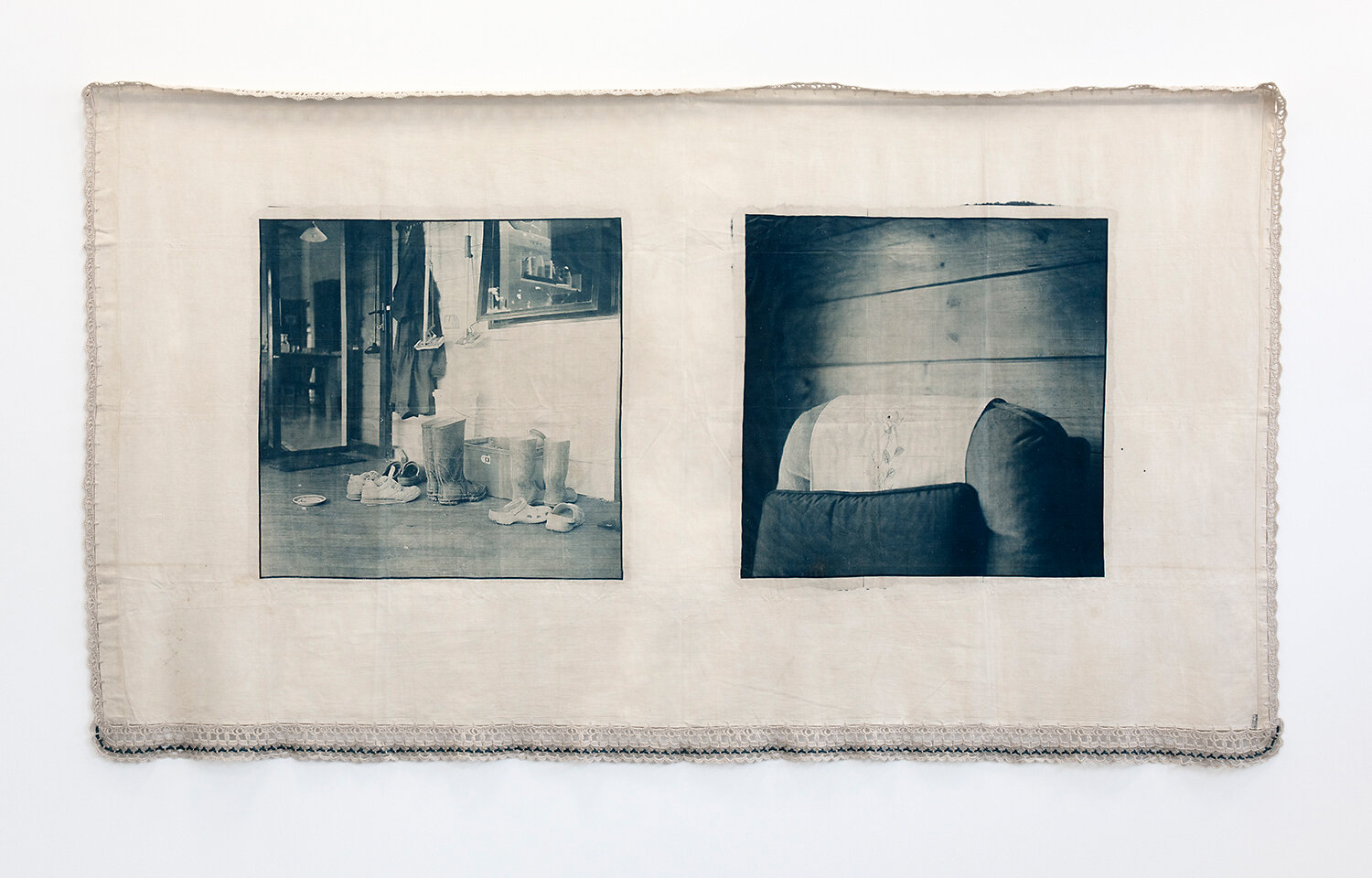

Looking at Caroline McQuarrie’s series Reasons For Silence (2010), I can’t help but imagine the feel of starch against my skin, the cross-hatched edging of the bed sheets; perhaps once softened by the hot press of an iron (my grandmother ironed all of her linen). The materials, made decades before her interventions, have been sourced from op-shops, rather than antiques stores, because of their sense of democracy. And yet, though once precious family objects, these sheets have been discarded (for whatever reason).

Made during the Wellington Star Mercedes Benz Artist-in-Residence at Samuel Marsden Collegiate School in Karori, Wellington, McQuarrie sought quiet, rejecting the noise that accompanies day-to-day life – a noise which only seems to be getting louder and louder.

The photographs, sourced from a large repository, were created by McQuarrie while spending time with family and friends. But, in the way that the processes used speak to what has gone before, the images reject contemporary objects favouring instead ambiguity about time and place. She says:

They’re domestic or suburban moments – just after people have left, or before they’ve come, each image is a pause in between.[13]

The embroidery and crochet on Reasons For Silence i and ii, is a gesture of respect towards Western women’s creative practices, and its emotional labour and value. In conversation with Deidra Sullivan, McQuarrie explains: I’m interested in the women who made [these objects] partially because they wanted to make something beautiful for their families but also because they wanted to do something creative. [14] Thus, the entire process of making these works, from exposure to the final knot in the thread, is hands-on. McQuarrie’s last gesture emphasises the domestic; the works are toned using tea bags.

4.

From the interior, to the exterior; the individual, to the community. And like so many photographs, the visual elements within this photograph are tied to experiences outside of it (some of which are not mine to tell).

Tia Huia Ranginui, Wealth, from the series The Intellectual Wealth of the Savage Mind, digital photograph, 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

Tia Huia Ranginui (Ngāti Hineoneone) subverts the ways Māori have been (mis)represented in art and imagery post colonisation. In an interview with Vice, she says:

Art is a vital part of keeping matauranga Māori alive, to promote a Māori worldview where Pākehā views usually dominate, prevail in the art world. I see it as an intrinsic part of our culture, within all of us, that we can use to work through our feelings and heal from the colonial history of our people and land, to turn something very sad into something constructive.[15]

Part of a larger series, The Intellectual Wealth of the Savage Mind (2015), the image was created at Ranginui’s marae Ātene, Te Rangi-i-heke-iho, situated near the Whānganui River. Named Ātene (Athens) in the nineteenth century by missionary Richard Taylor, the marae was a safe place for Ranginui. Her late father had a hand in restoring the decorative elements present in this wharepuni: he laid the native timber parquet floor and painted the kōwhaiwhai that line the rafters.

Our figure, set between a pile of patterned mattresses, is just one of the many people who would have slept here over the years. Except their arm is hanging down, perhaps in resignation, so that while this is a place of comfort, it is also a place that remembers the weight of its history.

5.

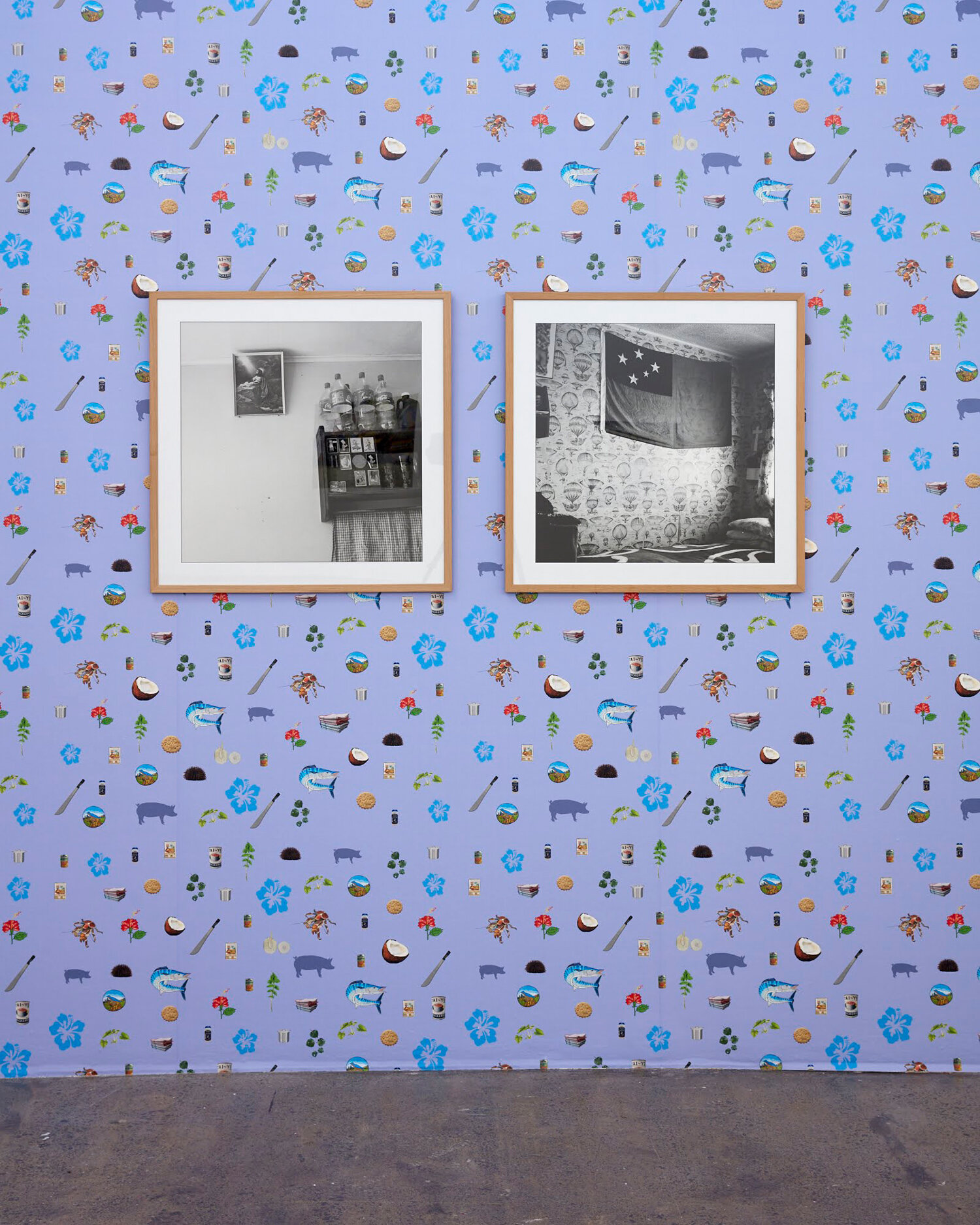

Like the last, our next room is a family room – filled with stories told since forever. Though the tradition of storytelling may differ between families, its function is the same: to make sure we remember. Louisa Afoa’s wallpaper installations are just that; a visual representation of her family’s oral history.

After creating earlier text works that referenced this tradition, she wanted to develop work that felt celebratory and was an ode to the space that fostered [her] understanding of what it meant to be Samoan. [16] Sometimes this space is private; a way of acknowledging the relationships and shared histories that make us. The outside world doesn’t always need to know. She says:

I like that the wallpaper's kind of everyday and mundane and nothing, but at the same time, to me, it's everything.[17]

I’ll see you at Orion (installed at Corban Estate Arts Centre, 2017) is a love letter to Afoa’s great-aunt and uncle, who settled in Orion Street, Papakura, from Samoa in the 1950s. The work is influenced by the wallpaper in this home, and by the people who lived there. Afoa’s great-aunt, the family matriarch, also supported her father to migrate to Aotearoa New Zealand twenty years later. In this way, two histories – and experiences of different countries – become part of the same story.

At Artspace, we meet the framed photographs The Kitchen (2011) and Ruebens Room (2011) again; it’s like returning home. This installation, Kai as Koha (2019), which included work by Cora-Allan Wickliffe and the BC Collective, illustrates indigenous or culturally significant animals, food and objects; each determined following conversations and shared stories between Afoa and her family and friends. She asks us to consider what is important to us. What do we need to remember?

6.

Family room to family room to family room. Over her career of more than thirty years, Marie Shannon’s work has been largely concerned with domestic spaces; her own:

I am one of those people that really likes sitting in a room staring at a corner – looking at the space of a room, at the arrangement of furniture. Locations have their own characters but there is something universal about domestic locations. It’s a background against which you can do things and say things. [18]

The first time I saw The Rooms in the House (2016) was in Shannon’s survey exhibition Rooms Found Only in the Home in Christchurch – my actual home and for all the complex feelings I have about the place (but, maybe, that’s an understandable assessment of a place you grow up in) it still feels like home – the gallery space so familiar.

Marie Shannon, still from The Rooms of the House, digital video 15.53 minutes, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and Trish Clark Gallery.

The video, composed entirely of text vignettes, allows her to create the pictures she isn’t able to take with her camera.[19] Instead, the viewer must create associations in their mind; in the same way that Shannon’s conversation with her son Leo leads them from one memory to another.

When Leo was born, Shannon writes, I started seeing the objects in our house in a new way. [20] When he leaves home temporarily, they chronicle what he remembers of their house over a series of Skype conversations; her thoughts and questions in white, his recollections a softened red that’s not quite pink or brown. Together they remember Julian Dashper, Shannon’s partner and Leo’s father, and shared experiences, gestures and objects.

When, in 2016, Shannon visited Leo in Amsterdam, she asks him for a final thought about the house; if it can be summed up:

He says no. He doesn’t feel that he’s left the house permanently, so he doesn’t have that kind of distance. [21]

The words appear and just as quickly, fall away. Each stanza a room. Bachelard said the poet speaks on the threshold of being. [22] Stepping outside, you close the door behind you. Gently now.

Christine McFetridge is a photographer and writer represented by M.33, Melbourne. She is currently an MFA by Research candidate at RMIT University and a founding member of Women in Photography NZ & AU.

Footnotes

[1] Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, Translated by Maria Jolas (Beacon Press: Boston), 1969, p. 234.

[2] Quinn Latimer, 'Interiors: Some Stanzas on the Pleasures of Privacy' in Like a Woman: Essays, Readings, Poems (Sternberg Press: Berlin, 2017), p. 103.

[3] Teju Cole, ‘Teju Cole: Blind Spot’, The Wheeler Centre, accessed September 17, 2019, https://www.wheelercentre.com/broadcasts/teju-cole-blind-spot.

[4] Rachel Cusk, Outline (Faber & Faber: London, 2014), p. 24.

[5] Bachelard, p. 6.

[6] Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own, (Penguin: London, 1945) p. 75.

[7] Latimer, p. 106.

[8] Sara Ahmed, Living a Feminist Life (Duke University Press: London, 2017), pp. 3-4.

[9] Latimer, p. 107.

[10] Peter Ireland, ‘Worn & Torn’, Eye Contact, September 16, 2016, accessed September 10, 2019, http://eyecontactsite.com/2016/09/worn.

[11] Samantha Matthews, ‘Lambhill’, artist’s website, accessed July 26, 2019, https://samanthamatthews.co.nz/lambhill.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Caroline McQuarrie, ‘Reasons For Silence’, wall text from Reasons For Silence (Toi Pōneke Gallery: Wellington, October 29 – November 20, 2010).

[14] Ibid.

[15] Aimée Ralfini, ‘Four New Zealand Artists on Confronting Colonialism’, Vice, February 6, 2018, accessed July 26, 2019, https://www.vice.com/en_au/article/59kzyb/four-new-zealand-artists-on-confronting-colonialism.

[16] Louisa Afoa, email to the author, September 24, 2019.

[17] Murphy, ‘”The emotional labour is too real”: Why artist Louisa Afoa is telling her story on her own terms’, RNZ: The Wireless, October 2, 2017, accessed April 5, 2019, https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/the-wireless/374899/the-emotional-labour-is-too-real-why-artist-louisa-afoa-is-telling-her-story-on-her-own-terms.

[18] Lara Strongman, ‘Marie Shannon talks to Lara Strongman’, Bulletin, accessed September 10, 2019, https://christchurchartgallery.org.nz/bulletin/193/marie-shannon-talks-to-lara-strongman.

[19] Mary-Jane Duffy, ‘Marie Shannon reviewed – May 2018’, PhotoForum, accessed September 10, 2019, https://www.photoforum-nz.org/blog/2018/5/14/h00fcfrkggivjwqqboawxw82tkyjhz.

[20] Marie Shannon, The Rooms in the House, 2016. Digital video, 15:53 minutes.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Bachelard, p. xxi.

Slideshow captions for mobile devices

Caroline McQuarrie

Caroline McQuarrie, Reasons For Silence (i), from the series Reasons For Silence, cyanotype and wool embroidery on vintage cotton bed sheet, 2010. Courtesy of the artist

Caroline McQuarrie, Reasons For Silence (ii), from the series Reasons For Silence, cyanotype and wool embroidery on vintage cotton bed sheet, 2010. Courtesy of the artist

Louisa Afoa

3. Louisa Afoa, The Kitchen, digital photograph, 2011; Ruebens Room, digital photograph, 2011; and Orion, digitally printed wallpaper, 2017. Exhibited at Corban Estate. Photograph: Artsdiary. Courtesy of the artist.

4. Louisa Afoa, The Kitchen, digital photograph, 2011; Ruebens Room, digital photograph, 2011; and Untitled, ‘Kai as Koha’, digitally printed wallpaper, 2019. Exhibited at Artspace. Photograph: Sam Hartnett. Courtesy of the artist.