Live from the Moon - reviewed

Live from the Moon

Curated by Geoffrey Batchen

Suite Gallery, Wellington

4 – 26 May 2019

Reviewed by Emil McAvoy for PhotoForum, May 2019

Associated Wire Press Photo (USA), Mrs Edgar Mitchell reaches out to ‘touch’ her husband on the moon. 5 February 1971. Collection of Justine Varga, Sydney.

Live from the Moon comprised a selection of NASA's 1960s and '70s press photographs depicting their efforts to land men on the moon,[1] curated by acclaimed photography historian Geoffrey Batchen from his personal collection.[2] The exhibition was presented at Suite Gallery, Wellington, as part of the Photival photography festival.[3] It was also timed to align with the 50th Anniversary of the Apollo Programme, and in particular, the Apollo 11 lunar landing on July 20, 1969. Humankind first setting foot on the moon: one small step...one giant leap...et cetera.

In part, Live from the Moon also echoed Dark Sky, an exhibition Batchen co-curated with Adam Art Gallery Director Christina Barton, which featured an ambitious group of New Zealand and international artists who have explored how photography has been deployed to capture the skies. Dark Sky was timed to align with the Transit of Venus in 2012.[4]

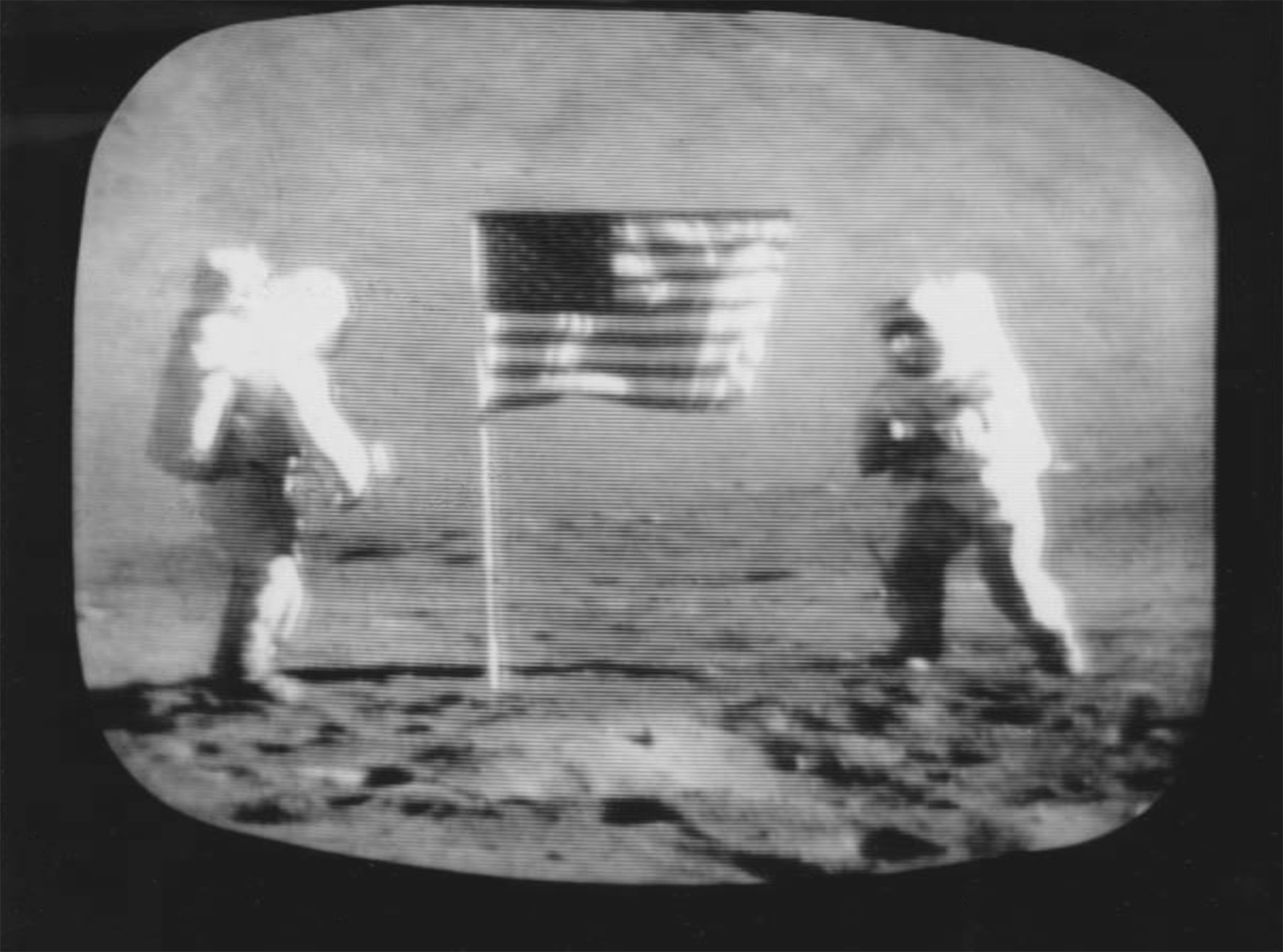

The Live from the Moon exhibition catalogue notes that these NASA images were sometimes shot with video cameras and automatically transmitted to Earth as radio signals from spacecraft. They were then reconstituted by computers in the form of photographs and distributed to the press via the electric telegraph. On other occasions, photographs would be taken of images seen on television monitors while these were being broadcast to Earth in real time. More rarely, the photographs were taken with hand-held cameras by astronauts from the windows of their space capsules.[5] NASA's early rockets were fitted with cameras and designed to crash land in to the moon, filming and broadcasting until they hit the surface – image streams characterised by their culmination in static.

NASA (USA), AP Wirephoto, First Picture of the Moon: This was one of the first pictures of the moon made by Ranger 7 released tonight at Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. Picture shows numerous craters on the surface of the moon which hitherto had not been detected by earth-bound telescopes. 31 July 1964. Collection of Geoffrey Batchen, Wellington.

In a public discussion at the gallery, Batchen spoke to how these particular images evoke "the truth value of photographs", and that they "bear the rhetorical promise of all photographs" – a certification of the real.[6] Given these gelatin silver photographs had been sent out as press prints by NASA, they bear a certain truth value predicated on the scientific esteem of their producer. Yet conversely, they are often visually ambiguous – "hovering between abstractions and documents"[7] – and rely on their extensive captioning to provide explanation and context.[8]

Batchen foregrounds, "what I like about the selection that I've been making here, from the thousands available on eBay, is a lot of these ones hover between your willingness to trust and your ability to verify that trust – in looking, actually looking, at what you see. They are strangely in between kind of objects and images – they're odd."[9] These images are rendered in grainy greyscale, sometimes in soft focus and overlaid with a grid, noisy due to their early digital transmission, and at times distorted by being photographed from a television screen during live broadcast. Space oddities, then, which demand a reflective and questioning encounter.

Associated Wire Press Photo (USA), After unfurling the American flag, the astronauts photographed each other. Cernan (right) got set to snap a picture of Schmitt. 12 December 1972. Collection of Geoffrey Batchen, Wellington.

The exhibition's chronological hang concludes with a 1972 image from Apollo 17 in which, after unfurling the American flag on the surface of the moon, Commander Eugene Cernan snaps a photograph of Lunar Module Pilot Harrison Schmitt. Batchen notes, "Cernan and Schmitt spent just over three days on the moon in the Taurus-Littrow valley and completed three moonwalks, collecting lunar samples, deploying scientific instruments, and taking photographs. A detailed mission timeline prescribed exactly when and where photographs were to be made."[10] In this case, replicating a kind of family snapshot.[11] An explorative scientific mission concurrently framed by a highly stage-managed process designed to produce widely consumable images – images as evidence, and as justification for the space programme's tremendous financial cost.

The machinations of the Cold War underscore these images, particularly the development of the American satellite programme to monitor and verify Russia's claims as to the quantity of their atomic weapons. Hence, in this context, these images of the moon were both a source of pioneering scientific value, and strategically syndicated as American propaganda and publicity in order to claim superiority in the realm of technological advancement. Technology developed by the military industrial complex which could be easily deployed in war.

NASA (USA), Associated Wire Press Photo: Target for Surveyor 7: Mountainous area around the crater Tycho, one of the roughest spots on the moon (taken by the Lunar Orbiter V spacecraft). August 1967. Collection of Justine Varga, Sydney.

Though we find ourselves in a new age where space exploration is increasingly privatised – (Lockheed Martin, SpaceX, Rocket Lab, .et cetera) and other nation states and robotic technologies have also come to the fore – little appears to have fundamentally changed in that regard, including the uses to which photographic technologies can be put to. On the other hand, the vast realms of unexplored space retain mysteries beyond our ability to comprehend, let alone co-opt them. With the advent of new images generated by technologies like radio telescope arrays – the first 'photograph' of a black hole, for example – there is a whole new frontier upon us which makes the unseen visible. And, however, close in relative proximity, the moon still occupies a certain poetic space in the public imagination.

Batchen notes, "tracing a history of human efforts to venture into space, these photographs also offer an important staging point in the development of digital imaging and therefore in the history of photography itself."[12]

Having been emailed the exhibition catalogue as a digital file prior to my visit, after flying to Wellington to see the prints, when present in the gallery I remember feeling for a moment that – in light of my digital material – I hadn't actually needed to make the trip. This is no slight on the exhibition. Rather, it was an ironic reflection on their ongoing mediation and shifting modes of electronic transmission: from early digital technologies (sent as data via radio bursts and reconstructed by computer), to their circulation by the press via electric wire transfer and mass reproduction print technologies; and more recently, being released by press archives for sale, to their current proliferation as digital image files on sites like eBay. It was, however, rewarding to see the scale of these prints in the flesh: their details, glossy sheen and the odd faint ding in their surface, evidence from lives well lived. Given the numbers of prints in circulation, and available for as little as USD$10 each plus postage, there appears to be plenty of life in them yet.

City Gallery Wellington's concurrent exhibition The Technological Sublime by the UK artist duo Semiconductor also offers some compelling connections to Live from the Moon. Several large video projection works source, sonify and visualise volumes of unprocessed raw data from key scientific institutions to interpret contemporary space exploration. The immersive visual scale of Brilliant Noise (2006)[13] and Black Rain (2008)[14] – and their rumbling, glitchy, crackling, hissing soundtracks – communicate a sense of the awe alluded to in the exhibition title.

Semiconductor, Black Rain, 2008, The Technological Sublime. (Image, courtesy City Gallery)

While both exhibitions centre on making scientific data visible, Batchen asserts that the difference is that photographs of the moon are grounded in a very real political and cultural context: there is something at stake in their making.[15] On the other hand, City Gallery Chief Curator Robert Leonard states, "while celebrating the artistic capacity of scientific imaging technologies to serve up a new brand of sublime, Semiconductor also invite us to consider what might be at stake in our easy seduction."[16] And while NASA made a recent and significant announcement that it is returning to the moon – to stay – Batchen's co-presenter at their gallery talk, Haritina Mogoșanu, put it well: "the moon is a very political environment."[17]

Emil McAvoy is an artist, art writer and lecturer in Photo Media at Whitecliffe College of Arts and Design.

[1] I use the term "men" here to refer to the common parlance of the time, further echoed in the media release text for this exhibition, and is in no way intended to downplay the prominent role of women in space exploration, both past and present.

[2] Batchen is Professor of Art History at Victoria University of Wellington. His books include Burning with Desire: The Conception of Photography (1997), and Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph (2016). His most recent exhibition was co-curated with Deidra Sullivan in 2018 for the Adam Art Gallery and titled Still Looking: Peter McLeavey and the Last Photograph. Live from the Moon also includes photographs from Justine Varga's collection.

[3] The festival describes the exhibition as giving "an insight into the circular influences that humanity and technology have on each other. Technology enables us to view ourselves and our planet in new exciting ways and allows us to analyse our behaviours and interactions with each other and the universe."

[4] Dark Sky, Adam Art Gallery, Wellington, May 1 – July 8, 2012, http://www.adamartgallery.org.nz/past-exhibitions/dark-sky/

[5] Geoffrey Batchen, Exhibition Catalogue, Live from the Moon, 3. See also: http://suite.co.nz/live-from-the-moon

[6] Geoffrey Batchen and Haritina Mogoșanu, Senior Science Communicator from Space Place at the Carter Observatory. Moderated by Matthew Plummer, Digital Research Consultant in the Centre for Academic Development at Victoria University of Wellington. May 9, 2019 at Suite Gallery,

http://www.photival.com/partnerevents/2019/5/9/live-from-the-moon-a-conversation

The pair also discuss the exhibition on RNZ, May 5, 2019,

https://www.rnz.co.nz/national/programmes/standing-room-only/audio/2018693646/the-moon-in-closeup-for-the-first-time

[7] Batchen, Exhibition Catalogue.

[8] These captions are hidden by the mattes used in their framing, but reproduced in full in the exhibition catalogue.

[9] Batchen, discussion at Suite Gallery.

[10] Batchen, Exhibition Catalogue.

[11] Batchen, discussion at Suite Gallery.

[12] Batchen, Exhibition Catalogue.

[13] Brilliant Noise mines the data vaults of solar astronomy. Usually cleaned up for public consumption, source images have been left in their glitchy raw state. The disruptive rain of visual noise is enjoyed as another level of information – an index of cosmic rays. The soundtrack is made by translating image intensities in to audio. (From the exhibition wall text, City Gallery Wellington).

[14] Made from images collected by the twin-satellite Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory, Semiconductor collects visual data from its Heliospheric Imager as it tracks interplanetary space for solar wind and coronal mass ejections heading to Earth. Planets, comets, the Milky Way, and more distant stars pass by. (Adapted from exhibition wall text, City Gallery Wellington).

[15] Email to the author, April 28, 2019.

[16] Robert Leonard, introductory wall panel text, City Gallery Wellington.

[17] Haritina Mogoșanu, discussion at Suite Gallery.