The Last Race - featured portfolio

The Last Race

Photographs by Dylan Owen & Sean McMahon

Essay by Max Oettli

PhotoForum featured portfolio, August 2019

Dylan Owen’s photographic practice aligns with the concept of public photography as a medium for civic memory. This includes documenting anything from mass participatory activities like festivals, and protests to vernacular architecture.

Sean McMahon is a Wellington archivist, photographer and a keen horse-racing enthusiast. Currently he is enjoying the challenge of black and white film photography. Visit https://www.instagram.com/sean.jd.mcmahon/ to view more of his work.

The Last Race is a two-pronged research project that aims to preserve thoroughbred horse racing records and photographically document a selection of New Zealand racing clubs, particularly those identified for closure in the 2018 Messara Report which investigated the state of thoroughbred horse racing in New Zealand.

Racing. The sport of kings. Something vaguely along those lines. I felt that my immigrant Swiss parents disapproved of it; Swiss Calvinists who believed in the virtues of hard yakka, the pittance you could gain by this and stack against a dark future of prosperity or misery. Did I mention that my dad dropped dead at 59, heart failure from overwork? Dad, Hans Oettli (Major, Swiss Army) was a fine horseman though.

In Kelly Ana Morey’s beautiful fiction biography of the legendary horse Phar Lap, a few years ago1 she emphasized that a good portion of kiwi household money ended up in that place of loss and beauty, the racetrack. As I grew older and more depraved, and dropped the Prespy and other terriens for more direct and turfy pleasures I began to realise the need for certain vices, like going to the race track occasionally, with a ten dollar kitty which I was prepared to play off.

To Aotearoa: Dylan Owen and Sean McMahon are obviously onto something with The Last Race which goes beyond mere documentation and empathy with this institution. Apparently, Sean even worked on race tracks in the past, and their familiarity and knowledge of the repeated patterns of racetracks throughout the two islands we live on (is there one on Stewart Island, the Chathams?) is comfortably in evidence in this series. Their project comes at an interesting moment in history.

What Vincent O’Sullivan wrote some years ago is no longer entirely gospel: “How often, the first thing that strikes one on entering a New Zealand town is the smooth attended green of the track, the immaculate white ribbon of the railings, the distinctive structure of the stands, and not infrequently, sheep grazing in the longer grass in the middle of the course (...) the buildings, the grounds, the elegant proportions between curves, straights and double tracks, are features as permanent as town halls, the war memorial, and the churches further along the road.”2 In answer to his rhetorical question, it must be said: not as often as forty years ago, which is no doubt part of the motivation for this new documentation.

There has been photographic work done on horse racing before. Marti Friedlander, Brian Brake, Ans Westra, and the present modest writer all have the classic rendering of the atmosphere as the beasts and their riders thunder down the turf, but as yet another colour on our palette of documents, notes on the country we live in, rather than as a central theme. The definitive book (from which Vincent’s above quote comes) is Glenn Jowitt’s Race Day, a beautiful work by a photographer who died far too young (alas, as did Robin Morrison) and which illustrates the situation that Vincent so lovingly describes. Has there been a decline in following the gee-gees? I have no statistical evidence to hand, and it is possible that the bigger courses soaked up the (apparently) $100 or so by head of population that we place on our winners, runners-up and also-rans. There could be a useful photo essay documenting the poor relations of horse racing, the lotto and pokey machines, but this falls outside our scope for now.

Photography too has changed. What Jowitt learned at Canterbury 3 from Glenn Busch and Larence Shustak as a ritualistic craft, a process, is a dead horse now scarcely worth flogging anymore. The digital revolution has made our field infinitely more accessible and quantitively explode on an exponential curve that would make Virilio pale. I write these lines in a quiet café in Shanghai and at a quick count there are four cameras and about 20 smartphones out in my view. While I drink my rather insipid coffee I see at least 50 photos being taken, from endless giggling selfies to two serious shoots, one an earnest student with his Huawei phone of a girlfriend sporting a new handbag striking the right poses, (there is a story in that) and one of a schoolboy doing closeups of the pattern on his buddy’s sloganned shirt with a DSLR. These photos will never be on paper, may never be seen except on small screens, possibly tablets. They need no enhancement further than those that the apps on the equipment they are shot with provide them with. Phooey to Ansel Adams and his zone system, long live the algorithms of the cellphone system.

We are looking at 25 photos, thematically rather than syntactically related, arranged in a numbered sequence and covering a number of racetracks and situations. I am not overly curious about how the collaboration works, who presses the button where and when. The world is full of collaborative work, where would Beaumont be without Fletcher, Mozart without Da Ponte, Laurel without Hardy? Here, Owen and McMahon choose to credit all their pictures as collaborative.

The first thing that strikes me in this set is the idea of fences, gates, barriers; how the whole structure of the racecourse is one of inclusion and exclusion. Isn’t the members’ zone at racecourses called an “enclosure”? Is that what the picket fence around the tent at Trentham is for?

There is a barrier behind the anti-racing protestors in the opening photo, a barrier with starting gates in the second, white barriers figure large in the various more distant views at Trentham, Rotorua and elsewhere. At Wairoa the wahine on the ground makes a rude sign at her mates, perched in the castle of the stands and protected by a high tin wall. The crowd cheering behind the barrier is priceless, whichever of our twins did this, masters the idea of quick prefocused shots very well. And what moment more decisive but the flashing of the first nose past the post? And that weird TAB shed in Tauherenikau (did I spell that right? Where on earth is it?)4 with the punters peering in through the windows. A technical tour de force in terms of light and colour balance. The final photo shows a finish line which looks like the vestiges of a chapel of a forgotten religion.

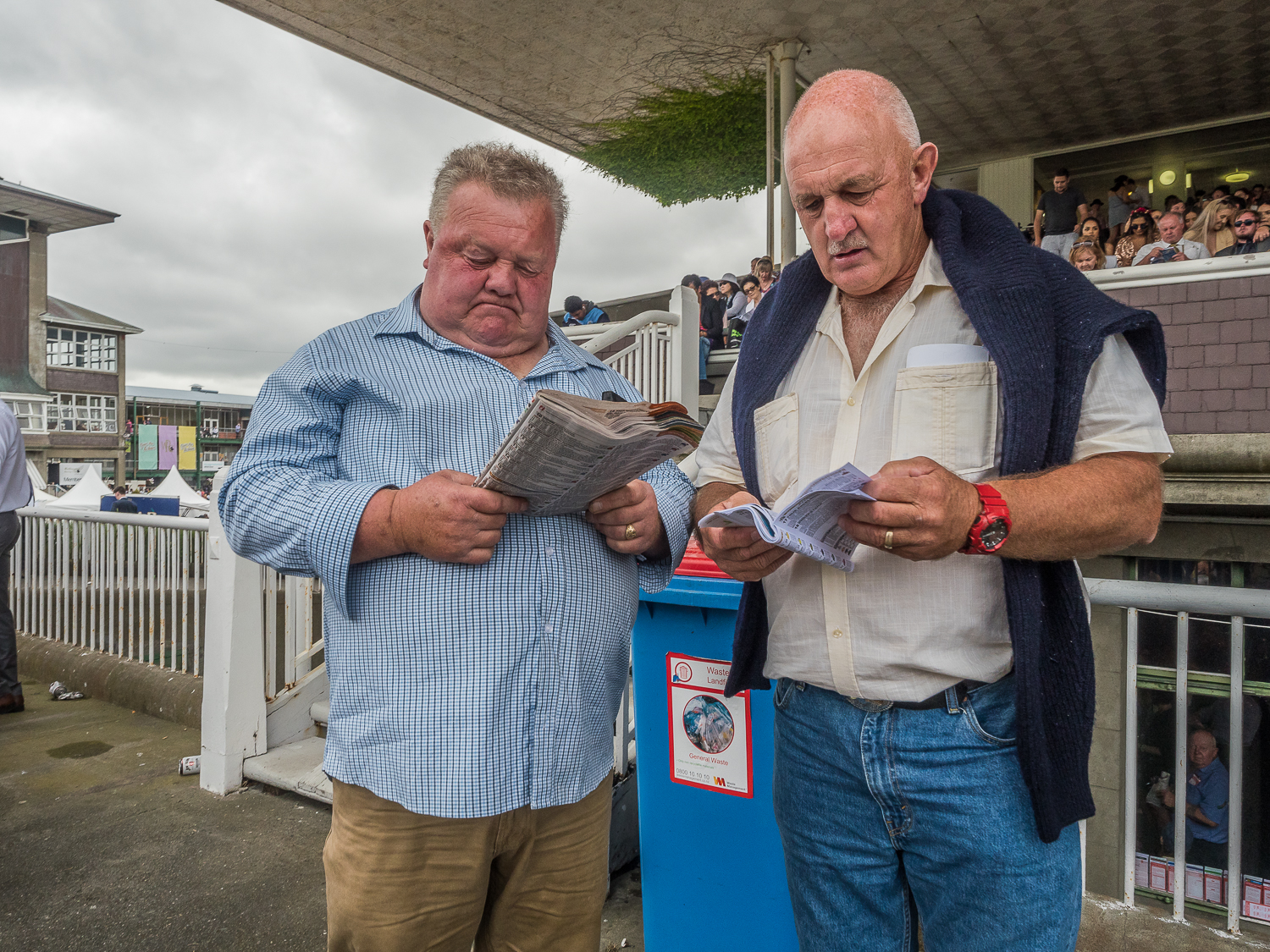

Much here is decayed, like the monstrous totes calculator the size of a locomotive. Imagine it clattering out the results up there in Wairoa, where the local Alan Turing probably cuts T-Bone steaks for a living. The clubroom at Trentham is a tad decrepit, the Bar is closed, the magnificent striped sausage curtain stays rolled up. And the sole occupant is relaxing on a prehistoric comfy chair. Reading, one supposes, the racing page, as are the two mates in an earlier photo.

The architecture also has something of a military (or even prison) camp. Watchtowers abound, big brother is studying form, the distant gate of Trentham along a wet path. The structures range from elegant to functional to seriously rickety. The tower at Dargaville is a joke, a cow cocky’s fantasy, respectfully rendered.

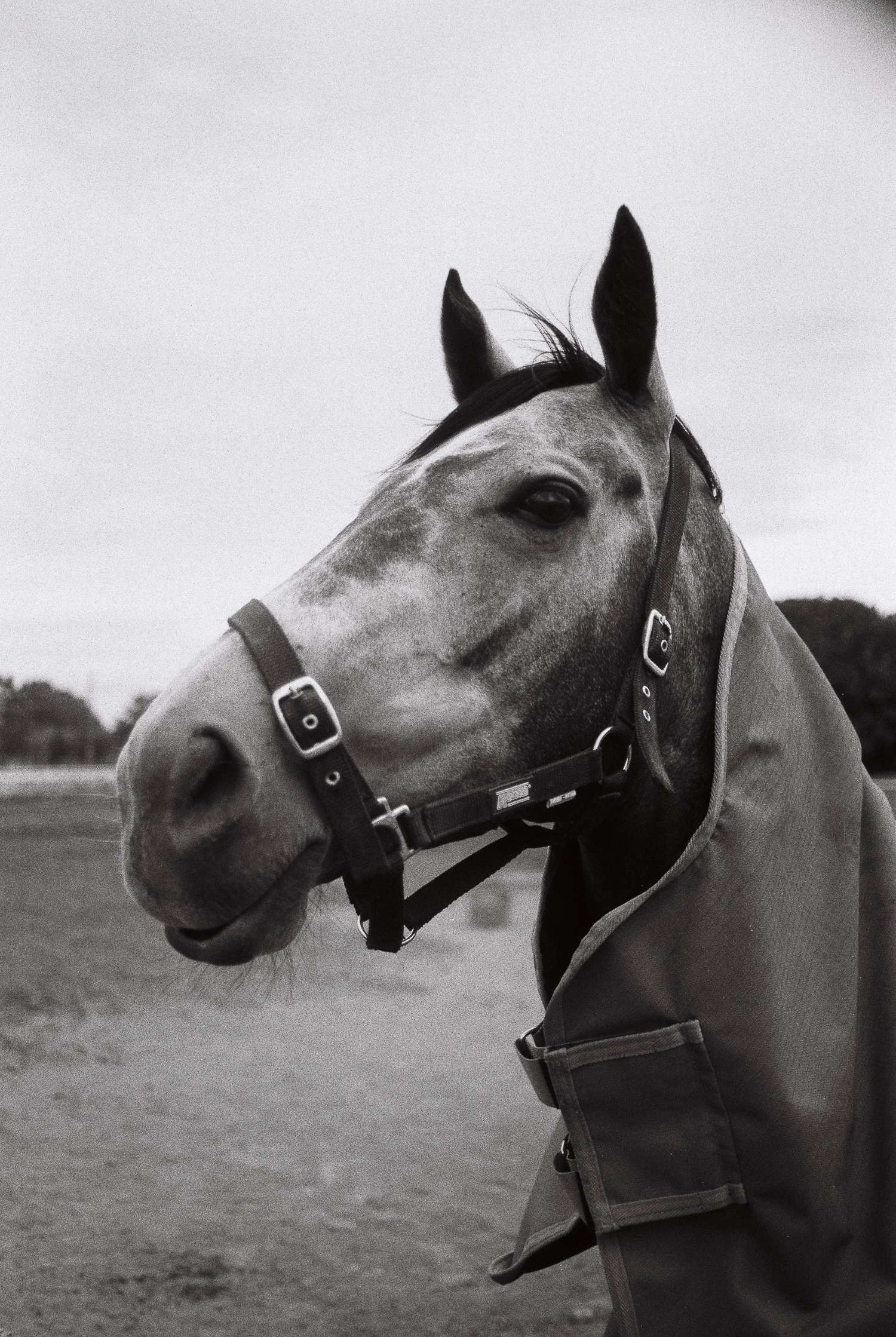

A few pictures that tell us much, often more than initially seen. The farrier is an utterly real example of the first category, straight photography of a good benevolent bloke. I imagine him surrounded by swarms of Mokopuna after a hard day at the anvil.

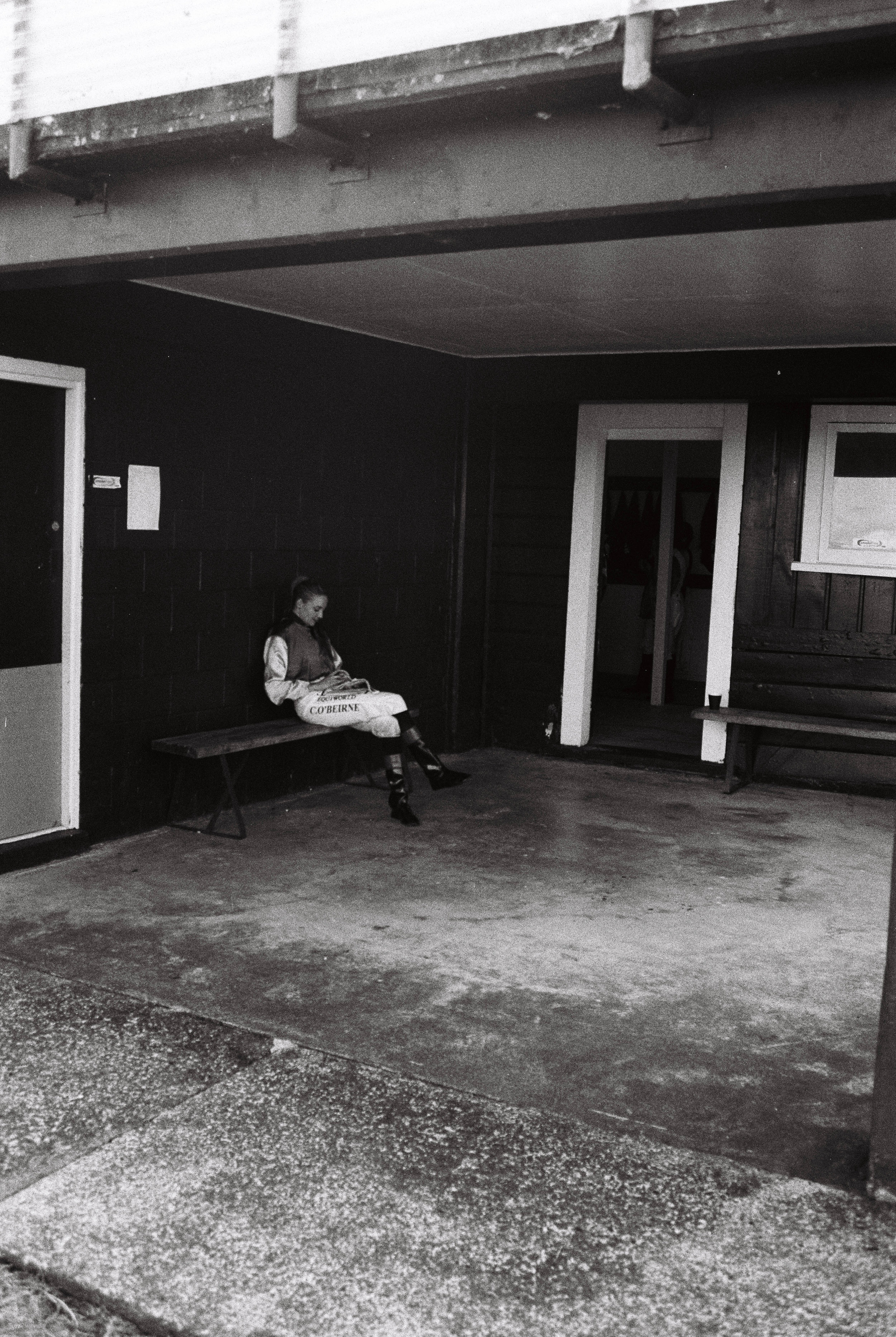

The Jockey on his winner, both breathing in through their mouths goes a little further semiotically. The extra element here is a drone soaring like a malevolent insect above our exhausted pair, a harbinger of our century in an otherwise vaguely obsolete world.

A beautiful and evocative image of a girl’s hair in the foreground delicately mingling with the tail of the passing horse. The punctum as uncle Roland Barthes would say is the horse tat she sports on her back.

A whole other theme or thesis comes up here. For now, we enjoy what we see and feel we are sharing an experience which has been part of our culture for millennia.

Max Oettli

Dardagny, Geneva 30.06.2019

(1) Morey, Kelly Ana. Daylight Second. Auckland: Harper Collins, 2016.

(2) Jowitt, Glenn, O'Sullivan, Vincent. Race Day. Auckland: Collins, 1982

(3) University of Canterbury School of Fine Arts

(4) Between Greytown and Featherston

Born in Switzerland in 1947 and educated at Auckland and Geneva Universities, Max Oettli is a photographer writer, and teacher. His last appointment was as Principal Lecturer, photography at the Dunedin School of Art. He lives between Wellington and Geneva.

Recently he deposited and catalogued his New Zealand photographs 1966-76 at the Alexander Turnbull Library. A major show of his work is in preparation at the Auckland Art Gallery, and he is in two group shows in Wellington from mid June on, at Photospace and at Te Papa (The New Photography).

This essay made with funding from Creative New Zealand.