Auckland Modern: Photographic Works by Steve Rumsey

Steve Rumsey

Charles Ninow Fine Art Dealer

102/203 Karangahape Road, Auckland Central

6 December 2025 - 17 January 2026

Preview: Saturday 6 December 3 - 5pm

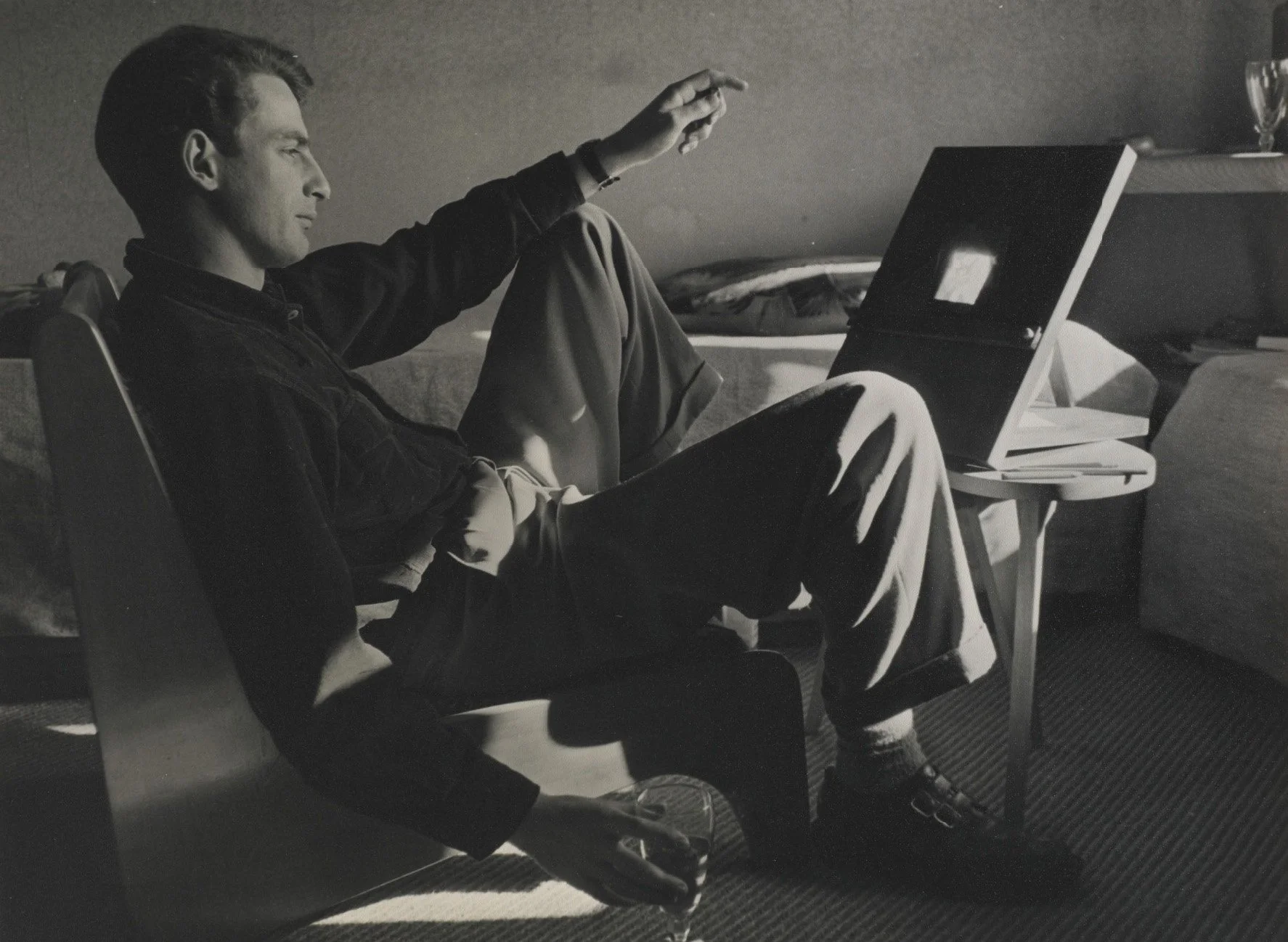

Steve Rumsey, Barry Woods at Retouching Desk, 1953. vintage gelatin silver print

Steve Rumsey’s work is held in our most important museum collections and is an essential inclusion in any serious publication about New Zealand photography. However, for the most part, his practice has sat outside of the cultural gaze. Rumsey started making photographs in the 1940s, well before analogue photography was driven to the height of its cultural relevance in the 1970s and 1980s by a well-educated, well-resourced baby boomer generation. This later era produced PhotoForum, an influential journal founded and edited by John B. Turner, which ran for a decade. It also produced artists like Peter Peryer and Laurence Aberhart, who are rightly regarded as two of the most significant figures in New Zealand photography.

The PhotoForum era championed practices that were both poetic and technically proficient. This approach was akin to the musicians producing the guitar-driven soundtrack of that era. By contrast, Rumsey’s output was methodical and deliberate. If his images contained any personal content, it required explanation to be understood. His images exist as tools for the world, relying on nothing external to the image to function. Speaking of his practice in the 1940s and ’50s, Rumsey stated that he ‘wanted to establish a means of making [photographic] images without chance being a major factor in the process.’ He also described his works as ‘conceptual’, though not in the common art-historical sense where the idea supersedes aesthetic qualities. In Rumsey’s practice, the idea always preceded the image, even if execution relied on encountering the right circumstances in the field.

The development of Rumsey’s aesthetic sensibilities began in the 1930s when he attended a weekly art class for children at Elam, taught by the esteemed modernist painter A. Lois White. He went on to study still life under Ida Eise and later, as a secondary student, attended evening classes taught by John Weeks. Like White and Eise, Weeks is highly regarded as a painter, though he is particularly noted for his influence as an educator. Rumsey was introduced to photography when his brother gave him a Box Brownie. However, it was under Weeks that he first started experimenting with the medium's artistic potential. Rumsey truly came into his own as an image-maker in the 1950s, while in his twenties. At the time, photography was not considered a serious artistic medium, so the most progressive practices of the era were channelled into the thriving Camera Club scene.

Aside from the likes of Frank Hofmann and Barry Woods, who were also active in the camera club scene and with whom Rumsey shared common ground, Rumsey and his images were always an uneasy fit for the community. His output ranged from photograms, made in the darkroom by placing objects directly on the paper to manipulate the fall of light, to images of objects arranged according to their formal qualities, and austere vantages of the built world captured through Rumsey’s unique eye. Rather than exhibitions, the primary means of launching new work was a well-organised competition circuit where new images were assessed by a committee of experts. The feedback for one of Rumsey’s most accomplished images, Design No. 20, was particularly scathing. This photograph of a street positioned pictorial elements such as a drain, manhole cover, lamp post, and shadow in the same way that an abstract painting might use squares, circles, and vertical lines. The judges' comments included the following:

“This picture seems to defy all rules of composition and leaves me cold.”

“An unusual picture but afraid it doesn’t appeal to me.”

“I’m afraid I can’t get the feeling as Mr. Rumsey has.”

“Design No. 20… well I can’t get it.”

“No comment.”