Cryosphere - Online Exhibition

Jonathan Kay

Cryosphere

By Dr Babara Garrie

Cryosphere has been exhibited at the Jhana Millers Gallery, Wellington and the Ashburton Art Gallery and will show at the Hastings City Art Gallery in late 2022.

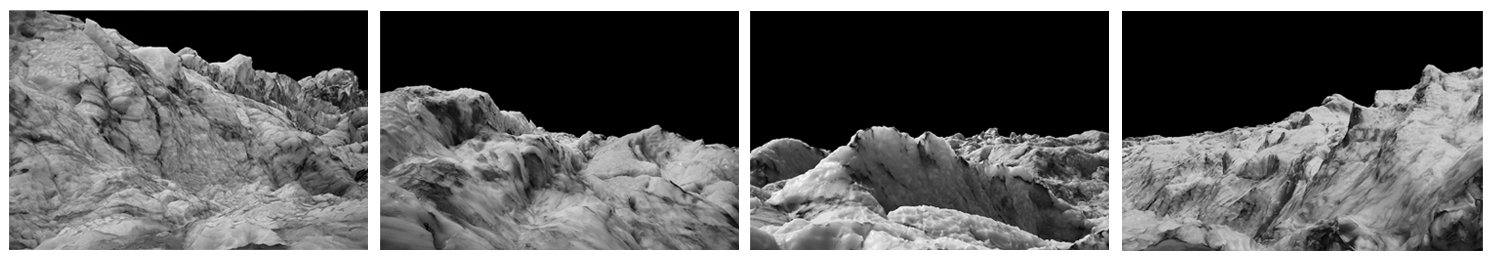

Jonathan Kay, Ice Field #12, Te Moeka o Tuawe/Fox glacier and Ice Field #6,Haupapa/Tasman, (2018) cyanotype photogram on cotton. (1150 X 2800 mm.) Install image Jhana Millers Gallery

The intensely coloured fabrics of Jonathan Kay’s Cryosphere cyanotypes utilise an early photographic technology to capture the forms and textures of the Fox and Tasman glaciers on the west coast of Te Waipounamu. Venturing onto the glaciers themselves, and down into the glacial lakes, Kay placed sheets of cotton soaked in cyanotype solution within the crevices, caves and arched formations of the ice, allowing their exposure to sunlight to transfer abstract patterns onto his human-made substrate. Water that leached from these surfaces inevitably became embedded within the liquid alchemy of the cyanotype process, wherein drips and splashes altered the exposures, creating compelling and enigmatic representations. The resulting works provide an uncanny index of the body of the glaciers, capturing their mutable, slippery surfaces in a delightful demonstration of the active transformations that characterise the glacial lifecycle.

Glaciers are constantly on the move. The névé at the source of alpine glaciers gathers snow, which over time compacts and turns into ice. With more snow comes more pressure, and more ice. Propelled forward under the momentum of its own weight, the ice creeps down picking up soil and rocks along the way. These sediments are carried along as the glacier slowly but powerfully carves its path over and through the mountainside. As it reaches lower ground and warmer temperatures the glacial ice melts, leaving behind its rocky deposits and becoming lakes and rivers of milky, mineral-rich water.

Aotearoa has many glaciers across both North and South islands. The Southern Alps in Te Waipounamu are home to some of our largest: the Tasman, Murchison, Hooker, Fox and Franz Joseph glaciers run somewhere between 27 and 12 kilometers in length each. Glaciers are particularily responsive to environmental change, naturally advancing and receding, but over recent decades scientists have expressed concern over the accelerated reduction of ice volume in glaciers of the Southern Alps (and around the world), primarily as a result of climate change.

Glaciers play a critical role in our ecosystems; it is their very cyclic movement that allows water to be recycled and redistributed. Ice melts, water evaporates, rain and snow falls. The effects of climate change on glacial processes therefore clearly have significant ramifications, yet it can perhaps be difficult to grasp the impact of changes to a structure or set of processes on the impressive scale of a glacier. Indeed, climate change itself operates on a scale so much larger than individual human experience – even while being intensified by human behaviour – that it can be a disorienting prospect to begin to even try and map what is at stake and how it might be addressed. Timothy Morton describes such phenomena as ‘hyperobjects’; entities that he writes are “of such vast temporal and spatial dimensions that they defeat traditional ideas about what a thing is in the first place.”[1] Climate change in this sense is difficult to fully apprehend for it resists the kind of clear boundaries we might desire.

Kay’s Cryosphere project is at least in part an attempt to bring a concern for climate change back to something more tangible, and to place it within a local context. Following in the footsteps of early European explorers in Aotearoa, Kay took to the mountains and glaciers himself seeking to document through photography his own journey within these landscapes. His images play with the conventions of landscape imagery; the tendency to aestheticise the landscape rendering it picturesque, romantic or sublime. In doing so, his works suggest a keen awareness of the power images have to both reflect and shape our understanding of the world. Where some examples of early photography in this region might have celebrated the awe-inspiring granduer of the environment alongside the achievements of the conquering explorer, Kay’s photographs offer something more nuanced and atuned to the plight of the glacier in this period of environmental crisis.

In his series of Observation images, Kay eschews the spectacular, attempting instead to draw our attention more intimately to the shifting forms, surfaces, textures and materials of glacial terrains. The title of the series of course alludes to a kind of detached act of looking, one that might suggest a sense of control or mastery of the land enacted through the lens. So too, ‘observation’ gestures to the ostensibly objective recording of scientific fieldwork. However, these black and white images are anything but detached or objective. Indeed, what makes them so persuasive is the sense of entanglement that they convey. Photographs such as Observation #2, for example, take us inside the ice. This image allows us as viewers to occupy the dark interior of an ice cave, and to look out past the shiny, dimpled walls of its entrance to the rocky moraine on the opposite side of the valley. Observation #3 and Observation #5, alternatively, embrace the mistakes and technical difficulties of trying to photograph in this challenging environment. These photographs were taken using infra-red film, which requires a red filter to be held against the lens of the camera. The glitches we see in the images are the result of the artist fumbling with the filter, foregrounding the embodied experience of the artist as he worked in weather conditions and topographies that may not always have been amenable to his human endeavour. And in all of these black and white prints, the photographs resist the dramatic effects of colour – a direct contrast with the vivid blues of the cyanotype works. The effect is to eschew the chromatic visual drama of, say, the coffee table photobook, and instead to create a space for encounters in which the felt and the enlivened are amplified.

Tracing with his camera its transformations from mountaintop to terminus, Kay poetically documents the glacier by both looking at and being in the environment. What emerges is a dialogue, mediated by Kay’s photographic processes, between the body of the artist and the body of the glacier; a dialogue that speaks of the inextricable yet increasingly fragile connections between human and more-than-human worlds.

Dr Babara Garrie is a Senior Lecturer in Art History at the Canterbury University

Content supplied

[1] Timothy Morton, Hyperobjects: Philosophy and ecology after the end of the world (University of Minnesota Press: 2013).

We need your help to continue providing a year-round programme of online reviews, interviews, portfolios, videos and listings that is free for everyone to access. We’d also like to dream bigger with the services we offer to photographers and the visual arts.

We’ve partnered with Press Patron to give readers the opportunity to support PhotoForum Online.

Every donation helps.