The Auction House, the Hammer and the NFT

The Auction House, the Hammer and the NFT

Report by Stuart Sontier and John B Turner for PhotoForum Online, March 2022

An NFT of a portrait of Charles Goldie at his easel fetched $51,250.00, while a portrait of the artist in his studio fetched $76,250.00.

Recently Webb’s auction house in Auckland put up two scans of early 20th Century glass plate negatives as NFTs for an online auction which ran from 28 January to 1 February 2022. Their first foray into this environment netted $51,250 for an image of the artist posing at his easel and $76,250 for the view of him surrounded by his painting in his studio. The auction estimates were between $5,000 - $8,000 each. Goldie’s paintings sell in the quarter million NZ dollars up to 1.5 million range.

Webb’s and the seller were no doubt delighted, but such is the state of NFT’s that it probably confirmed the general view that anything can be put up as non-fungible digital art and get a crazy-ass price.

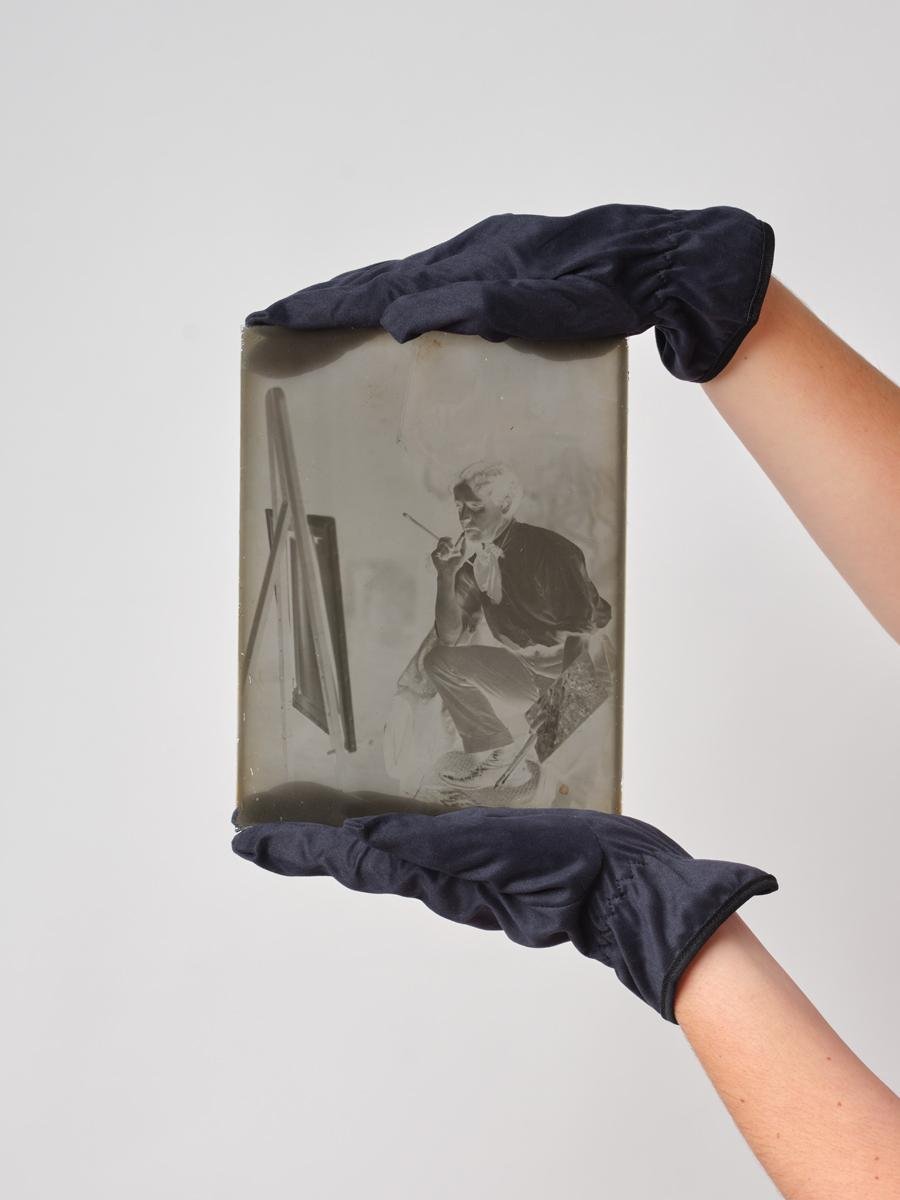

Having pulled off this historic event, which gained national and international attention, Webb’s seem a little unsure about whether they handled it the right way and what the result meant. The whole auction was a boots-and-all attempt to gain maximum interest. As well as the NFT for each work (essentially a digital receipt of ownership coupled with a jpeg file of a high-quality scan of each glass plate with certification of its minting), there was the original glass plate mounted in a hand-crafted wooden display box. Also included was a fine gelatin-silver contact print from each negative made by Jenny Tomlin. The addition of a small brass hammer drew international attention, which we will come back to later.

Rupert Farnall Studio, Devonport: C F Goldie at his easel, c1912. Vintage print sold by the International Art Centre, Auckland in 2017, for $NZ 5,000. Signed for his mother, ‘To Mater, From Charlie, March 1912’

Rupert Farnall Studio, Devonport: C F Goldie in his studio, c1908. Vintage print like one sold by the International Art Centre, Auckland in 2017, for $NZ 6,000. Signed ‘To R H Wardell, from his friend – CF Goldie, June 1937’ which indicates that Goldie had several prints made for publicity and gifts.

Rupert Farnall Studio, Devonport: C F Goldie in his studio, c1908. Cropped as presented in a New Zealand Herald news item ‘Charles Goldie photos and NFTs fetch record prices’, February 2022

To address green concerns, Webb’s astutely mentioned the environmental issues that have been aimed at blockchains in general and at NFT art in particular. Briefly, the Proof of Work (PoW) method of securing chains such as Bitcoin and Ethereum (where most high end NFT transactions happen) demands a lot of electricity to run the number crunching security mechanism. Although PoW enthusiasts argue that the electricity is often from renewable sources (or that Ethereum v2 is coming one day and will sort things out), Proof of Stake (PoS) blockchains are thousands of times less environmentally costly and are in use now.

The most common blockchain for PoS art is Tezos, which has been in common use for NFTs for about 12 months but has gained remarkable popularity especially amongst serious digital, code-based and generative artists as well as those from countries where the costs associated with using PoW chains are too high.

With these environmental concerns in mind, Webb’s has been trying to have its cake and eat it. The works were minted (created as an NFT) on OpenSea’s Polygon blockchain, a level 2 PoS system. Webbs noted though, that if the buyer preferred, the NFT tokens could be burned and re-minted on an Ethereum platform instead, thus appealing to serious buyers who know that a Polygon token has much reduced resale potential than would a token on the Ethereum chain. It does appear that the tokens were minted on OpenSeas Ethereum contract on February 12th. Webb’s are thus effectively trying to shift the environmental burden onto the collector rather than take an ethical stance themselves. One could argue that they are attempting to educate buyers, but the fact that they write knowledgeably about environmental concerns and then effectively offer the token on Ethereum shows they are hedging valuable bets. In a more recent auction it appears Webb’s have reverted to using Ethereum but now add carbon offsets to allay environmental concerns. Many in the ‘cleanNFT’ community don’t believe this is a valid option but most profit-driven enterprises feel they must take this route.

Whilst the hype around NFTs made a focus on price and blockchain a certainty, much less was said about the images themselves.

Charles Ninow, Webb’s Director of Art and auctioneer referred to “example[s] of the special qualities of old technology meeting, and being enhanced by, cutting-edge contemporary technologies and media formats”. Photographic historian John B. Turner disagrees. He contends that “it reflects a very conservative choice of images, based not on the significance of two fine promotional photographs by a virtually unknown Devonport photography studio operator but of its subject: ‘unquestionably one of New Zealand’s greatest and most celebrated artists’.”

The obvious next step, he suggests, would be to destroy a Goldie painting in return for a rare uncropped newspaper photograph as an NFT.

Both images feature renowned New Zealand painter Charles Goldie at work. The first, a staged close-in view of Goldie and paintbrush squatting by his easel and canvas; the second, a wider view of Goldie at the easel in his studio with many of his famous paintings on the wall behind. Ninow discussed the fine detail available from the “6x8” inch plates (and the scans) noting that next to Goldie’s foot in the closer view there can clearly be seen a photograph from which he likely derived his painting.

The photographs are credited to Rupert Farnall Studios but might not have been made by Farnall himself. Farnall had a studio in Devonport and filed for bankruptcy on 27 March 1920. Little is known about him currently but a Mr Rupert Farnall is known to have enlisted for military duty in 1917, and might also have owned a florist’s business and a drapery.

It’s not clear who the sellers were, nor the provenance of the plates. In the NFT world this is of interest because usually royalties are assigned to the minter of the NFT. This means that if the NFTs are on-sold at any time, a secondary royalty will (by means of the smart contract at work on the minting platform) automatically pass to the minting crypto-wallet. Normally this is to protect the original artists’ stake in their work. In this case it may pass to the seller, or perhaps to the estate. Webb’s did not return a request for questions to this effect.

Webb’s auctioneer Charles Ninow discusses the hammer during an Instagram live video.

What about that hammer?

During a Webb’s Instagram video interview Charles Ninow implied that they were playfully riffing on Damian Hirst’s idea of investigating the value of the original when they included the brass hammer in their auction. During this he asks “Is the scan of the image more real than the negative?”

It’s an old idea which was mined earlier in Dada and conceptual art. Ninow did not state the purpose of the hammer initially but later gave strong hints, stating that “the buyer could do what they liked” with it, before coming clean in the video, laughingly suggesting that the new owner could smash the glass plates themselves, on-camera. Perhaps it was an attempt to cause public outcry from photographic historians.

Ninow’s sense of humour and a shrewdly cultivated disdain for the real object was likely an attempt to push attention to the digital version, with a nod toward libertarian techno optimists who claim that to digitise is to evolve. It’s unclear if this apparent lack of concern for the original object was genuine or just clever marketing but, by making it so easy, (and potentially twitch-able on social media) such a suggestion, however whimsical, perhaps could make a physical attack on the negative more likely.

As it was, Radio NZ reported that the hammer was withdrawn from the auction.

While that news item suggested it was a commentary on where the aura of an artwork lies (in a reference to Walter Benjamin’s 1935 essay "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction"), what would be the problem if the NFT owner destroyed the original glass plates? What would be lost when the images are embedded or enshrined in high quality digital files which may make prints as good as an original?

One obvious disadvantage would be the loss of any possibility to interrogate the plates for more information; using forensic scientific methods to scrutinise the emulsion makeup for more accurate dating, for instance. Some processes available today could help pinpoint where the glass and emulsion were made. Future analytical methods applied to the original plates might produce levels of information that digital scans might miss.

John Turner wrote about the valuable nature of originals to remind art gallery and museum professionals nearly 40 years ago:

“To see the personal signature in photographs, it is usually essential to study original, or first generation works. Original, or "vintage" prints, as collectors like to call them, are those made by, or under the supervision of, the photographer in her/his lifetime. They are primary artefacts, as distinct from copies which can be anything from two to four generations removed from the original. Original negatives are also vital primary artefacts.”

Akin to a musical score in practice, (each print being an "interpretation" of the negative), negatives can provide insights that even original prints fail to yield, in that they might show edge information cropped in printing, or reveal detail lost through under or over-printing, or by fading of the print.” – John B Turner: ‘Some Notes and Queries on the Collecting of Photographs by Libraries, Museums and Art Galleries in N.Z.’, AGMANZ News, June 1983.

Returning to this theme recently, Turner explains:

One of the great advantages of digital imaging is how brilliantly the optical and aesthetic quality of original photographs can be so convincingly duplicated and presented on the interface of our computer displays. That magic dissipates when the image is digitally projected, shrunk or overblown on the monitor of a computer or other digital screen.

With appropriate technical skill and sensitivity, it is possible to almost perfectly replicate any photographic image in a fine digital or hybrid print that can equal the distinct beauty of the early carbon archival printing processes, the finest photogravure printing, or layered multi-colour glory of the best of today’s offset printing, for example.

There are vast numbers of analogue negatives waiting to be printed (by contact as per the Rupert Farnall Studio’s images or by enlargement) or scanned or simply copied with a digital camera as most now are. If faded original prints exist, such as those of these same Farnall portraits of Goldie, sold by the International Art Centre in Auckland in 2017, (the closer version for $NZ,5000 and the wider studio view for $NZ6,000) there is more than one choice available. One is to make a faithful digital colour replica to show the faded state of the print, along with the visible details, and another is to restore the faded tones, colours, and details to approximate its original state. In both cases a high degree of enlargement would also show the texture of the paper fibres as well. Compared with that, if expertly made, digital scans made directly from a negative, or copies made with a digital camera, can be enlarged considerably without showing the texture of the emulsion that gave birth to the negative by chemical means.

Any direct comparison of a digital copy made from scanning the negative, vis-à-vis scanning and enlarging from a contact print, is bound to demonstrate the optical superiority of the former, because a negative (or transparency) can record a tonal scale (contrast range) of about five times more than the most luscious print. Digital photographs promise the same unique advantage of photography as a print medium due to its ability to make exact multiple originals, although in practice the physical template of both will deteriorate with use over time, as will happen to the Farnall glass plates even if they are never printed from in future.

None of this fully addresses the question of aura in the physical or digital realm, but current examples of NFT artists bundling physicals with their NFT sales does suggest that physical artworks do still have some standing. In relation to photographs, Walter Benjamin argued that lack of uniqueness (ie reproducibility) negated an artworks’ aura. The issue becomes more complex when artificial scarcity is introduced – either in the physical limiting of edition size (taken to the extreme by destroying a negative), or the limiting of edition size of the NFT (some platforms only allow editions of one, other platforms allow editions of any size). Photography has dealt with these complexities in numerous ways (one being to ignore it completely) and it’s something that auction houses can play to their advantage at times but they are not likely to raise the loss of authenticity that Benjamin contended.

We don’t know who the “expat Kiwi living overseas’ who purchased the “Goldie” NFTs was, although a blockchain analysis confirms that both NFTs were transferred to the same wallet on 16 February 2022. We also don’t know whether the purchaser has a curatorial, professional or a financial interest in the items. We can track wallet owners because the blockchain wallet can be monitored to see if they are resold, although it doesn’t reveal the identity of each owner/investor. It may not be clear what has happened to the physical items until the new owner shows or sells them.

Commenting on the significance of this NFT event, Turner, like many skeptics, tends to see the NFT as a new gimmick; just another method of conspicuous consumption from those with disposable incomes. Indeed, another colleague referred to the NFT component in the auction as a 'black box of sexiness to buyers'.

The state of play for artists making NFTs is in its infancy and more complex than most realise. The asking price or bidding outcomes can be anything from 20 NZ cents up to US$69 million. NFTs cover a diverse range of art, personal profile pics, and collectibles, alongside a wide range of try-hard efforts to get rich or make fools of others by offering bottled farts, artists’ shit (interesting but another old idea), traffic tickets (Billy Apple did that with more panache 20 years ago), and embryonic eggs.

Well-known artists have dabbled and been drawn into minting NFTs. Damien Hirst notably attempted to question the value base of the digital vs the physical with his ‘The Currency’. He issued both digital and original paper versions of the work in an edition of 10,000, with the proviso that the purchaser could keep only one or other after one year.

More interestingly, artists such as New Zealander Simon Denny, with an interest in global finance and power, play with the concepts and technologies that run these ephemeral spaces. Kevin Abosch, an Irish pioneer in crypto art, also works conceptually with aspects of blockchain technology.

There is a wealth of overlooked experimental digital and web-based art ranging back decades, which is prime space for NFTs. Many of these artists, often working in a vacuum for years are essentially being ‘discovered’ as a result. Like many artists struggling to survive, they are taking advantage of what might be a short window of sales, or might culminate in a way that a more diverse range of artists can make sales while remaining independent.

Webb’s and Charles Ninow deserve kudos for jumping in to test the waters here. Whilst artists and overseas curators embraced NFTs relatively early, New Zealanders and Australians appear to have all but ignored this controversial new medium (apart from a few get rich quick attempts). So far, to our knowledge there has only been one (private) physical exhibition/showcase of New Zealand based NFT artists, at inHaus, in Christchurch in January 2022. A few artists such as Gerry Parke have dabbled in minting physical work in the digital space. The Glorious platform (backed by names such as ex All Black Dan Carter and using an Ethereum-based system based on CENNZnet blockchain which claims to be climate negative by way of offsetting), offers a high end gated community of artists which finally launched this March, after several attempts last year.

Now that the money is on show, we can expect that other Aotearoan artists will hurry to improve their blockchain knowledge, while galleries will be looking for digital expertise to bring their traditional artists on board.

Page from International Art Centre’s catalogue, Auckland, 2017 showing the vintage Farnall prints which sold for $NZ 6,000 and $5,000 respectively.

A non-fungible token (NFT) is a non-interchangeable unit of data stored on a blockchain, a form of digital ledger, that can be sold and traded.[1] Types of NFT data units may be associated with digital files such as photos, videos, and audio. Because each token is uniquely identifiable, NFTs differ from blockchain cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin.

NFT ledgers claim to provide a public certificate of authenticity or proof of ownership, but the legal rights conveyed by an NFT can be uncertain. NFTs do not restrict the sharing or copying of the underlying digital files, do not necessarily convey the copyright of the digital files, and do not prevent the creation of NFTs with identical associated files. - Non-fungible token - Wikipedia

Author notes

Stu Sontier is a long-time PhotoForum member and experimental photographer making digital work. Recently he has been minting environmentally clean NFTs on the hicetnunc platform (now teia.art) run on the Tezos PoS blockchain. He lives in Auckland.

John B Turner, the founding editor of PhotoForum and photo historian is less technically inclined but is slowly learning from Stu Sontier’s enthusiastic explorations of new image making techniques despite the jargon that accompanies so much of it. He lives in Beijing.

We need your help to continue providing a year-round programme of online reviews, interviews, portfolios, videos and listings that is free for everyone to access. We’d also like to dream bigger with the services we offer to photographers and the visual arts.

We’ve partnered with Press Patron to give readers the opportunity to support PhotoForum Online.

Every donation helps.