NEW ZEALAND’S PHOTO TREASURES HEADING FOR THE TIP? - Part 10

Notes on the collection of photographers’ collections for posterity

A PhotoForum discussion paper by John B Turner

Part 10: A case for more curators, The Simple Image, and Barry Clothier & John Turner’s Artides Gallery exhibition in 1965

Collecting institutions are demanding photographers provide more detailed annotated and catalogued information about their work than was expected in the past, before their collection will even be considered for inclusion. Thus, there is a corresponding need for many accomplished photographers who perhaps vainly assumed that their pictures said it all, to be coached in how to describe the content and form of their images with as much clarity as they can provide for our picture archives.

John B Turner

01: Introduction

02: Te Papa

03: Significance & Archives for Artists

04: Gael Newton: Parting with your art & Photographers’ Archives

05: Auckland Art Gallery & Alexander Turnbull Library

06: Auckland War Memorial Museum & Auckland Libraries

07: Internal Affairs & Heritage Departments

08: Canterbury Museum & Christchurch Art Gallery

09: Collection case studies: Tom Hutchins, Paul Gilbert, Max Oettli & Barry Myers

10: Curating, Barry Clothier Simple Image show, and Clothier/Turner 1965 Artides show

Figure 10.01: Mark Beatty, Alexander Turnbull Library: Installation view of ‘The Simple Image: photographs by Barry Clothier’ exhibition, Te Puna Foundation Gallery, NZ National Library, Wellington, with detail of Sal Criscillo’s portrait of “Bazza” Clothier. (Ref 20210409_ATL_OS_Simple_Image_011 received 17 March 2022). Courtesy Alexander Turnbull Library

A case for more curation

Notes about learning on the job, mentorship, issues of fact and opinion, quality control, public relations, transparency, owning up when things go wrong, and making amends.

I am curious that there are so few designated curators of photography in New Zealand and that our heritage institutions and libraries seldom give their most experienced staff that title, no matter how qualified, enthusiastic, and active they are in that capacity. It might be due in part to the structure of public service glass ceilings, but equally, it might be that the supposed glamour of being a curator and developing a prominent public persona in the field invokes the tall poppy syndrome and ridiculous displays of envy of the kind I observed between the art elites of the US East and West coasts over the photography John Szarkowski, Edward Steichen’s successor, chose to feature at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in New York. (Hardly any of Szarkowski’s critics that I met or read in the US in 1980 seemed able to acknowledge that it was up to them to present alternative theses if they didn’t agree with his, rather than try to mute his sonorous voice.)

There is no doubt in my mind that having too few curators with the full support of their institutions has put the brake on progress and rallying public support when it comes to demonstrating the significance of heritage collections and inspiring the next generation of specialists to pick up the baton. And it seems unfortunate how fragmented and unsupportive the broad chain of heritage libraries appears when outstanding exhibitions such as Charlie Dawes: Everybody’s Artist photographer of the early 20th Century Northland, created by Keith Giles’ team at the Auckland Central Library in 2019, and the Ken Hall – Haruhiko Sameshima collaboration, Hidden Light on early Canterbury and West Coast photography, created by the Christchurch Art Gallery, for example. Both deserved much bigger audiences.

According to the 2018 New Zealand Census, (which warns of flaws), 459 people identified themselves as museum or art gallery curators, with roughly 140 in the Auckland region, 100 in Wellington, 65 in Canterbury and 30 in Otago.

By contrast, over 4,038 librarians were listed, with over 1,200 in Auckland, 800 in Wellington, nearly 500 in the Canterbury region, about 300 in Waikato, and just over 200 in Otago, with similar totals in the Whanganui-Manawatu and Bay of Plenty regions, among the biggest regional clusters. How many are responsible for pictorial collections, and how many are photography specialists is not at all clear.

The dismal failure of academia in New Zealand to advance study in the histories of photography is one factor that does not bode well for furthering informed discussion and building a broader pool of photography specialists, but that deserves a separate survey. There are, however, a small number of tertiary art courses on curatorial training, such as the University of Canterbury’s postgraduate diploma in Art Curatorship, the postgraduate diploma in Museum Studies at Wellington’s Massey University, and an Honours level course in art writing and curatorial practice offered by the Art History Department of the University of Auckland which supervises student research in the University’s Museums and Cultural Heritage programme.

To improve training for its staff, The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa recommends study for the New Zealand Certificate in Museum Practice offered by ServiceIQ, an accredited Industry Training Organisation (ITO), for on-job training recognised by the Associate Minister of Education (Tertiary Education) under the Industry Training Act 1992, to set national skill standards for various industries.

While training to be a funeral director or embalmer is included, the possibility of becoming a picture or photography librarian is not even mentioned in the governmental careers database. Wintec Waikato’s online advisory to students lists “te reo Māori, Pacific studies, history of arts, history and classical studies, science, English, construction and mechanical technologies, and painting, sculpture, photography, printmaking combined” as useful subjects for a tertiary entrance qualification but concludes that “Chances of getting a job as a curator are poor due to low turnover and the small size of the occupation”.

Figure 10.02: Curator Job Opportunities POOR. WINTECH Waikato careers database. (Screenshot 2022-02-12 072731)

Perhaps these are among the reasons why the growing crisis about the non-collection of photographer’s collections is under the radar of the public and powers that be?

Specialist curators of anything are few and far between in New Zealand and those who have proved themselves weren’t formally trained but learnt on the job the many skills needed to balance competing institutional demands that hamper productivity in their chosen fields. Not everybody can create a nuanced exhibition, write a book, become a competent public speaker and art diplomat able to persuade their colleagues to support a cherished new project, let alone deal with angry artists who feel neglected for whatever reason, or bring on potential patrons. Although I only met him once, and I know he is used to being respected as a distinguished academic, art historian and curator around the world, it is unfortunate that New Zealand could not compete with Oxford University to continue the brief but notably productive tenure of Professor Geoffrey Batchen at Victoria University in Wellington. Along with completing exemplary exhibitions of photographs for Victoria’s Adam Art Gallery and New Plymouth’s Govett-Brewster Gallery, he delivered an honest critique of Te Papa’s less than ideal support for its specialists to present New Zealand photography to the world, with the exhibition hastily ordered to accompany the publication of Athol McCredie’s New Zealand Photography Collected book, previously noted.

Batchen, with polite diplomacy, identified the lapse of quality control as a historic systemic failure of the museum, and not, as many imagined, a disguised personal attack on its photography staff of the kind that curators must learn to accept from people unwilling to formally present contrary views for all to consider.

It should also be remembered that photographers in New Zealand academia, including Wayne Barrar, Lloyd Godman, Gavin Hipkins, K T Ho, Megan Jenkinson, Allan McDonald, Anne Noble, Marcus Williams among them, and independent curators such as Greg Burke, Peter F Ireland, Robert Leonard, Ian Macdonald and Justin Paton were among those who early set the high standards of presentation and curatorship that should be expected of a national museum.

Opening the door for a broader and deeper discussion of the issues raised toward achieving genuine improvements to the situation is the central purpose of this investigation which seeks to understand and qualify issues revealing serious problems that threaten the laudable aim of “preserving New Zealand’s documentary heritage and ensuring a full and accurate public record…” For that is what is espoused by the same Department of Internal Affairs that is ultimately responsible for the folly of allowing our National Library to do away with actual books (which are often art works in their own right) while proceeding to digitise everything. Thus, it is not difficult to imagine similarly reprehensible treatment by design or default, over the non-collection of analogue photography depicting this country in the second half of the 20th Century.

Paper qualifications are one thing I don’t have, except for a Certificate of Proficiency in motorcycle riding, and as much as I was told how necessary guild certification was to my ascension on the academic ladder (after my rare entry into a NZ university without academic qualifications in 1971 thanks to the lobbying of Tom Hutchins), I was more interested in experiencing what it was like to be a high level student for the first time in my life, to study under world leading scholars, when Van Deren Coke invited me into the prestigious masters programme that he and Bill Jay taught at the University of Arizona, Tempe. That was in 1990, a very busy time, when I imagined that I could also get on with completing my contribution to the anthology New Zealand Photography from the 1840s to the Present (1993) which William Main and I had embarked on before my family skipped to the US for a year. Subsequently, I decided that the time and cost of finishing an MFA was less important than getting on with cherished projects at home. Besides which I had not only been challenged by brilliant photographers and teachers such as Mark Klett, but chastened to meet many clever university graduates without a cause.

It’s tricky to get the backing needed to explore innovative ideas if you work in a government institution: changes that aren’t necessarily brilliant but fall outside the mindset of the leaders of a department or organisation, and the resulting pushback is not exclusive to the public service sector. For instance when I was working as the sole photographer at the Dominion Museum in Wellington in the late 1960s and was so excited by the wonderful and telling historical photographs of the Burton Bros, James Bragge, G Leslie Adkin and others that I pitched the idea of making high quality offset art prints to promote and sell at the Museum. Alas, the suggestion went down like a lead balloon with the Director and top management - all scientists - unwilling to even explore the possibility.

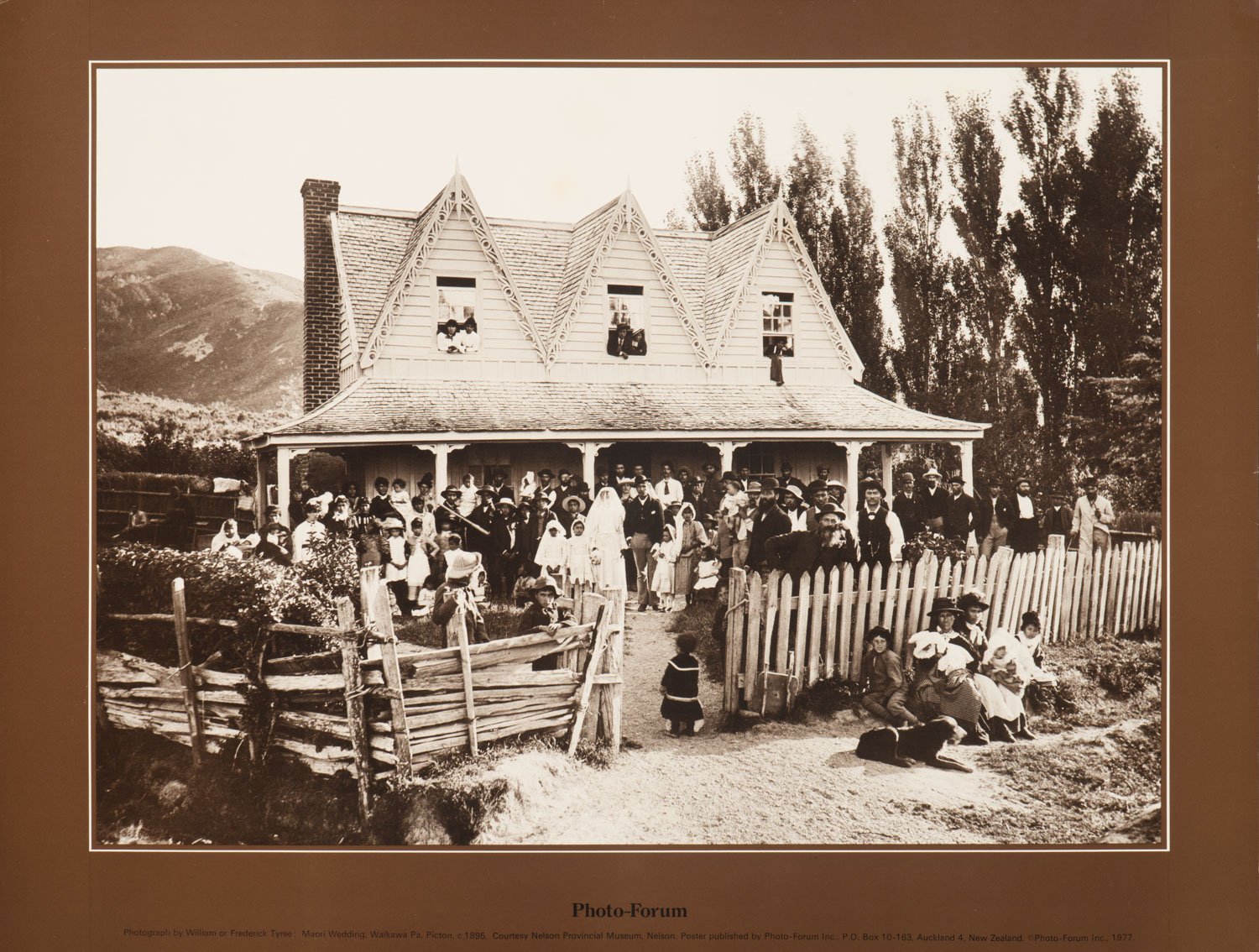

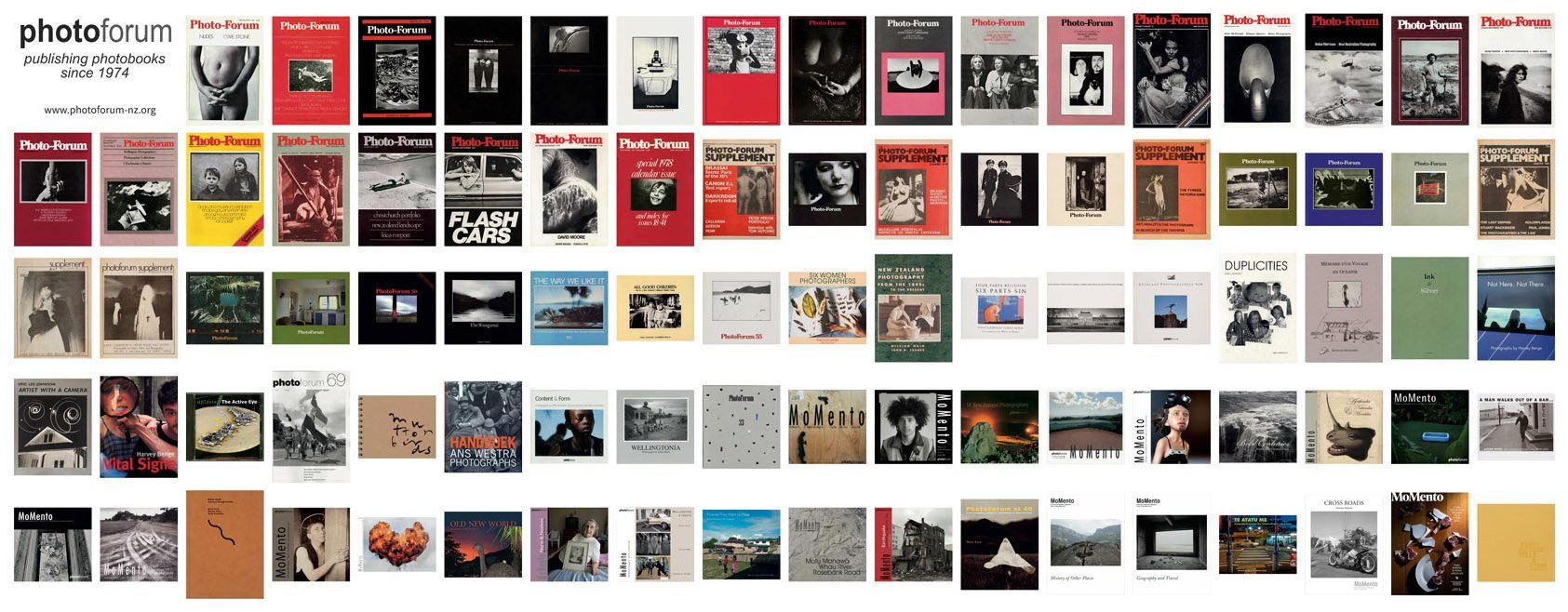

When I tried again about seven years later with PhotoForum Inc., we sold hundreds of high quality duotone reproductions of images by Burton, Bragge, and Muir & Moodie – all sourced from the Museum’s collection, along with the clear favourite (from the Nelson Provincial Museum’s remarkable but regrettably under-utilised collection) the classic Tyree “Maori Wedding” photograph commemorating a Love family gathering at Waikawa Pa in Picton near the end of the 19th Century. Sales not only helped PhotoForum keep afloat but also established how serious we were about promoting outstanding photographs. Even today the amalgamated Museum and National Art Gallery, today known as Te Papa, neglects that potential PR and revenue stream.

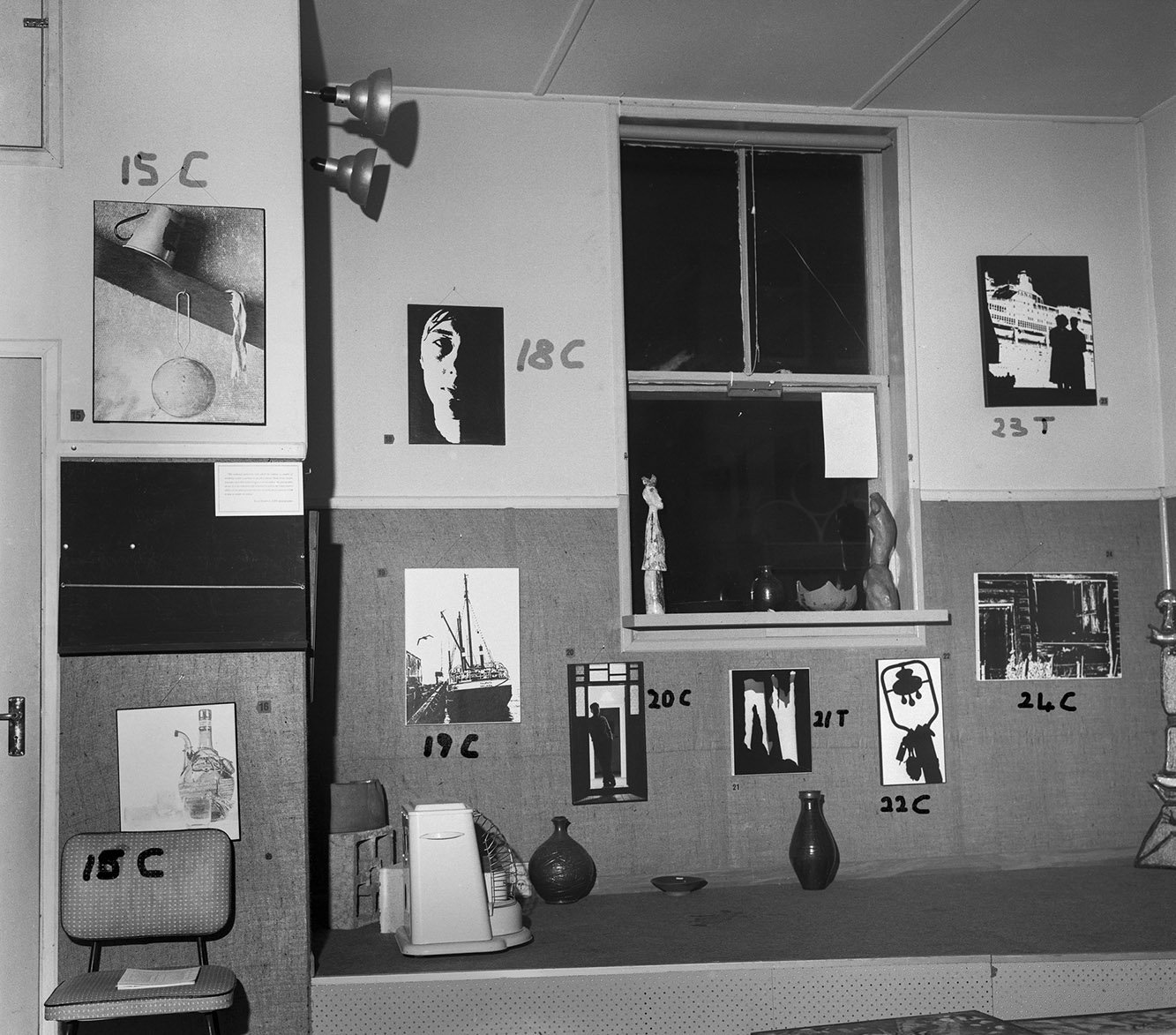

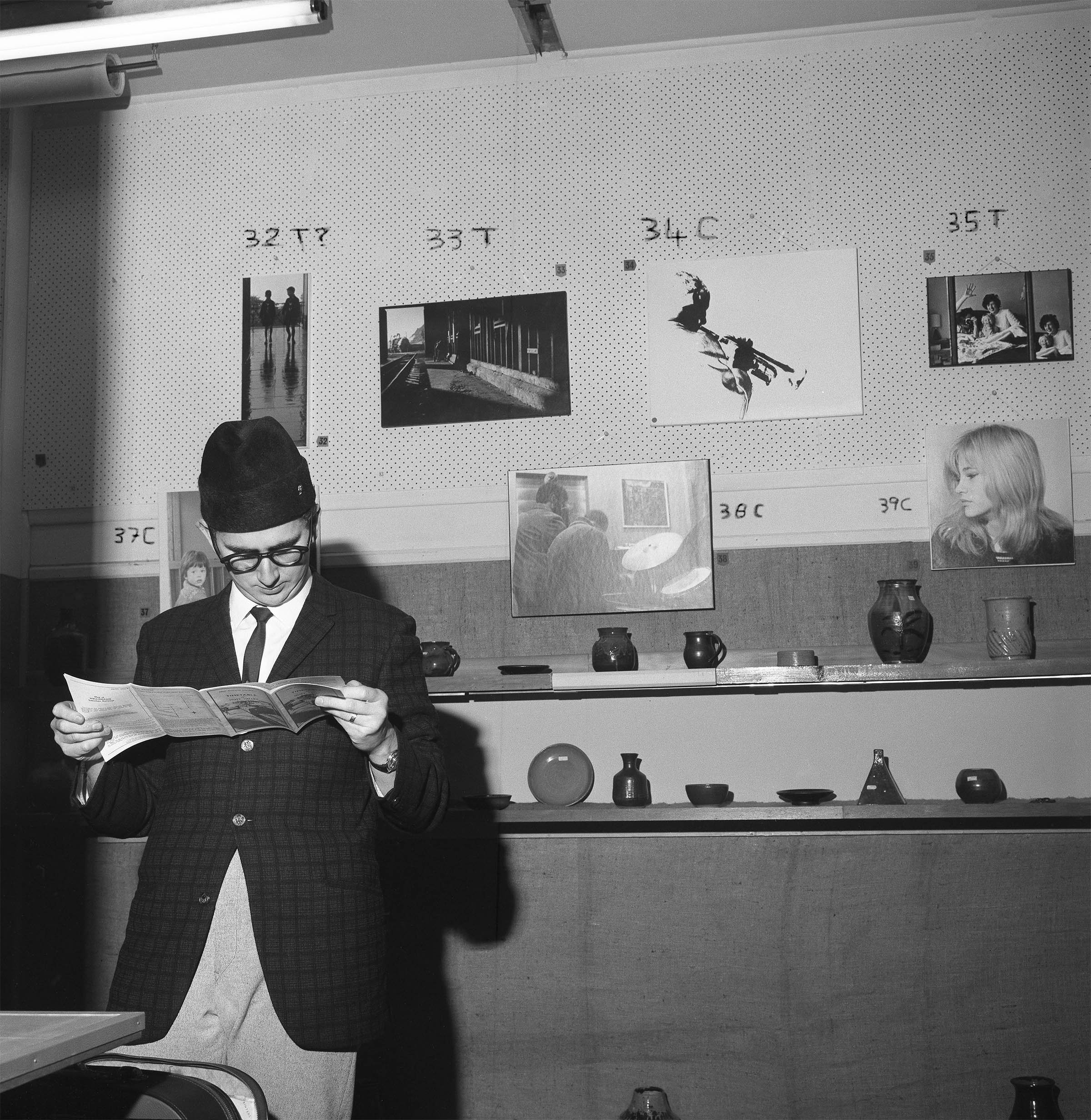

I am reminded also of the only way John Ritson, the education officer at the National Art Gallery, and I could get photographs shown there was to present our exhibition Looking & Seeing in the small galleries set aside for their education department. Our modest exhibition proved quite popular so after showing it there in 1968, John managed to send it off to nine other venues around the country. For the record the full roster of photographers was Don Campbell, Max Coolahan, Ross Leigh Hawkes, JHG Johns, Olaf John, William Main, Fiona Pitt, Theo Schoon, John B Turner, and the 19th Century Dunedin Burton Bros studio.

Illustrations of the catalogues of these late 1960s exhibitions are shown below with the schedule for the Looking and Seeing exhibition, along with the now famous Tyree photograph, c.1895 as a duotone art print. The Maori in Focus and Nineteenth Century New Zealand Photographs exhibitions also toured New Zealand.

(Click on images to enlarge).

The inspiration for my work on these exhibitions came from what I had read about the surveys of contemporary photography initiated by Nathan Lyons, at the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York, when he was the assistant to Beaumont Newhall, the distinguished photographic historian who started his career as a librarian at The Museum of Modern Art in New York and became their first Curator of Photography in the 1940s. Lyons organised an “International” survey of contemporary photography in 1963, and in 1967 followed it up with Photography in the 20th Century, a major touring exhibition which could have come to New Zealand if the then director of our National Gallery had been more adventurous.

Nevertheless, the Lyons and Newhall examples helped prompt me to pitch the idea of the Maori in Focus (1970) exhibition to Ian North as the Director of the Palmerston North Art Gallery, and to get the enthusiastic support of John Maynard, the young first Director of New Plymouth’s Govett-Brewster Art Gallery for the Nineteenth Century New Zealand Photographs exhibition I curated for them. That also toured the country and the modest, atrociously printed catalogue sold out. The National Art Gallery were not so keen on my proposal for a survey of New Zealand contemporary work (which later became The Active Eye survey of 1975), while in the interim the Auckland City Gallery supported my abbreviated version: Three New Zealand Photographers: Baigent Collins Fields which, as well as touring, proved that it was as difficult for local printers to do justice to the duotone printing inspired by the likes of Ansel Adams for his gorgeous books, as it was to get the new “perfect” bookbinding glue to stop the pages falling out.

Learning on the job inevitably means making some mistakes, so it is a good reminder whenever I see my Nineteenth Century New Zealand Photographs catalogue that the cover image was not made by Dr AC Barker, but his son, Sam; and that the interior with the magnificent organ belonged to Australia and its history of photography; unforgivable flaws that may have shamed the Govett-Brewster into never ever mentioning that exhibition during the 50th anniversary review in 2020?

What do photographers expect from collecting institutions regarding how their work is presented after they die?

Why do practitioners assume that collecting institutions will accurately represent their work and concerns after they die? And what steps can be taken to ensure that their work gets a fair airing? I don’t mean sycophantic “world according to me” displays, but considered and possibly revelatory critical analysis that also acknowledge the contradictions, myths and conceits that we humans accumulate for recycling intentions and protecting reputations? That is one of the big elephants in the room that if noticed at all is virtually never mentioned when work is being transferred from its maker to its marker. How can institutions and influencers be incentivised to check out overlooked bodies of work when they are so often looking for the fashion equivalent of click bait to attract the crowds, or keep buffing the reputations of “names” to reinforce the status quo for the very same reasons?

It’s not exactly a Faustian bargain that photographers enter when they hand over the cream of their lifetime’s work to an archive, but it’s a huge unknown requiring a high degree of trust. “Parting with your art” as Gael Newton calls it, is something akin to signing up for an insurance policy in the hope not only that it won’t be needed, but if tragedy does strike, not all will be lost. Or like putting one’s body into the hands of a surgeon. Relinquishing control over a body of work requires a mix of blind faith, fond hope, and fatalism, along with the relief that something is being done to solve a practical and perhaps even existential problem.

Personally, I have always admired librarians (along with translators) as special people who exemplify the public service ethos by habitually going out of their way to be as helpful as they can to their customers. Librarians frequently accrue extraordinary familiarity within an area of specialisation and expertise and usually know more than anybody else about the treasures in their archives. And that is why I have argued that more of them should be encouraged to curate exhibitions and share their insights through various media.

Going public about a library’s treasures and needs not only shines the light on them for the public good but encourages full support from those who hold the purse strings.

That said, we all know that mistakes and misunderstandings are inevitable in every personal or collective endeavor and must be guarded against. So rather than thinking of the library or art museum as a hallowed hall of fame for our work, it might be more realistic for photographers to imagine them as giant scrapyards of parts from which anybody can pick and choose components to combine or reuse according to their personal sensibility and fancies?

There have already been at least two, perhaps more, meetings of photographers, curators and picture librarians to discuss issues around the collection and non-collection situation linked with digitisation, but the sessions at Massey University and Te Papa involving many leading specialists and mentioned earlier appear to have been ineffectual, and their deliberations neither recorded or shared with the wider community. I don’t assume that those responsible haven’t warned their organisations about the growing problems but know from my own experience how difficult it can be to get managerial support to act on key issues before it is too late.

As far as our National Library is concerned, however, New Zealand’s leaders seem more concerned about creating monumental buildings than training curatorial staff in the wisdom necessary to compile and justify archives of significance. The National Library’s excuses for their recent rejection of actual books in favour of digital copies does nothing to instill confidence that our libraries won’t try to decimate our pictorial archives in a similar manner.

And the answer to the question of “What control do we photographers have over the use or misuse of our work when we are dead?” remains to be seen.

What, for example, are the checks and balances in place to ensure that one’s images are fairly and accurately characterised through the process of cataloguing in the first instance, and impartially curated or promoted? Unable to predict future needs, it is understandable that few if any donors can even expect that their work will be the focus of such attention? Our libraries, traditionally, have not been very active when it comes to publishing catalogues or articles about their many unique holdings. Increasingly, useful digital displays online and off are becoming the norm. And with it there are already signs of the danger that PR designed to boost sales could substitute for critical analysis and use, such as when instead of displaying original analogue prints – which are the only things that make sense for serious researchers and connoisseurs to study (and justify preserving them in the first place) – second or third generation copies are presented.

Looked at another way, it is obviously a huge gamble to expect others, who have not shared similar experiences during their lifetime, to really understand the mindsets and intentions behind the making of significant photographs. So the increased emphasis on why we photographers should take the time to clearly spell out our intentions, whether in written or oral form, to accompany our images is perhaps long overdue. Librarians and historians specialise in bridging the gaps of generational memory, so it is obviously in the interest of practitioners to guide others through their more nuanced and less self-explanatory work, at least. It might help to remember that while we as practitioners can be picky about which of our peers we were happy to associate with, there can be sound reasons for future researchers to posthumously clump our work with that of our perceived rivals, inferiors or betters, and even outliers we have never heard of, in their attempts to present our legacy in the broader historical context.

‘THE SIMPLE IMAGE: THE PHOTOGRAPHY OF BARRY CLOTHIER’ 2021

A not so simple case study

John B Turner, Beijing, May 2021 - March 2022

Figure 10.03: Sal Criscillo: Barry Clothier, Wellington, 1965. Courtesy of the photographer

[This chapter is based on my intended review of this exhibition which was not completed because it took too long to gather the facts and visual illustrations. My research instead revealed unexpected lapses of quality control and surprising absence of basic documentation about it from the host library so these issues became the new focus as part of my broader inquiry into a growing crisis over the non-collection of photographers’ collections in New Zealand. As far as I know, apart from a piece by Audio Culture as part of its coverage during “Music Week” in May 2021, nothing resembling an exhibition review was attempted by anybody based in NZ who might be expected to do so.

Consequently, as well as describing the process of my research for this chapter and observations about Barry Clothier’s early work, I have added a description of the joint exhibition he and I had in Wellington in 1965. And in the process I have included discussion of the use-value of the proof sheet in analogue photography for the “born-digital” generation, plus basic issues to do with the description of photographs in cataloguing (particularly in regard to online data), and asking the big question raised by The Simple Image experience, about what photographers should expect from collecting institutions in regard to how their work is treated after their death].

In November 2020 I was alerted to an upcoming New Zealand National Library exhibition of photographs by Barry Clothier (1940-2017) when its curator Matt Steidl, Team Leader of Research Enquiries at the Alexander Turnbull Library, emailed me about the possibility of including one or two of my photographs of Barry taken in 1965 that he had located on my website. That was the good news; but on enquiring further about the show I learned for the first time that my friend had died three years earlier. (I have since been told that he had experienced serious health issues and didn’t want his funeral to be advertised.)

The exhibition, titled The Simple Image: the photography of Barry Clothier, opened on 9 April 2021 in the National Library’s ground floor Te Puna Foundation Gallery and was scheduled to conclude on 10 July, while a second version of a more modest early display was being prepared for a bigger space upstairs in the Alexander Turnbull Library’s Reading Rooms on level one of the National Library building situated in Molesworth Street, directly across from Parliament Grounds in Wellington, where unhappy campers are (mid-February 2022) protesting the New Zealand government’s handling of Covid-19 and Omicron preventative measures.

Figure10.04: Mark Beatty, Alexander Turnbull Library: Detail, part of final wall panel for The Simple Image: the photography of Barry Clothier, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, 9 April 2021. Courtesy Alexander Turnbull Library

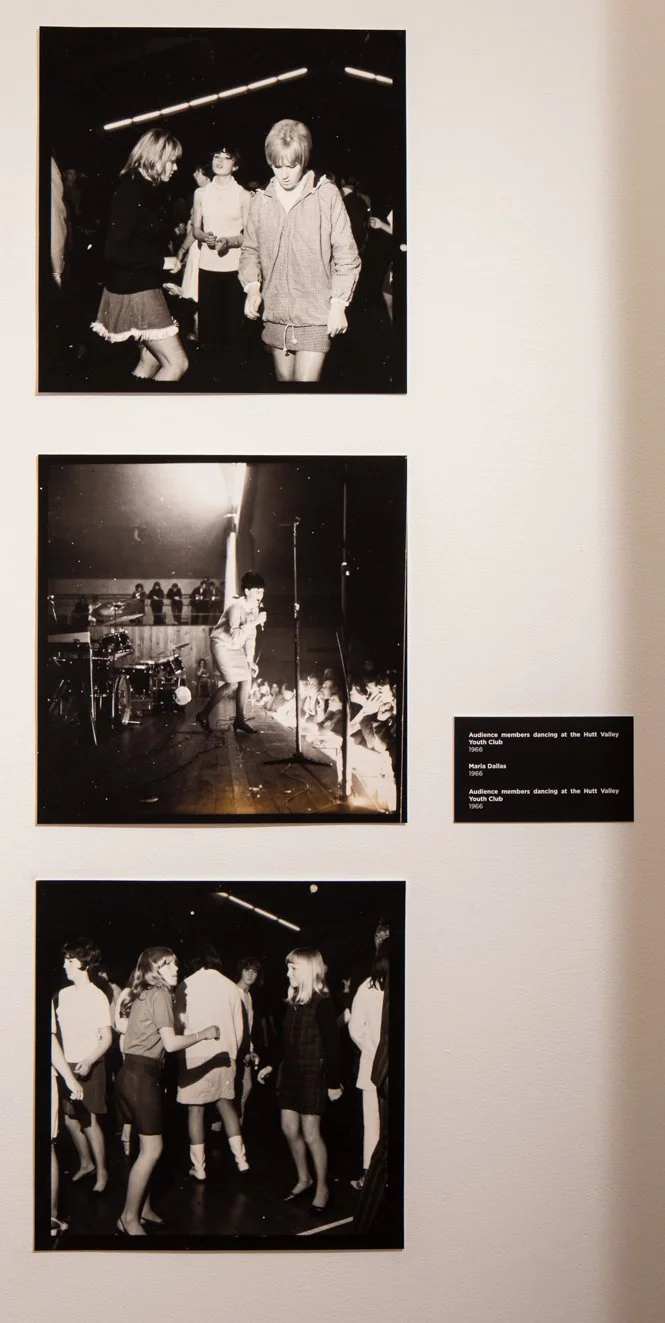

Figure 10.05 National Library catalogue Barry Clothier's photographs of musical groups in Wellington 1960s. (See Figure 10.40 below for updated description version)

Figure 10.06: ‘The Simple Image…’ - Main text panel. Courtesy Alexander Turnbull Library

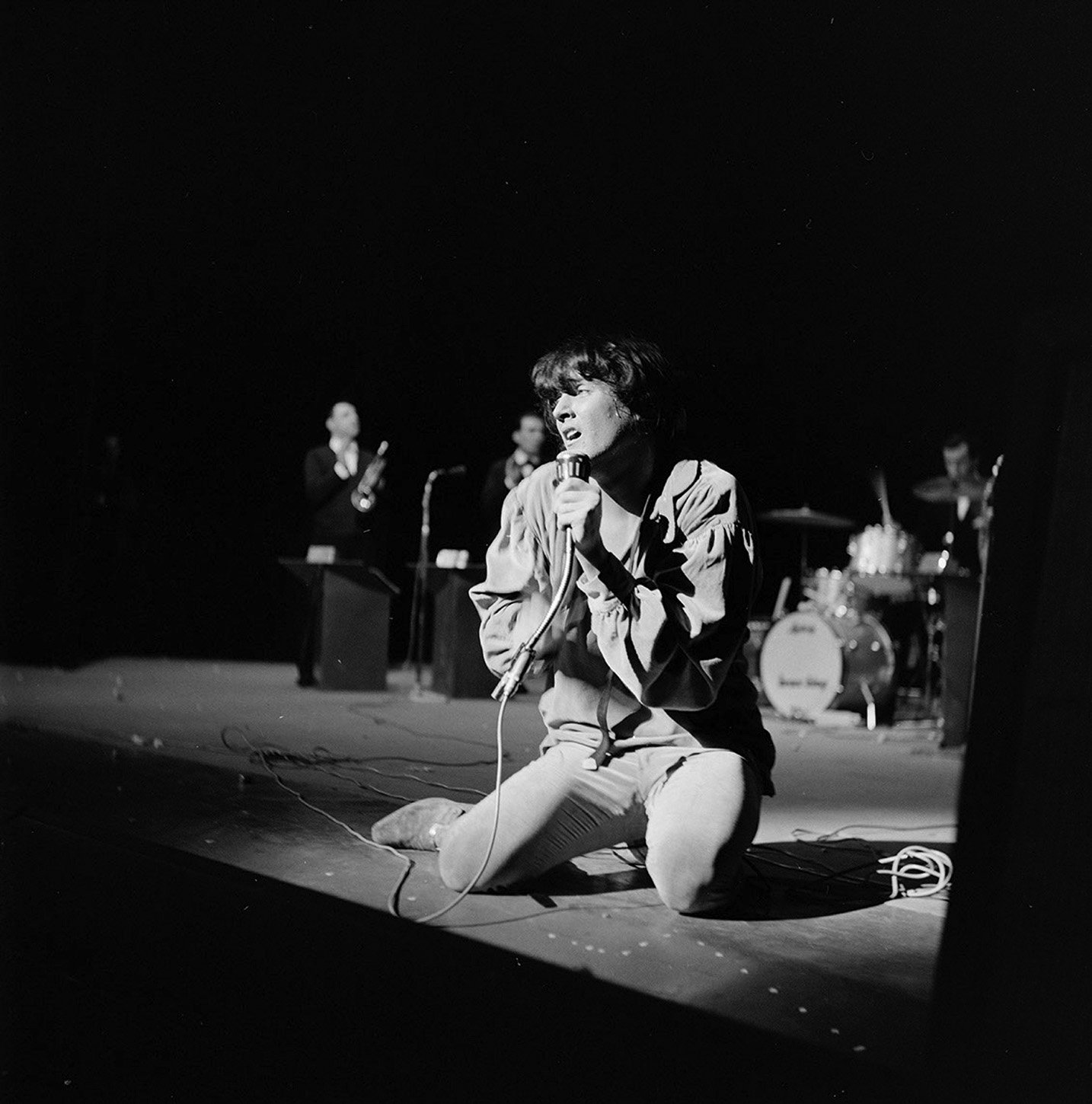

Figure 10.07: Barry Clothier: P J Proby, Wellington Opera House, September 1965. (ATL 35mm 37295-12). Courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library

Figure 10.08: John B Turner: Barry Clothier at Artides Gallery exhibition, Wellington, June 1965. (JBT A33-no number)

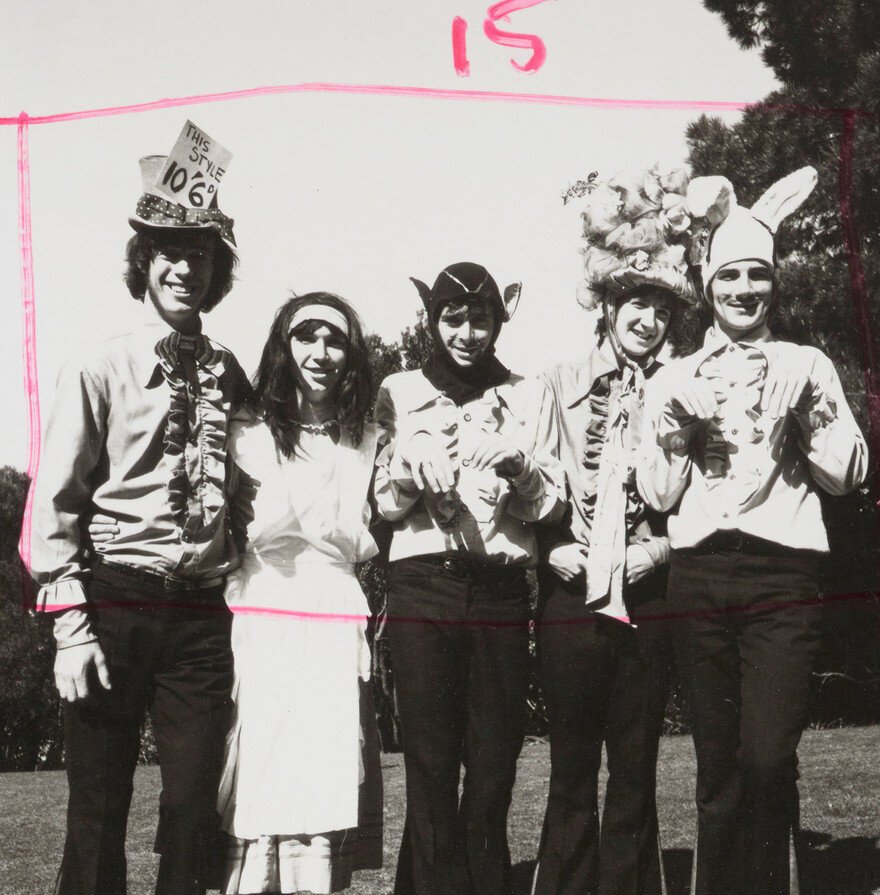

Figure 10.09: Barry Clothier: ‘Simple Image’ at Wellington Zoo, Grant Gillanders Collection, from AudioCulture website. Please note that the above image of the Simple Image band at Wellington Zoo may not be the exact version in the National Library of New Zealand’s catalogue description in Figure 7 below.

Figure 10.10: Barry Clothier ATL Screenshot Simple Image at Zoo (35mm-37663-1). Please note that the above image of The Simple Image band at Wellington Zoo may not be the exact version in the National Library of New Zealand’s catalogue description in Figure 9 above.

Figure 10.11: Barry Clothier: Detail from proof sheet of publicity shots of the band Simple Image, Wellington, May 1967. (ATL Ref. PAColl-7031-1-53). Courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library

Figure 10.12: Barry Clothier: Proof sheet of the Simple Image Musical group, 1967. (Screenshot 2021-05-09) Courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library

Figure 10.13: Barry Clothier: Fourmyula, 1967. Detail from proof sheet of publicity shots. (ATL-PAColl-7031-2-44.) Courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library

Figure 10.14: Barry Clothier: The Shevelles, July 1969. (Ref.-PAColl-7031-2-64). Courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library

Figure 10.15: Mark Beatty, ATL: The Turnbull Library’s Reading Room display of Barry Clothier’s photographs of the Wellington’s music scene in the 1960s. (ATL: 20210707_ATL_RRS_Simple_Image_009). Courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library

I couldn’t return to New Zealand from China to see the Wellington exhibition in person, so decided to review the exhibition as best I could from available sources, despite the gaps in my knowledge about the commercial and personal work Barry produced in the years between 1966 and 1971 when I moved to Auckland. Nevertheless, in response to a spontaneous request from Chris Bourke, a prolific historian of New Zealand music, on the day before the exhibition opened, I wrote a short item for his lively AudioCulture website about my impressions of Barry’s work as a photographer.

Barry Clothier and I lived in the Hutt Valley during the early 1960s and met at the Upper Hutt Camera Club in 1963 when he was 23 and I was not yet 20. He and his wife Judy later introduced me to Wendy, my first wife, whom they had both known from their Primary Teachers College days, and later our young children grew up together. Barry was working as a Post Office linesman when we first met, while I was an apprentice compositor at the Government Printing Office. He was a passionate musician, a bassist, and shared his love of jazz with me in return for my excited discoveries about historical and contemporary photography. Our exhibition at Artides Gallery in Wellington in June 1965 represented our movement away from the camera clubs toward trying out as professional photographers.

That was an exciting time for both of us when we tested our skills by photographing the performances of visiting international stars such as Shirley Bassey, Tom Jones, PJ Proby and The Dave Clark Five, as well as the up-and-coming locals Ray Columbus, Lew Pryme and others. Barry was about to leave his job as a post office linesman, and I had left my job as a compositor at the Government Printing Office to work as the photographic assistant for Dave Saché at the South Pacific Photos news agency, which syndicated work to a dozen regional newspapers from its base in the capital city.

After 1971, when my family shifted to Auckland for me to join Tom Hutchins and Max Oettli as a teacher in photography at the University of Auckland’s Elam School of Fine Arts, I saw Barry on fewer occasions over the years when he had his commercial photography studio in Wellington, and we gradually lost contact.

Figure 10.16: This is the first draft of the poster used for the Turnbull Library’s Reading Room display “The photography of Barry Clothier” of his photographs of Wellington’s music scene in the 1960s. The captions were deleted from the final design which was subsequently adapted for The Simple Image: the photography of Barry Clothier exhibition in the Te Puna Foundation Galley (see Figure 3). Courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library

Figure 10.17: Barry Clothier: The Selected Few, Botanic Gardens Wellington 1966. (Screenshot ATL 35mm-37400-00). Courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library

Figure 10.18: Barry Clothier: The Shevelles. (ATL 35mm 37690-00). Courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library

Figure 10.19: Barry Clothier: Jamaican pop-star Millie Small, 1966. Courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library

Figure 10.20: Barry Clothier: Fourmyula. (ATL 35mm 37747-00.) Courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library

Figure 10.21: Barry Clothier: The Avengers, 1966. (ATL Ref PA-Group-00671.) Courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library

Figure 10.22: Barry Clothier: Simple Image at HMV Studios, Wellington, 1967. Courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library

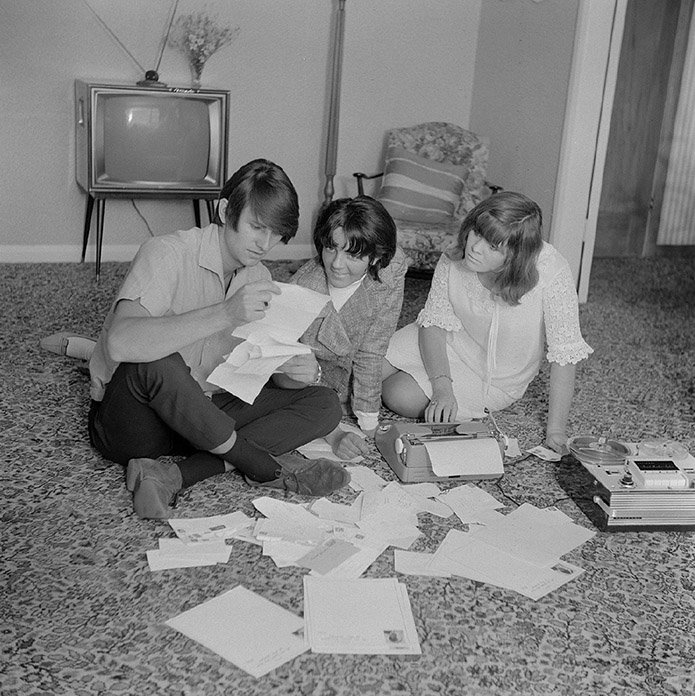

Figure 10.23: Barry Clothier: Mr Lee Grant with fans, 1967. (ATL 35mm 37484-08.) Courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library

Figure 10.24: Sal Criscillo: Entrance to Te Puna Foundation Gallery’s The Simple Image: photographs by Barry Clothier exhibition with cutout from Criscillo’s portrait of Barry “Bazza” Clothier, c1968. Courtesy of Sal Criscillo.

Figure 10.25: Sal Criscillo: Panorama view of The Simple Image: photographs by Barry Clothier exhibition in the Te Puna Foundation Gallery, NZ National Library, Wellington, 24 June 2021. Courtesy of Sal Criscillo.

Figure 10.26: Mark Beatty, ATL: Installation view of The Simple Image: photographs by Barry Clothier exhibition in the Te Puna Foundation Gallery, NZ National Library, Wellington, 16 June 2021. (ATL 20210616_ATL_RRS_Simple_Image_006.) Courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library

Figure 10.27: Sal Criscillo: Barry Clothier's proof sheet of publicity photographs for the band Avengers moving equipment and signing autographs, September 1968, displayed in The Simple Image: photographs by Barry Clothier exhibition in the Te Puna Foundation Gallery, NZ National Library, Wellington, June 2021. (Ref. PAColl-7031-2-42.) Courtesy of Sal Criscillo who wants it known that his were rough installation views, not professional shots (as were Chris Bourke’s), made at the request of John B Turner to gauge the form and content of the exhibition and received on 15 June 2021

Figure 10.28: Mark Beatty, ATL: Installation view from The Simple Image: photographs by Barry Clothier exhibition in the Te Puna Foundation Gallery, NZ National Library. (Ref. 20210707 ATL RRS Simple Image 005). Courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library

Figure 10.29: Mark Beatty, ATL: Enlarged images from Barry Clothier’s proof sheets exhibited in The Simple Image…. Te Puna Foundation Gallery, NZ National Library, 2021. (Ref. 20210707_ATL_RRS_Simple_Image_006.) Detail

Figure 10.30: Chris Bourke: Enlarged strip from Barry Clothier’s proof sheet of Lew Pryme publicity shots exhibited in The Simple Image…. Te Puna Foundation Gallery, NZ National Library, 2021. (Ref. Bourke 20210611_163040.) Detail

Figure 10.31: Mark Beatty, ATL: Enlarged details from Barry Clothier’s proof sheets exhibited in The Simple Image…. Te Puna Foundation Gallery, NZ National Library, 2021. (Ref. 20210707_ATL_RRS_Simple_Image_008.) Detail

Figure 10.32: Mark Beatty, ATL: Enlarged details from Barry Clothier’s proof sheets of ------- shots exhibited in The Simple Image…. Te Puna Foundation Gallery, NZ National Library, 2021. (Ref. 20210707 ATL_RRS_Simple_Image_002.) Detail

Figure 10.33: Mark Beatty, ATL: Enlarged strip from Barry Clothier’s proof sheet of The Chick’s C’mon Roadshow performance shots exhibited in The Simple Image…. Te Puna Foundation Gallery, NZ National Library, 2021. (Ref. 20210707_ATL_RRS_Simple_Image_004.) Detail

Figure 10.34: Chris Bourke: Enlarged details from Barry Clothier’s proof sheets exhibited in The Simple Image…. Te Puna Foundation Gallery, NZ National Library, 2021. (Ref. Bourke 20210611_163204.) Detail

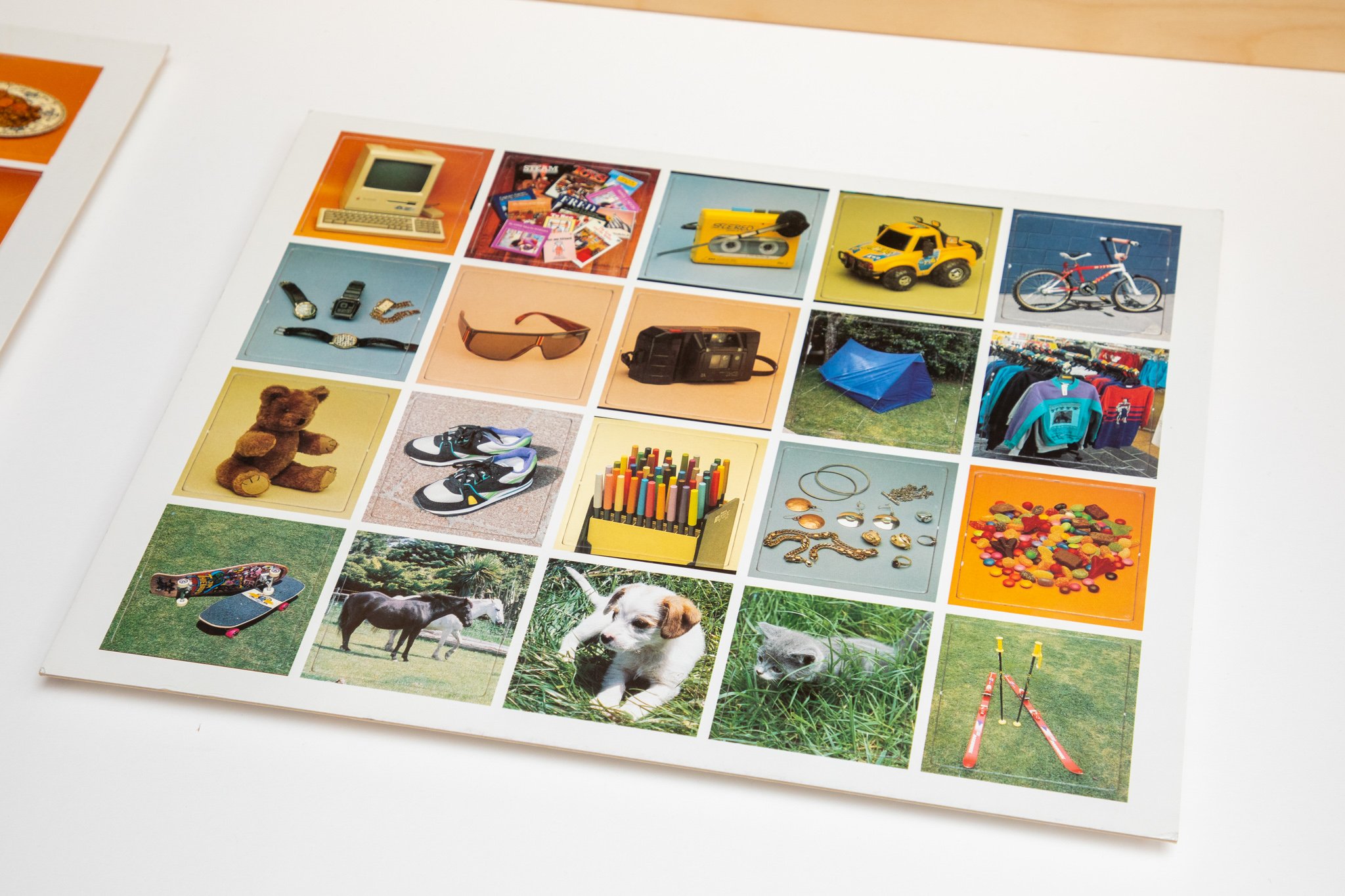

Figure 10.35: Mark Beatty, ATL: Display of photo-cards by Barry Clothier accompanying Kirikiti by Feaua’i Burgess, an Education resource kit for teachers. (ATL 20210616 RRS Simple Image 012.)

Figure10.36: Mark Beatty, ATL: Display of photo-cards by Barry Clothier accompanying Smokefree: Helping our Children to Remain Smokefree, an Education resource kit for teachers. (ATL 20210616 RRS Simple Image 011.)

Figure 10.37: Mark Beatty, ATL: Display of photo-cards by Barry Clothier accompanying Matariki: A Māori-Language Programme for Primary Schools, an Education resource kit for teachers. (ATL 20210616 RRS Simple Image 013.)

Figure 10.38: Mark Beatty, ATL: Display of photo-cards by Barry Clothier accompanying Matariki: A Māori-Language Programme for Primary Schools, an Education resource kit for teachers. (ATL 20210616 RRS Simple Image 014.)

Figure 10.39: Chris Bourke: Composite image of “Television clips and film” from Nga Taonga Sound and Vision collection, The Simple Image… exhibition, Te Puna Foundation Gallery, NZ National Library, 2021. (Ref. The Simple Image 20210611_163135)

Writing about an exhibition one hasn’t actually seen is a challenge, but being our National Library, I thought they would have on hand their own documentaton with installation views and publicity items to help anybody form reasonable observations and conclusions. The Turnbull Library’s photographer Mark Beatty kindly provided four detailed installation shots of the Clothier show to start with, but neither they, nor the few individual illustrations first included in AudioCulture’s feature about the exhibition, which coincided with NZ’s national Music Week, gave me an overall idea of its contents or form. What I could tell from the provided views was that there were three blowups of single marked images from Barry’s proof sheets next to one of my photographs of him on one wall and a poster-sized introductory wall label in a different position.

Obsessed with the need to get the overall picture of what was actually in the show (because the publicity made no mention of how many pictures were included, and I couldn’t see what they were), I found it difficult to believe, as the publicity implied, that the entire exhibition would be made of digital blowups from his proof sheets of musicians and bands rather than from his negatives in the Turnbull’s archive. Or that only work made for one music company would be presented.

After fretting over that, I scrutinised the small text of the wall poster shown in the installation shot and was delighted to see how readable it was. Next to my photograph of Barry changing film at our 1965 exhibition, there was a dislocated and unsourced quote from Barry plucked from our exhibition catalogue that “Photography is very underrated as a form of artistic expression”. The wall label continued:

The Simple Image. The Photography of Barry Clothier

“Musician and photographer Barry Glanville Clothier (or Clothface, as his bandmates sometimes called him) was born in Whangārei but moved to Wellington as a child. Although he initially trained as a teacher and worked as a linesman, he soon carved out a career as a professional photographer.

Clothier was also a keen jazz musician, playing bass with the Talbot Johnstone Quintet and part of a 1960s jazz scene that included the likes of Bruno Lawrence and Geoff Murphy.

Clothier’s connection with the Wellington music scene no doubt helped to kick-start his career in photography. The photographs displayed here include some of the most prominent Kiwi pop-stars of the day. He continued to work as an artistic and commercial photographer until his retirement, producing images for businesses, educational publications, and pet owners.

What are the markings on the photographs?

Many of these images include lines and arrows made with a permanent marker, as well as scuff marks and the occasional red sticker. This is because the images used in this exhibition are taken from Barry Clothier’s contact print proof sheets. A proof sheet is produced by developing [sic] a group of negatives on a single piece of paper, making it easier to select images to be enlarged and printed. Clothier made the markings on the proof sheets (perhaps in collaboration with the featured artist) to identify favourite images and demarcate crop lines.

We have chosen to keep these markings on the photographs to show the process of curation that was part of Clothier’s photographic work.”

I wasn’t involved in the music scene so don’t recall Barry being addressed with the believably perverse kiwi endearment of “Clothface”, but I do know that he liked to be called “Bazza,” the jazzier British slang term for Barry or Basil. The description of “developing a group of negatives on a single piece of paper”, however, was a clumsy and misleading description of printing, which is the correct term, especially coming from a library. And I was curious why the exhibition was called The Simple Image…., which punningly conflates the name of one of the bands he photographed with the content and form of Barry’s photographs as presented. Later it seemed to me that the title was meant as an in-joke for those in the know, as a sly evaluation of the photographs and music scene of the late 1960s as quaintly unsophisticated. (And if so, from a critical point of view, I would tend to agree with that point of view.)

Without seeing the actual exhibition, or hearing the curators’ floor talks, I am still not sure whether Matt Steidl and Malcom Duffy, from the Turnbull’s Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision section, had presented the exhibition, complete with contemporary video music clips from television sources, as a serious take or light hearted satire? There appear to have been no reports on what they said during their floor talks, although one assumes that curators don’t mock the work they labour to present, even when there is something to both admire and laugh about. Or if they do go for parody, that their position is made clear sooner or later, as was Peter Jackson’s brilliant spoof Forgotten Silver about an invented pioneer NZ filmmaker.

In my opinion, the sheer silliness of the embarrassing costumes and foolish antics performed for the camera were funny, even if they seemed less so at the time when The Beatles adopted new wardrobes and haircuts to stand out from the crowd. Barry Clothier was a follower of the fashion trends he depicted and, like so many photographers, embraced the theatrical tomfoolery of performance and visual experimentation like that shown in Chris Bourke’s feature on photography as performance art revealing a not so simple image, after all. It was business mixed with pleasure to be paid for getting to know and photograph new and established bands for leaders in the growing recording and publicity industry. Having a free hand to help other creatives to develop their own public persona was fun, even if there was occasional strife over which images were the best for a record cover or publicity. Every job presented opportunities to meet new people and learn the technical skills needed to make lasting images of the kind that inspired the desire to emulate one’s heroes.

Ironically, it was the lack of a rudimentary catalogue and sufficient illustrations from the Turnbull Library that caused my confusion and prevented me from completing my review. I had to ask for explanations to help figure out what exactly the exhibition of my late friend’s photographs consisted of when the sketchy PR notices combined with description of last minute changes to the final iteration of the exhibition confused, rather than helped the process of finding the missing parts of a shape-shifting jigsaw puzzle called The Simple Image.

The status of the Reading Room component, correctly described by Matt Steidl as a display and not an exhibition, continues to be confusing. As far as I could tell it was not mentioned in the publicity for The Simple Image, nor at its public opening in the Te Puna Foundation Gallery on 9 April 2021. Thus, as I eventually began to comprehend, the majority of exhibition visitors probably missed seeing the music industry images hung on the outside glass wall of the Reading Room. Consequently, my eyewitnesses were among those who missed what appear to have been the most faithful examples of Clothier’s work, consisting of enlargements made from digital copies of Clothier’s negatives, and possibly original prints as well. When Chris Bourke and Sal Criscillo (who I first met in the 1960s through Barry) both kindly revisited the Te Puna show to make installation shots for my exhibition review, they saw no reference to the Reading Room component and missed seeing it altogether.

Logic suggests that the nine reasonably well-chosen images in the Reading Room display should have been an integral part of the final exhibition if it was serious about showcasing Barry’s work. Just as keeping the display up for the rest of 2021 suggests that was the original intention. But nobody has explained why the posh new exhibition purporting to show how proof sheets work left the Cinderella display out of the picture in this litany of uncoordination.

Without installation views to guide me early on it proved impossible to make sound connections between the random gathering of images sourced from the publicity (notably AudioCulture’s lively coverage rather than the Library’s) and what the exhibition or exhibitions looked like. Until, that is, I later revisited a rough installation video kindly supplied by the Turnbull photographer Mark Beatty on the condition that it was “intended purely for reference not external display” and ended with the Reading Room display. That was my fault for not realising its importance in my confusion, but in the meantime the “use by” date had expired as far as a review was concerned.[i]

Here, based on the incomplete list provided (it does not include the token display of later colour images of different subjects of the kind that are the bread and butter of many commercial photographers, for example) is a rough combined list of images from the The Simple Image exhibition in the Turnbull’s Te Puna Gallery, plus the Reading Room display of undetermined status:

1. Barry Clothier (taken by John B Turner)

2. Simple Image

3. The Shevelles

4. Dinah Lee

5. Bruno Lawrence

6. The Fourmyla

7. Lew Pryme

8. Mr Lee Grant

9. The Falcons

10. Cheshire Kat

11. [Unknown audience]

12. Dinah Lee

13. [Unknown audience]

14. The Chicks (Live on stage, ( C’mon Roadshow)

15. Gerry Morito

16. The Bitter End

17. {TBC}

18. The Avengers

ATL Reading Room Display:

1. The Selected Few at Wellington Botanic Gardens, 1966

2. Jamaican pop-star Millie Small, 1966

3. Mr Lee Grant with fans, 1967

4. The Fourmyula, 1968

5. Simple image at HMV Studios, Wellington, 1967

6. American pop star PJ Proby on stage at the Wellington Opera House, 1965

7. The Avengers, 1966

8. The Gaynotes, 1968

9. W Rowles at the Wellington Botanic Gardens, 1969

Consequently, instead of a straightforward review of Barry Clothier’s photographs, my research morphed into a critique of the odd curatorship and presentation of work from his modest archive. I didn’t expect to see such an ambiguous and contrary example that would lead to question why, in fact, photographers should place their trust in the very collecting institutions that are presently making it more difficult for their work to be saved, by raising the bars of entry without consultation or discussion with the photographic communities involved.

Proof sheets

At first, I had trouble believing that the National Library, which had his original negatives, would opt to exhibit only enlarged digital prints made from Barry Clothier’s proof sheets (or contact sheets as they are also called) to represent his work. The stated reason “to inform viewers about the purpose of the proof sheet as part of the photographic process” in place of prints from his negatives became increasingly unconvincing as I was able to gather more evidence from various sources which revealed no attempt to demonstrate the multifaceted nature of the traditional proof sheet, let alone introduce a new digital era audience to the nature of other tools used by photographers to realise their vision. Neither was any attempt made to indicate the significance of choosing different camera formats and lenses; or the optical and emotional effects of film sensitivity and definition, or the effect of different photographic printing papers, and options open for printing for optical and emotional effect. The very differences, in other words, that argue for putting the negative and final print, not the proof sheet, at the centre of the creative process.[iii]

(For those who don’t know, proof sheets were/are made by laying strips of roll film negatives under glass in direct contact with the photosensitive paper they were printed on, which means that the images are the same size as the negatives. Proof sheets are a valuable learning and editing tool because they reveal so much about the photographer’s ideas, intentions and working methods - including evidence of missed opportunities and blunders - which was one reason why photographers avoided showing them to their perceived rivals).

Among the attributes of the analogue proof sheet is that it naturally functions as a visual diary by displaying image by image the sequence in which each exposure was made. And providing they and the negatives are sensibly numbered and dated they provide vital information for filing, cataloguing and retrieval purposes. (See Gael Newton’s description of David Moore’s collection for a positive example, compared with the idiosyncratic chaos of Max Oettli’s old filing system, given as examples in this blog series.) As the casual nod given in the Turnbull’s exhibition hints, the proof sheet is often used as a notebook as well, with personalised marking systems to indicate which images seem promising enough to take further. Some photographers habitually make “work prints” (usually small rough versions) to contemplate before attempting to make final prints. And some, depending on the pressure of time and/or confidence in a particular image, don’t bother and proceed to making final prints to capture what they saw and felt. Ansel Adams, the virtuoso US photographer who was formerly a concert pianist, aptly described the analogue negative as the score and the print as the performance.

It is important to realise that the photographer’s marks on their proof sheets, which feature so prominently in this exhibition, need to be seen in context. They are not conclusive evidence of either being printed at all, let alone cropped as indicated. The marks represent indications of a tentative possibility for serious printing, rather than reflect critical acceptance of them as final works worthy of public exposure.

Thus, another opportunity to educate as well as entertain was lost when all that was needed was to display existing samples from the Clothier archive to indicate the basic differences between analogue, “born digital” and hybrid photographs. Simply displaying a genuine vintage print from the 1960s next to a high-quality new digital print made directly from a copy of the original negative could have made that point. Just as could displaying a sample work print, and/or an original Clothier proof sheet next to its bigger, different, but not necessarily better digital cousins demonstrate the difference between analogue and digital methods used to edit, make and display photographs.

Or in response to one of Prof Geoffrey Batchen’s hints to Te Papa, discussed previously, why not display an actual film negative compared to a Peter Robinson-like picture of the unique combination of ones and noughts behind the digital pixels, to conclude the narrative and make it real?

Optically, the difference between an enlarged digital copy from a photographer’s contact print and similarly enlarged gelatin silver print made from the original negative can be compared with the difference between reading with and without reading glasses, because essential detail is lost, as it also is when an enlarged digital image explodes into pixels and refuses to yield further information.

Likewise, any direct comparison of a digital print made from scanning the negative, vis-à-vis scanning and enlarging from a contact print, is bound to demonstrate the optical superiority of the former, because a negative (or transparency) can record a tonal scale (contrast range) of about five times more than the most luscious print, which when closely examined reveals the texture of the paper, if not the grain of the film as well . Nevertheless, it makes sense that the inclusion of some contact sheets and enlarged contact prints could be valuable as informative as well as decorative elements in an exhibition. But whether the photographer would have approved of third-generation copies becoming the sole representation of his work is dubious when his precious negatives were selected for the Library to make new prints from as and if desired. That would be akin to a musician perversely opting to have only inferior recordings represent their legacy.[iii]

Ultimately, like Geoffrey Batchen’s reminder that cost-cutting and inadequate planning from top management were partly to blame for Te Papa’s lapses of quality control, so too it appears that the trajectory of this curious example; an innovative but inadvertently rogue exhibition produced by our National Library, was afflicted by a similar lack of curatorial support and coordination.

Perhaps the problems revealed in the making and presentation of The Simple Image: The photography of Barry Clothier best stand as a warning that however photographers usually edit and promote their own work, future interested parties may not perceive it in the same light. And if so, that is not necessarily a bad thing because it seems to me that the promise of curatorial insights outweighs the risk of once-in-a-blue-moon disasters that can easily be criticised. The most important issue is to ensure that the process of decision-making and presentation is transparent and critically sound. There is nothing inherently wrong with attempting to present pop industry photographs with a light-hearted touch in keeping with the youth-oriented content of much of the imagery and pop music itself. But if so, it should be declared as such, instead of pretending it is a serious overview of a photographer’s legacy.

Curating, after all, is a creative process which fails if it doesn’t challenge preconceptions and enlighten its audience. My search for hard facts about the Clothier exhibition left me flabbergasted and frustrated from beginning to end because the library, of all places, had made so little effort to document its existence, there being no catalogue or descriptive information to share with interested parties.

Asked about the history of this exhibition, Matt Steindl explained that he had formulated the idea for an exhibition of Barry’s photographs while working in his previous role as Music Research Librarian (2011-2017) at the Alexander Turnbull Library and the opportunity to develop the idea arose when he became the Team Leader of the Turnbull’s Research Enquiries team in 2017.

“Last year [2020] I started working on a modest display of Barry’s photographs for a small glass display area in the ATL shifting [?] Rooms (level 1), however as I was about to install this small display, the opportunity arose to expand it from a display to a slightly larger exhibition hosted in the Te Puna Foundation Gallery (also in the Library on the Ground Floor). I took this opportunity to complement the photographic works with some A/V footage of the featured musicians. For this I approached Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision and began working with Malcom Duffy to select appropriate video content …. [so] I consider it a co-curation by myself and Malcom.”

Matt’s description of how the new iteration, called The Simple Image… “exhibition” came about and how it related to the ATL Reading Room “display” was ambiguous; implying that they were parts of the same exhibition but not explaining why there was no signage at either site to make that intended connection. The design of the Te Puna Foundation component was obviously tailored to fit into its restrictive architectural features, but whether the design cosmetics hid the failure of the exhibition’s content to live up to its stated aims is another issue. (See Postscript below)

The online catalogue

How does a library record a photographer’s collection over all? And what does the NZ National Library’s record of a particular image record? When I searched the Library’s online catalogue entries for the details of Barry Clothier’s gift, I was very surprised to find vague and inaccurate descriptions of its scope and content that reminded me of the days when untrained volunteers were tasked with compiling handwritten catalogue entries on cardboard index cards.

According to their catalogue description (See Figure 10.05 above) under “Quantity” the donation consisted of:

“556 b&w original negative(s) with 1901 images. 132 original photographic print(s) contact sheets of a variety of music groups he photographed between 1965 and 1995.”

The description of “556 negative(s) with 1901 images” is patently ambiguous. Do they mean 556 strips of negative film with more than one image per strip, totaling 1,901 individual images? That’s not at all clear. Roll films are commonly cut up into convenient strips of three or four exposures on 120mm film for filing and contact printing, while 35mm negative rolls are usually cut as strips of five or six exposures for the same purpose. (It’s one of the minor miracles of photographic technology that both twelve 120mm and thirty-six 35mm images fit perfectly on a standard 8 x 10 inch (20 x 25cm) sheet of photographic paper).

The description of “132 original photographic print(s) contact sheets” is also ambiguous. Does it mean just contact sheets, or a mix of individual prints and contact sheets, and/or cut up segments from them? (Some photographers prefer to cut out each frame and eliminate failures before making their truncated proof sheets, for example, and store each frame in its own protective envelope. Some clump all of the strips in one envelope, and others store their uncut rolls curled up. I don’t know if picture librarian-cataloguers are given any practical classes in analogue or digital photography, but that could be a useful part of their training).

The online catalogue description of a single image for quantity was recorded as:

“1 b&w original negative(s) individual images on strip of 120 [mm] film”.

That is reasonably understood jargon, but once again does not clarify whether the negative is one of three exposures on one strip, or equally possible: one image on one of four three-image strips from a full 120mm roll of film with 12 individual 120 x 120 mm exposures? The answer depends on whether a single frame, if cut from a film, is counted as a strip or not? And that question can be easily solved when a clear image of the negatives and/or a proof sheet is sighted. Perhaps I shouldn’t worry, but while I am in my pedantic cataloguing mode, I shall note that as well as the possibility of using longer 120mm rolls for twice as many square exposures, some camera formats proffer the choice of making more than a dozen smaller rectangular images on the traditional 12 exposure length of film.

The Library’s image reference system also causes confusion because it tags a wholly square and clearly non-35mm format image as “Ref. ‘35mm-37663-1.” But, as the librarians know, that does not indicate the format of the original negative but is inhouse code meaning that the negative (or a print from it of any shape or proportions) was copied not by direct digital scanning, but with a 35mm digital camera for their catalogue, accession records and future purposes. And being a digital file, the godsend of accurate duplication of a negative image with reversed tones and colours, it is merely a mouse click away from being transformed into a multi-purpose positive digital file that can be used for printing and/or online display such as ours.

To their credit, when I pointed out these ambiguities, the Library quickly responded by changing their description to “556 b&w original negative(s) strips comprising 1901 images. 132 b&w original photographic print(s) contact sheets.” Where the examples of Clothier’s late career run-of-the-mill commercial colour photographs presented in a display case (as revealed in the Bourke and Criscillo installation views) fit in, however, is a new mystery about how accurate a catalogue needs to be.

Dare I ask why the copyright to these pictures is stated as “Unknown”? Is it a universal code for “Don’t ask us to go down that rabbit hole” because the donor did not specifically address the horrible complication of attributing legal ownership to each and every image, when some were taken for paying clients and others for personal reasons of all kinds. As justified and supportive as it might be to some owners of “intellectual property”, that grey land of lawfare is a minefield (a pun just noticed) between fear, fair and unfair use. Certainly, any confusion over ownership can stymie the use of images for non-commercial and educational purposes, for example.

Rather than not paying the owner in cash, the greater sin, to my mind, is not to credit both the author and source of an image. Information that is important not just as a courtesy but allows conscientious requests for permission to be made, and questions asked about its material dimensions, technical process and provenance that provide essential information for scholarly research. The absence of such details provided with online discoveries simply creates frustration and confusion.

The Clothier photograph (or a close variant) of a promotional image of The Simple Image band at the zoo (Figure 07) sourced from Audio Culture is typical of those usefully and accurately described with attention paid to identify the people in the photograph. It is a reminder that minimal information from the practitioner is preferable to none, and any further detail, such a mentioning if it was ever published or exhibited would be a bonus for researchers.

Commentary on the promos and text

It is always disappointing to see a well-meaning concept undermined by inadequate research, poor delivery, or glib publicity when it had the potential to be a model of its kind for inciting a new audience to take notice of the subject in question. I have little idea of how well the sound and video components presented by these music experts might have worked with the photographs on display that I did not personally experience and can only hope they accurately evoked something of the Wellington music scene of the 1960s.

I would, however, like to question the accuracy of some of the glib PR statements, such as this announcement of a joint floor talk to be given by the curators on 25 May 2021:

“In the 1960s, Wellington jazz musician and photographer Barry Clothier was ‘photographer to the stars’, and anyone who was anyone in the local pop scene commissioned a photoshoot with him.”

“Drawn from Barry Clothier’s personal archives held at the Alexander Turnbull Library, The Simple Image features rarely seen photos of Kiwi icons, including Bruno Lawrence, Maria Dallas, Dinah Lee, The Chicks, and many others.”

“Exhibition curators Matt Steindl [Team Leader of Research Enquires at the Alexander Turnbull Library], and Malcom Duffy [Customer Supply Advisor at Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision] will speak about the work of Barry Clothier, discuss the process of exhibition design and highlight some of their favourite pieces.”

While it might not be too gross to affix the cliché of “photographer to the stars” (aka, the bigger fish in a small pond), the claim that “anyone who was anyone in the local pop scene commissioned a photoshoot with him” does not ring true and I doubt that Barry would have claimed that then or now, were he still alive.

It’s invaluable to be reminded that New Zealand’s small but vibrant music scene has a fascinating history all of its own, and its own Who’s Who? from the 1960s when Elvis Presley, the Beatles, and other music legends reigned supreme. And as our music historians like Chris Bourke remind us there is a wealth of insightful performance photographs made by accomplished photographers in New Zealand.

Compared to the music scene photographs of his friend Sal Criscillo, and the work of later practitioners such as Murray Cammick and Anthony Phelps, Barry Clothier’s work looks rather tame, as do the great majority of photographs representing this sub-culture. The still-assumed glamour of working as a “Music Photographer” (a delightful contradiction in terms) is well captured by Jeremy Templar’s 2021 feature So You Wanna Be A Music Photographer?

Yes, Barry took early photographs of those among the best-known names today: Bruno Lawrence and Geoff Murphy among his friends, and Maria Dallas, Dinah Lee, and The Chicks, but few of his images of these “stars” can be counted among the most successful of his photographs, whether published or not at the time.

Ultimately, although Barry may not prove to be a major figure in either the history of popular music or the history of photography in New Zealand, his work certainly offers insights into our cultural history. That, presumably, was the reason for the National Library to adopt this work in the first place. Its use value is in its ability to introduce or jog our collective memory about our 1960s music scene through his photographic coverage. And while the idea of coupling his photographs taken for the purpose of commercial promotion with film and television clips from the end of the pre-video era as cultural artifacts was innovative and potentially exciting, its dubious realisation appears to have made it more of a lost opportunity than an inspiration.

Collecting institutions are demanding photographers provide more detailed annotated and catalogued information about their work than was expected in the past, before their collection will even be considered for inclusion. Thus, there is a corresponding need for many accomplished photographers who perhaps vainly assumed that their pictures said it all, to be coached in how to describe the content and form of their images with as much clarity as they can provide for our picture archives.

Were it not for May being designated ‘New Zealand Music Month’, and AudioCulture’s promotion related to its sponsorship of a new prize for performance photography to be offered by the Auckland Festival of Photography, practically nothing would have been heard of this exhibition. Sadly, that casts doubt on the National Library’s commitment to meaningful exhibitions and sends a less than friendly message to photographers seriously contemplating our National Library as a potential home for their work.

Authentic collaboration between expert picture librarians and photographers is vital to instill confidence in the fraught collection exchange process. Sound, practical advice in the spirit of mutual respect needs to be provided to ensure successful outcomes from the complex process involved to demonstrate that the photographer’s intentions and the work and themes they want to be remembered by is recognised, as is the recipient institution’s responsibility for independent critical evaluation of the work in question.

But whether the powers-that-be will acknowledge, let alone support this and other urgent initiatives with targeted funding to prevent disastrous gaps in the photographic record of our cultural heritage is another issue that should concern all New Zealanders.

***

Postscript:

In his 1 March 2022 response to my draft of this commentary Matt Steindl stressed that:

“the display/exhibition was never intended a photographic exhibition, but rather as an exhibition/display of photographs if that distinction makes sense. In as much as it was intended primarily to be about the music & social scene (which I do know a little about) rather than about the photography (which as you point out, I know pretty much nothing). I realise now (in fact I realised it earlier, but by then the signage was all printed) my big mistake was in the subtitle (The photography of Barry Clothier) which justifiably may have led some to believe it was intended as some kind of retrospective photography exhibition. Far from it. The library only holds the one collection of Barry’s photographs to draw from, and I had neither the means, time or expertise to source loans from other people/institutions.

What I should have called the subtitle was “featuring the photography of Barry Clothier that is held at the Alexander Turnbull Library”. Not an especially snappy title, but at least it would not have been misleading… “

Further elaboration on the genesis of the display/exhibition:

“I had spent some time with the collection of Barry’s photographic negatives in the course of my role as the Music Research Librarian. It was one of my favourite collections in the Library for a few reasons: it consisted of (great!) photos of an era of NZ music/society that I’m interested in; it was a largely unknown collection due to not having been developed or digitised; and I was intrigued by Barry Clothier as few people I’d met knew of him, and information was difficult to find.

The Library does have a dedicated exhibitions team (of 2) who oversee & support the various exhibitions installed in the different galleries the Library. They run an on-going proposals process whereby staff and external curators propose exhibitions (usually, but not always, drawing on the Library collections) and a panel selects the successful ones. Recently a small display area came available in the Alexander Turnbull Library Reading Room and I had it converted to a space for displaying flat images. This is very much a “display” space, rather than an exhibition space – in that at most it fits 9 small (50 x 50cm) images – very much in the “Library display” tradition (and by that I mean - a display of interesting items, but without any particular critical analysis). Because this was just a small display space it didn’t really fall into the purview of the exhibitions team in terms of quality control or support.

Anyhow, I had selected a small collection of Barry’s photographs from the collection we hold to put in the display case for 1 year. The only supporting critical analysis was the basic (original square) panel I designed myself just to say who Barry was and what the photographs were.

Shortly before installing these however, the exhibitions team proposed that I move the display to the larger Te Puna Foundation gallery, as it had unexpectedly found itself empty for 2 months, and the thinking was that it was better to put something in there rather than nothing. So at very short notice this entailed expanding the scope of the exhibition to fill the space, which was primarily done by collaborating with Ngā Taonga, and including what few examples I could find of some of Barry’s later work (taken from published books). There was neither time nor money to expand the research or analysis required had it been designed for this space from the get-go.”

A full explanation about the long process of creating the display/exhibition would be boring, he hinted, partly due to having it in different parts of the Library:

“[We had to] chip in here and there after I said that I couldn’t move it to the larger gallery without a bit of extra $$. But I also was able to find in my own budget, in the following financial year, enough to also proceed with the Reading Room display as it was intended. But because of the financial year cycle of Govt departments this wasn’t certain until after the Te Puna component had been installed – hence the lack of connections. See what I mean about boring!”

So the exhibition was installed in the Te Puna foundation gallery. The use of the contact sheets rather than the negatives was my idea, again because that was the angle that I was interested in (showing the behind the scenes workings of both the musicians and photographer), rather than showcasing the format of photography as a medium. Again though, the intention was always to have a mixture of images printed both from contact sheets and from negatives, but not from a particular interest in photographic process, but rather a behind-the-scenes and in-front-of-the scenes perspective.

Anyway, in summary I’d just say that I think being critical of the exhibition as ‘a photographic exhibition’ is a bit like shooting fish in a barrel, as it was never intended as such, although I acknowledge I made a misleading mistake subtitling it as I did.

As an exhibition of a particular historical collection of images by Barry Clothier of a particular time and place, I still stand by it 100%.”

Barry Clothier’s and John Turner’s exhibition at Artides Gallery, Wellington in 1965

A not so flash flashback

Figure 10.40: Clothier-Turner exhibition poster, Artides Gallery, Wellington June 1965. Turner collection

Acutely aware of the failure of the National Library to provide basic documentation on The Simple Image… it was easy to spot similar problems with my installation shots and our catalogue when Barry Clothier and I shared an exhibition at Artides Gallery 56 years ago. This despite our good intention to provide a basic takeaway guide to our images and thinking.

One of my yardsticks for analysing historical and contemporary photographs is to ask what is their use value? By which I would ask how much use would a picture have in say 100 years to inform future generations about an aspect of life in the place the picture was made? Alfred H Burton’s 1885 photograph of the village of Koroniti on the Whanganui River, for example (Figure 10.41 below) has high use value because it captures the look of a Māori community in transition, with housing made of both traditional and new Pakeha materials. It is rich in information in many respects upon inspection and at the same time indicates something not only of the colonial photographer’s attitude towards the subject matter but also what the audience/client’s interests might be.

Figure 10.41: Alfred H Burton: BB3513 Koroniti (Corinth) Wanganui River, 1885. An example of the extreme difference of definition and detail available from a typical online thumbnail representation and the actual detail that can be seen from a high-resolution scan from an original negative or a print made from it. Courtesy Whanganui Regional Museum and Te Papa respectively. (See also Part 5 for more commentary on this image.)

I don’t recall where I first picked up the phrase “use value” but now see from Wikipedia that:

Use Value (German: Gebrauchswert) or value in use is a concept in classical political economy and Marxian economics. It refers to the tangible features of a commodity (a tradeable object) which can satisfy some human requirement, want, or need, or which serves a useful purpose. In Karl Marx's critique of political economy, any product has a labor-value and a use-value, and if it is traded as a commodity in markets, it additionally has an exchange value, most often expressed as a money-price.

I was thinking not about the money-price of old photographs, except in the sense that they can be priceless for capturing an idea or experience or place at a special time in an insightful and perhaps unique manner. That’s what makes them valuable and useful. Think of Dorothea Lange’s photographs of the ‘Migrant Mother’ (Florence Thompson and her children) 1937, or John Thomson’s photographs of China in the 1870s. Think of Ans Westra’s and John Miller’s documentation of Māori society in New Zealand. Think of Bruce Connew’s essay on coal mining and David Cook’s record of Rotowaro, the Waikato mining town that was completely razed to make way for an opencast mine.

There are many more outstanding examples that can be given, and I would not include my record of the Clothier/Turner photo exhibition among them. Rather, by showing its content and form here, I give it as an example not only as a background to Barry’s earlier photographs (and mine by association and as a living witness) but also for the reader to decide whether it should be deemed sufficiently significant for our National Library to add to its archive? I know, for example, that the Auckland War Memorial Museum specifically lists among their major themes the “History of photography (Auckland photographers, New Zealand photographers)”, and whether stated or not a few librarians have done a superb job of recording the biographical details of a considerable number of photographers represented in their collections who would otherwise be invisible record keepers. Speaking of which, many librarians are invisible chroniclers unless encouraged to write or otherwise present their research and insights to the public.

Simply put, I present this case as just one example of one kind of record (that of a mid-1960 exhibition) which was dismissed by a library professional as a possible addition to the Turnbull’s collection. There was no attempt to sound out colleagues for their opinion – just disinterest. It’s a sad old story, of a potential donor being brushed off without serious consideration by somebody expected to be a trustworthy authority or conduit to experts able to assess possible treasures with detached respect. And it reminds me that my first encounter with this phenomenon occurred in the mid-1960s when I discovered that the widow of “Zak” Joseph Zacharia, a prominent Wellington photographer, was so disheartened by the lack of interest shown by a Turnbull librarian that she sent all of her husband’s negatives to the Karori Tip the week before I visited her. (See Part One of this blog series.)

I suspect that such casual dismissals are relatively common and are indicative of a widespread lapse in coordinated quality control, training, and professional ethos. An abrogation of responsibility, whether through ignorance or design, by the nominal leaders of organisations charged with the difficult task of ensuring the preservation of our diverse cultural treasures.

This concept of use-value, or practical use, in relation to historical evidence – as against the less obvious practical value of much art – is central to the crisis now facing photographers as to whether all or part of their life’s work should go to an archive or the dump.

Libraries are now virtually insisting that photographers curate their own collections before they will consider adopting bodies of work for the historical record and public good. That’s a risky business not least because most practitioners, understandably, are likely to favour what they see as their “best” images, while the picture librarian is more likely to choose images that will supplement or reinforce their collecting interests, rather than echo material they already have. Close collaboration is required to discuss and resolve the inevitable differences of perception as to whether the selectors are acting as caretakers or undertakers for certain batches of images. But with our libraries signalling that they are under-resourced, understaffed and out of space (the reasons given for insisting that practitioners initially cull their own collections) there is little evidence of our libraries reaching out to identify and assist our finest (and now elderly) documentary photographers with significant analogue collections.

As previously mentioned, it’s about a decade since two accomplished photographers sought my views on how best to ensure that their work could be preserved for posterity, and which public library, museum or gallery would be best to approach? As a former museum photographer, it was not a new issue for me to consider, and I am proud of my behind-the-scenes success in helping to find suitable homes for photographs by Ans Westra, Eric Lee-Johnson, and G Leslie Adkin among others in the past.

Today, I’m particularly concerned about what is not happening to ensure the collection and preservation of the photographs of my fellow post-World War II generation who have so much of their life’s work invested in large collections of analogue negatives and prints. This article is part of an ongoing investigation of this crisis not only from the points of view of involved librarians, archivists, institutions, and photographers, but also historians and art scholars.

The time has certainly come for photographers to seriously devote time and thought to what they imagine their legacy is in terms of communication and expression (art) in New Zealand photography, and how they can best convince our social history and art archives to adopt all or parts of their most valued work. Which comes down to selecting an undefined number of negatives, transparencies, prints and/or digital representations worth preserving for posterity, and self-censoring the rest. Perhaps the wealthier among us could afford to build their own private temperature-controlled image bunker, or hire their own curators, but if so, that is not the same as having one’s work preserved in a national or regional archive dedicated to preserving and giving public access to one’s work.

How do librarians, curators and archivists decide which collections to investigate? How do they attribute significance? (That question is the particular focus of Part 3 but is central to every aspect of this investigation, of course.)