NEW ZEALAND’S PHOTO TREASURES HEADING FOR THE TIP? - Part 3

Notes on the collection of photographers’ collections for posterity

A PhotoForum discussion paper by John B Turner

Part 3: Significance, and Archives for Artists

“Having to be more articulate and critical about the content and context of our life’s work is a sobering experience, as it is to start to realise that we may have to give up any assumption that future generations will have any interest whatsoever in how we individually responded to our world with a camera”.

01: Introduction

02: Te Papa

03: Significance, & Archives for Artists

04: Gael Newton: Parting with your art & Photographers’ Archives

05: Auckland Art Gallery & Alexander Turnbull Library

06: Auckland War Memorial Museum & Auckland Libraries

07: Internal Affairs & Heritage Departments

08: Canterbury Museum & Christchurch Art Gallery

09: Collection case studies: Tom Hutchins, Paul Gilbert, Max Oettli & Barry Myers

10: Curating, Barry Clothier Simple Image show & Clothier/Turner 1965 Artides show

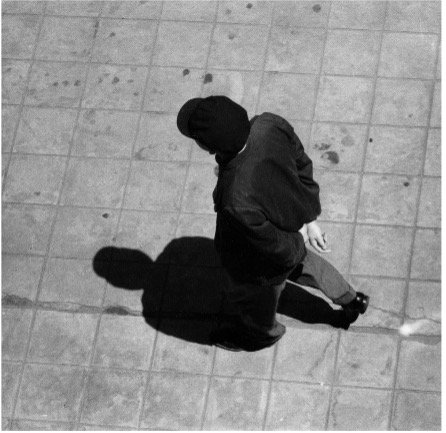

Are these significant historical photographs?

Works of art?

Both, or neither?

That is what specialist picture librarians, curators, archivists, and historians are

called upon to decide every day

Please consider the primary criteria:

Historic, Artistic or aesthetic, and Social or spiritual when assessing significance

There is no prize for deciding which of these images might be significant or have some use value,

because they are presented without identification, provenance or context.

Click here for information about them [i]

SIGNIFICANCE

Who has the say?

Almost everything to do with whether a collection is saved or destroyed depends on its perceived significance. So, who decides and on what basis is important. We must ask for whom, and what purpose they are deemed significant enough to go into a public or private archive?

It does not deal much with photographic collections as such, but there is a useful book devoted entirely to this subject published by the Collections Council of Australia Ltd, in 2009: Significance 2.0: a guide to assessing the significance of collections, by Roslyn Russell and Kylie Winkworth. The authors identify four primary criteria to apply when assessing significance: Historic, Artistic or aesthetic, Scientific or research potential, Social or spiritual.

As Noel Turnbull, Chair of the Collections Council of Australia council emphasizes in his foreword to the guide, it is impossible to keep everything forever, and ‘significance is not an absolute state – rather, it is relative, contingent and dynamic. Views on significance depend on perspective and can change over time.’ He reminds us that power is wielded in constructing societal memory and identity, and that ‘collection custodians therefore have a responsibility to consult affected communities and to be hospitable to alternative views in recognition of the fact that significant decisions inevitably privilege some memories and marginalize or exclude others.’ (It is perhaps worth bearing when one makes a case for saving a collection, that understandably, some collecting institutions might fear to reach out to the photographic community for their suggestions and support because they can’t deal properly with their present backload.) ‘When assessing significance,’ Turnbull adds, ‘it is vital to understand, respect and document the context of collection materials-the events, activities, phenomena, places. Relationships, people, organisations and functions that shape collection materials.’

While this general guide for the professionals responsible for assessing the significance of collections does not deal with photographs specifically in any detail, it does emphasise that significance is a proven persuader. Society might think that a Colin McCahon painting is worth 1,000 photographs, but to persuade it otherwise, photographers need to put more effort into explaining the significance of their work.

‘Whether it’s making the case for a new acquisition, substantiating a funding application, or lobbying for education and online resources, significance goes to the heart of why collections are important and why they should be supported.’ [ii]

Here are the essentials for considering ‘significance assessment’:

· Analysing an item or collection

· Researching its history, provenance and context

· Comparison with similar items

· Understanding its values in reference to the criteria

· Summarizing its meanings and values in a statement of significance

‘At a simple level, significance is a way of telling compelling stories about items and collections, explaining why they are important.’ Anybody who has ever filled in an arts council award application or submitted a reference in support of a project will recognise the similarity to these five basic points of significance assessment.

In addition to these qualifiers there are four important modifiers of the main criteria used to evaluate the comparative degree of significance, in relation to their own collections, thay are Provenance, Rarity of representativeness, Condition or completeness, and Interpretive capacity

It is not necessary to find evidence of all criteria to justify that an item is significant... an item may be highly significant under only one primary criterion, with clarification added by considering the comparative criteria’ the guide states. But while provenance, where you are the single author and source is easy to determine, for example, it’s up to the gods to decide your status among your peers and the rarity and interpretative capacity of your work. It’s well worth musing on the condition of your collection and its level of completeness as well. Despite the likely need to cull it if, as Athol McCredie cited, there are too many duplicates or less significant lookalikes, the actual (physical) condition of one’s work is something well within your control and responsibility and attention to it could be the point of difference between whether or not it is adopted by a collecting institution. [See the case history on Tom Hutchins’ collection in Part 9.]

As Russell and Winkworth acknowledge:

Every day, collecting organisations are making judgements about which items and collections will be collected… These are profound decisions that shape what future generations will know and understand about the past and present.

Striving to be objective and practical, by using a consistent process and criteria, the authors of Significance 2.0… are firm advocates for the value of written statements of significance (something akin to the references sought for an arts council application, perhaps) based on the criteria they have outlined, from both the source of items and the potential recipient.

They recommend that collections always ask and consider to whom the item or collection is significant? And wherever possible, to get the donor or community to describe, in their own words, ‘why an item or collection is important to them…’. Significance is not a value judgement, they claim, while acknowledging that there will always be an element of personal judgement and enthusiasm [or not]. The need, which they supply, is for a consistent process and criteria that nevertheless allows for extenuating circumstances through rigorous and well substantiated assessments. At their best, they say, statements of significance should combine logic, passion and insight. In a case of conflicting opinions, they advise that the statement of significance can [should] reflect the nature and substance of multiple points of view.

If it goes without saying that one is expected to place one’s trust in the qualifications and expertise of the people who make the decisions and the fairness and wisdom of their deliberations, little effort seems to have been made in regard to the transparency of their deliberations.

While they barely touch on issues relating to a photographer’s collection, many of their points and recommendations still apply. Such as the point that collecting organisations have several options including the single item assessment method, or might assess particular themes or a section of a collection, rather than take a whole collection. In either case, they recommend focusing on the most important items in the collection and seeking more information on it before those who remember it age and die.

Regarding how significance relates to the financial value of an object, they conclude that while the monetary value of an object often reflects significance, that financial value is not a significant assessment criterion: that a significant item can still be of limited monetary value, and similarly, that many valuable items are of limited significance for public collections.

They do not touch on the possibility of what would essentially be censorship in regard to the nature of work that might explicitly deal with issues such as drug use, personal erotica and sexual practice, or evidence of violent or illegal activities, let alone the secret lives of corporations, and public institutions such as the police, courts and prison life. The kind of gritty real life subject matter that serious photographers might pursue but is rarely, if ever, seen in our public archives. It’s not difficult to imagine a committee tut-tutting over such content and deciding it is too hot to handle and thereby eliminating the visual evidence from our historic and artistic records. If so, as I strongly suspect, that blindness to reality represents a serious failure and dereliction of duty in recording a true history of life and culture.

Russell and Winkworth’s first specific mention of photographs relates to the importance of documenting the provenance of cherished items, such as a family album, as part of a family’s history. Provenance, they explain, ‘is the life story of an item or collection and a record of its ultimate derivation and its passage through the hands of its various owners.’

While they usefully provide some interesting case histories of the step-by-step significance assessment process in action, which includes Ned Kelly items and a cabbage tree hat from around 1900, by the time they get to the Thomas Dick collection of photographs, 1910-20, under the chapter on ‘principles for good practice’, their main point is that Dick’s photographs of Aborigines are widely distributed in and out of Australia.

In regard to items of national and international significance, of particular interest, perhaps, is the reminder of the breadth of criteria to consider: Historic, Artistic or aesthetic, Scientific or research potential and Social or spiritual, before they give a summary statement of significance for Eugene von Guerard’s ‘View of Geelong’ an 1856 painting, and also the Clayton & Shuttleworth steam engine.

Their example of Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett’s remarkable film of the Gallipoli campaign which features ANZAC and British troops in military operations and daily life as well as Turkish prisoners of war and footage of the terrain, is a useful reminder that quite a few photographers also make motion pictures as well.

This is followed by the example of the Mountford-Sheard Collection of the ethnographer CP Mountford (1890-1976) which includes everything from his field notebooks to his photographs, motion pictures, sound recordings and papers, including his library. This too, the range of documentation of a photographer’s life work would also apply to some New Zealand photographers of note whose collections are not preserved in public archives.

There are positive aspects to having to assess one’s collection so it is considered for preservation these days, even when it feels more like making a job application – a competition to compete more assertively for a place in the pantheon. Having to be more articulate and critical about the content and context of our life’s work is a sobering experience, as it is to start to realise that we may have to give up any assumption that future generations will have any interest whatsoever in how we individually responded to our world with a camera.

Extremely few of the images I see on facebook, for example, seem more than a momentary twitter of dubious historical value, even when they are sourced by law enforcement seeking to identify victims or perpetrators of real or imagined misdemeanors. How many selfies do we need to be reminded of what we look like but are unworthy of being called self-portraits because they are devoid of any discernable insight?

What if we photographers could only leave for posterity no more than five per cent or less of our photographic output? That would be a big edit indeed and puts a retrospective slant on the slogan of Carl Chiarenza, the distinguished US photographer and academic who signs off his letters with “Yours for less and better photography”.

ARCHIVING FOR ARTISTS

Against the trend of institutions cutting back and wanting to cull on collections, archivists are trained to seek the whole picture. Providing context is everything for them. In an Auckland Art Gallery blog on 8 May 2020, entitled ‘Archiving for artists’, Caroline McBride, the librarian and archivist at the E H McCormick Research Library at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki provided a useful list of suggestions aimed at young as well as established practitioners. (There is no specific mention of photographers or even “Art photographers” as such, but the latter might be attracted to the idea that their favourite t-shirt or beret is worth saving as part of their legacy.)

Before you toss things out:

An archivist’s view by Caroline McBride

‘My aim is not to tell you what to do but to motivate you to think about the possibilities from how you conceive of an archive to how you store it,’ she wrote. ‘For example, do you think of your archive as essentially a solitary project or as belonging to a wider group? From a practical point of view, you will see that there are others who are available to help and interested in what you’re attempting to do. I’m just one of those people.’

Why archive?

An archive is a record that has been selected for permanent preservation. Below I outline what these ‘records’ might consist of, but let’s consider the benefits of having an archive, for you and for others. [The] benefits include:

· Archive as evidence – for example, that named and dated sketch puts you in a certain place at a certain time

· Archive as inspiration – you or another artist might like to ‘mine’ your archive for ideas in the future or you might like to return to an earlier preoccupation

· Archive for its materiality – that paint-spotted, well-loved tee shirt that you always wore in the studio has an inherent value

· Archive for exhibition – complement or contextualise your art with an item from your archive

· Archive as legacy – your archive represents you as an artist and means that not only your artwork will live on

· Archive as knowledge production – your recorded ideas and observations may illuminate your working method, motivations and interests

· Archive for cultural appreciation – your archive may contribute to a broader understanding of artistic practice at the time you are/ were working

What shall I save? What could I be creating for my archive?

Here are some ideas that researchers and artists have found useful:

Digital images or photographic prints of your artworks

A record of each of your artworks whether it be a handwritten list or a sophisticated database

Significant documents pertaining to your education, travel, influences, reading, research, exhibiting history, sales, commissions, studios and so on

Correspondence with fellow artists, curators, institutions, dealers – any communication where you discuss your art

Ephemera – whether born-digital or from the era of print, with its interesting typographies, keep exhibition invitations (both yours and to exhibitions you attended), checklists, catalogues, flyers and posters

Non-paper items – save ‘stuff’ of interest and import to your practice: clothing, samples, laminated membership cards

Creative additions:

A diary – a record of who you met, exhibitions you attended, study schedules and the like

An art journal or log – additional to or as an alternative to a listing or database that provides information and inspiration on completed or unrealised projects

A website – provide a link among your records to any website you created that hopefully reflects your current work or has been archived if no longer being maintained

Social media – indicate elsewhere where you like to post or whom/what you follow

How do I archive?

Consider how you would like your or your group’s archive to be organised. There is a guiding principle in archiving termed ‘original order’ which means that a future archivist working with your archive will attempt to keep the order evidenced at the time of hand-over (this may or may not be in your long-term plan). There are several ways an art archive can be organised: chronologically, by exhibition, by theme, by medium or series, for example, everything could simply be in pure date order or you could decide to arrange by date within a larger subject area like ‘all my sculptures’ or ‘our exhibitions’. Whatever you decide – and it would be good if this reflected your artistic working method – make available a written statement about it, even if you’ve left it mixed up because that’s how you operate.

Having decided on your ordering principle, and in relation to the list in the section above, here are some ideas:

Images – ensure that you have the best possible representation of your artworks. Research how art photographers achieve reproductions that correctly represent works: lighting, composition, colour correction, angle and so on. Learn which types of files have longevity and how to store and migrate. This video (Museums Australia, Victoria) shows you how to set up and achieve successful images with your own diy photographic studio. And for an explanation about image types, this might be a good place to start (University of Michigan Library).

Constantly review your digital content for accessibility and longevity. For the storage of both hard copy and digital images Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa has a useful guide.

Records of artwork – list (using Excel, for example) or create a database that includes for each work: title, production date, measurement, medium, image (thumbnail in this context is fine as long as you have larger-sized image files stored elsewhere), and where relevant: exhibiting history and sale details.

You can catalogue and store for free around 200 artworks (or 50MB’s worth) on a web-based database operated by Vernon Systems, e-Hive If you are managing a group archive you might like to consider the alternative Recollect (Micrographics).

Documents, correspondence and ephemera – unfold papers, lay them flat and store them in acid-free folders in conservation-standard boxes. Store in a dark, dry place with little variation in temperature. This short video, (David Ashman, Preservation Manager, Auckland Libraries) has useful information on the care and handling of your paper-based material and any CDs or DVDs you may have.

Here are two NZ suppliers for conservation standard enclosures (such as envelopes and boxes): Conservation Supplies and Port Nicholson Packaging.

Create a listing or ‘finding aid’ for your archive –it’s helpful to list and continue to list your collection. You could use Excel and create a simple numbering system, for example: Your name: Box One: Folder One, Folder Two and so on (‘Jane Doe/1/1’ for the first folder in box one and ‘Jane Doe/1/2’ for the second folder). If you choose you can list the individual items in each folder, adding a further number to the chain (an invitation within folder one of box one would have Jane Doe/1/1/1 written carefully on the back of the object and would be listed in your spreadsheet with the number and a description). Label your boxes, folders and items with conservation standard equipment.

Tips for your finding aid: use online examples; get others to look it over; use spellcheck; describe the contents, using dates and names really well to aid discovery using a keyword; publish it online if you wish to share your archive with others.

Website archiving – New Zealand’s National Library runs the NZ Web Archive and they actively seek websites to archive supplying a nomination form on their site. Digital deposits need to fit in with their collection policy but they may be interested in your offering.

Where shall I deposit my archive?

You may find that you can no longer maintain your archive or you have no further use for it. To whom should you consider donating it? In New Zealand the following three institutions have art archives: Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa and Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū. Each institution adheres to a collection acquisition policy and you could contact the relevant archivist to see find out more about this.

Large institutions provide security, access and excellent climatic conditions, however there may be other places that are better suited for your particular archive. For example, your local library or museum might be where your community is based and could be where your material would be most valuably held for the information and enjoyment of others. Wherever you choose, your archive is more likely to be accepted if it’s already well-organised.

Further considerations:

Decide and provide a written statement on how you conceive your archive and how you’d like it used: what’s okay to share and what’s off-limits. For example, given the Copyright Act 1994, are you happy to allow reproductions of your content for personal study by others (termed ‘Fair Use’)? Do you require access restrictions for some of the material because of fragility, or matters of privacy or sensitivity? Considering your output as a whole, what do you consider art and what archive, or do you not want to distinguish?

Do you have the resources you need? Archiving can be a cooperative activity and there are others from whom you can seek help: fellow artists, your community or peers, teachers, librarians, funders, collectors, curators, dealers and archivists. Lean on them, share your discoveries, get advice and if it all seems too much put all your ‘stuff’ in year-labelled boxes, store them well and hang on to them because one day you might just be grateful you did.

(‘Article written by Caroline McBride, Librarian/ Archivist, E H McCormick Research Library Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki. I should like to acknowledge Auckland Art Gallery and ARLIS/ANZ for providing support to attend The Rapidly Changing Landscape of Archive Stewardship in Contemporary Art, a symposium funded and organised by Hauser & Wirth (New York, March 2019), which was a tremendous source of ideas and inspiration.

© Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki and author’ [Caroline McBride] 2020.) https://www.aucklandartgallery.com/article/archiving-for-artists

See also Caroline McBride’s most recent blog: 'Peter Peryer: The Man in the Photograph' – An Archive and an Exhibition about their collection of the late photographer’s work.

[i] Captions for the Significance image set: Captions for the Significance image set:

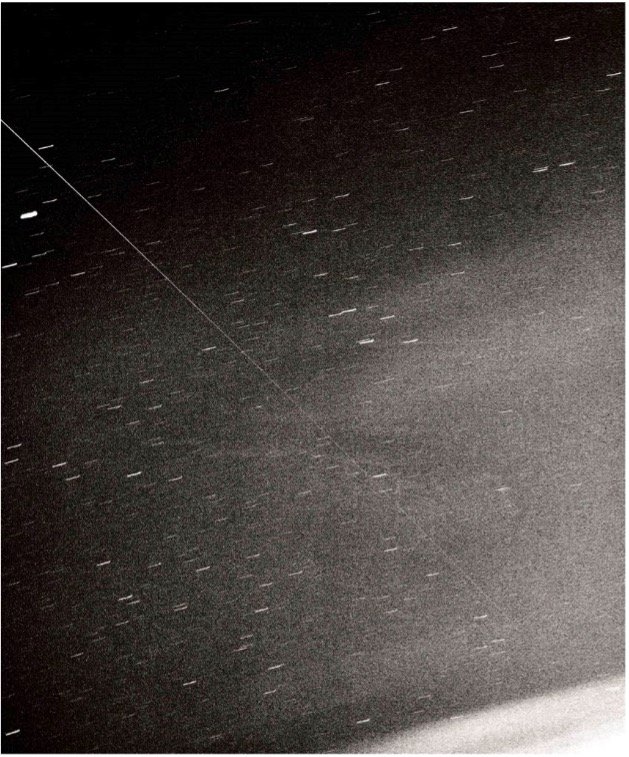

3.01: Eric Lee-Johnson: Untitled image from his historic Sputnik 1 series photographed from Waimamaku, Northland, October 1956 and widely published. From Eric Lee-Johnson: artist with a camera by John B Turner (Photoforum #64-65, 1999.)

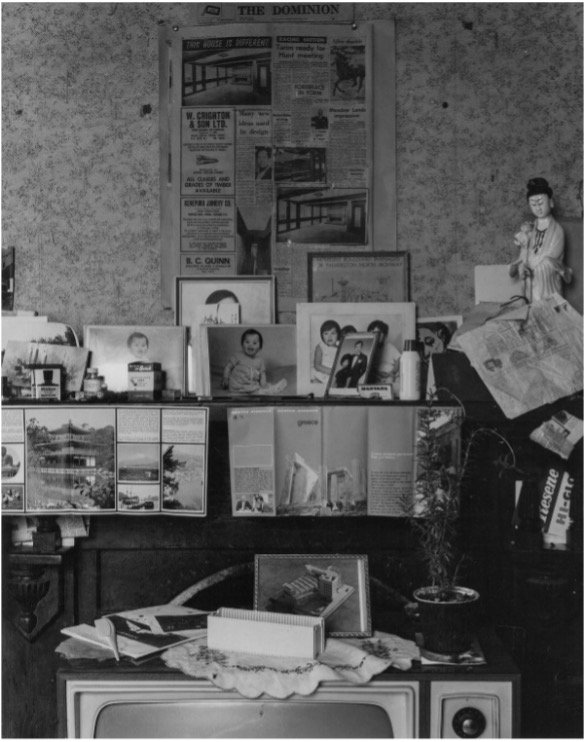

3.02: John B Turner: Interior of Lucano [Luciano] Fan's own house, Levin (Q), 1970. (JBT7001). I was commissioned by art dealer Peter McLeavey to photograph new buildings designed by Fan, a brilliant but relatively poor and misplaced architect who deserved to live in a more cosmopolitan environment.

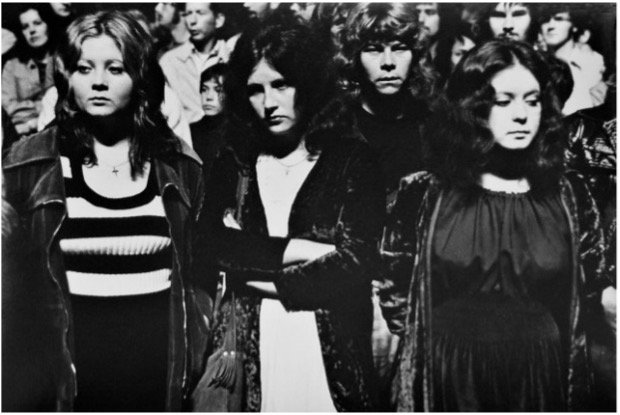

3.03: Reg Feuz: New Year’s Eve 1972 in Post Office Square, Auckland. This prolific Canadian-born photographer now retired from the Post Office in Wellington, deserves to be better known. Feuz collection

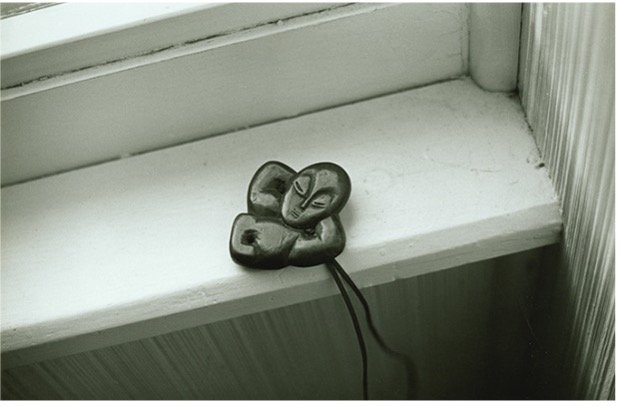

3.04: John B Turner: Len Lye's hei-tiki, photographed on the windowsill at Peter McLeavey’s Gallery, Wellington, December 1968. (JBT174-20). Unable to focus closer with my rangefinder camera, the architectural detail became a neat bed for Lye’s favourite early carving. Turner collection

3.05: Mal Turner (Attrib.): This photograph was probably made by our father soon after we moved from our Main Road, Johnsonville home. It came from my late older brother Ross Turner’s small family photographs collection and shows him on a tricycle in the foreground, along with our sister Laurice and myself (John B Turner) at the back of our two-storied Railways Department house opposite Epuni Railway Station, Lower Hutt, so can be dated around 1948. Turner collection

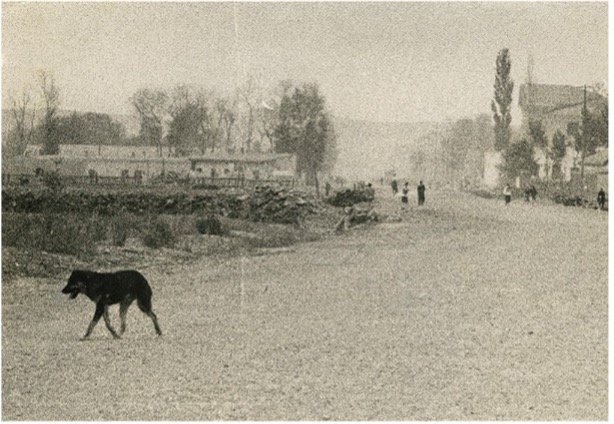

3.06: Tom Hutchins: Dry and dusty main street with dog, Urumchi, Xinjiang, China 1956, (C098-2). Tom Hutchins Images / Turner collection

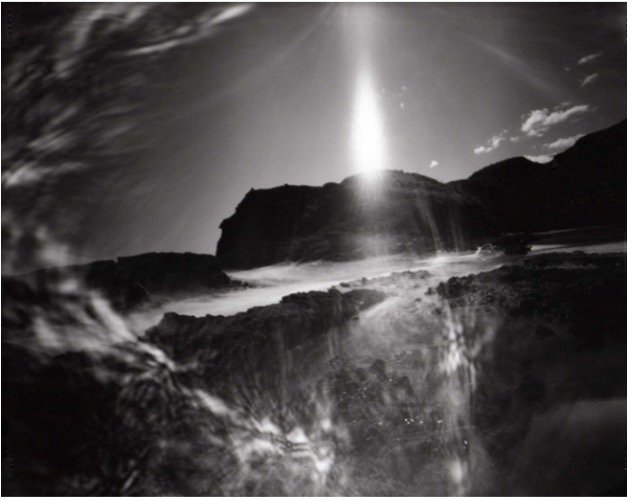

3.07: Jenny Tomlin: One of her outstanding pinhole photographs exhibited in her 2014 exhibition ‘Life beyond the lens’ at the 2014 Pingyao International Photography Festival, Shanxi, China. Tomlin collection

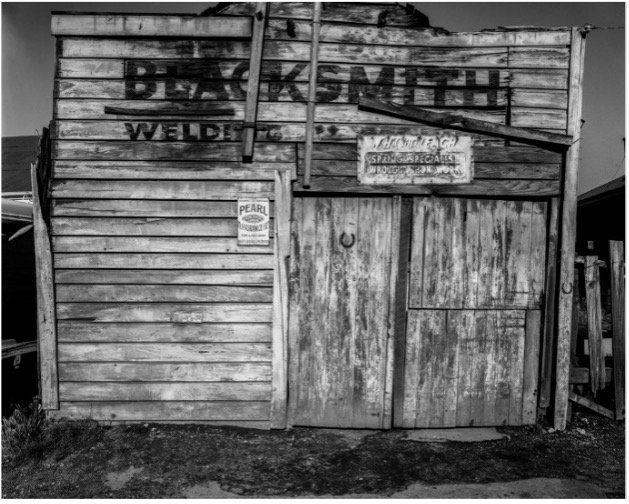

3.08: John B Turner: Blacksmith, Main Road looking east, Johnsonville, 1967. (JBT6704-1). I was learning the Zone System of exposure and development from Ansel Adams’s Basic Photo Series of books and going for maximum detail and truth to capturing the texture and look of objects. Turner collection

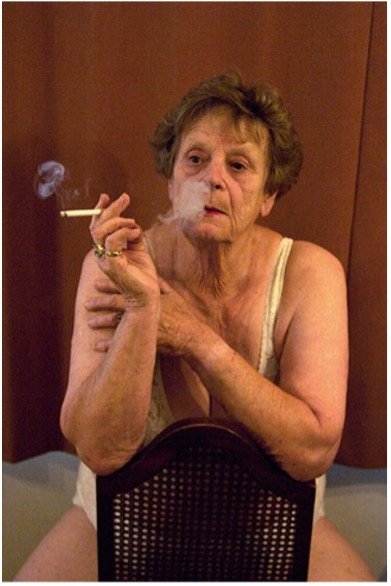

3.09: Robyn Hoonhout: ‘Jean’ 2006. This portrait of Robyn’s mother was from a series of celebratory portraits of elderly women from ‘Moment & Eternity’, at the 2011 Pingyao International Photography Festival, the first of a series of exhibitions of NZ work I have curated for them. Click here for the online catalogue

3.10: Charles Clarkson Williams: 70th birthday mock up passport by the printer in Sierra Leone including a 1963 John Turner image of him visiting the Waiwhetu Marae, Lower Hutt

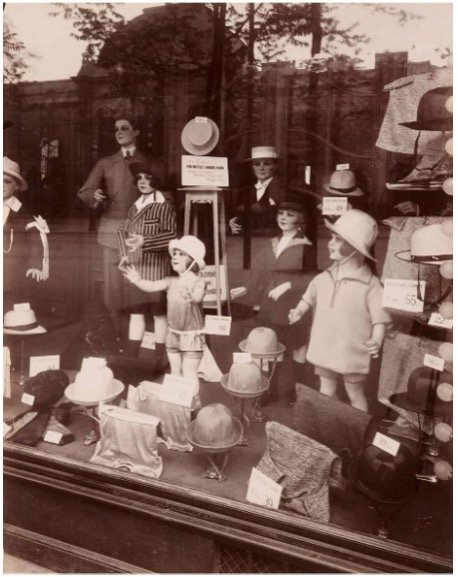

3.11: Screenshot of Eugene Atget: Magasin, Avenue des Gobelins, Paris1925, from the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York

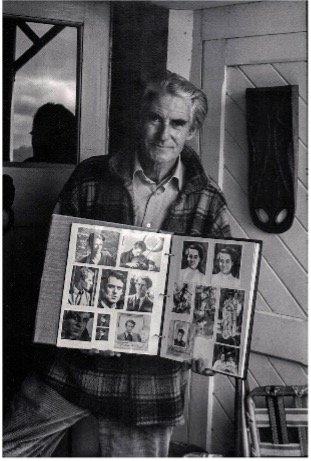

3.12: Hardwicke Knight, Broad Bay, Dunedin c1973. (JBT390-42a). The pioneering photo historian and collector at his home, showing one of many of his personal photograph albums. Turner collection

3.13: John B Turner: A failed attempt to make an abstract photograph influenced by the work of Aaron Siskind, the notable US photographer and teacher. Lower Hutt, 1967. The subject was the malthoid cladding of my home made carcase darkroom in my parents’ back garden in Waiwhetu. (JBT 6734). Turner collection

3.14: Tom Hutchins: Image from his series ‘Pictures from my window’ Pelfan Hotel, Peking (Beijing) 1956. (C010-16). Tom Hutchins Images / Turner collection

3.15: John B Turner: William (Bill Main) helping to install the ‘Research on Women’ promotion at New Zealand Display Centre, Wellington in 1968. (JBT153-5a). Bill Main was a pioneering teacher of photography at the Wellington Polytech who became a leading photo historian. Turner collection

3.16: Ian Macdonald: Rhipogonum Scanders, Heron Island, Dusky Sound, 1995. This photograph was exhibited in ‘To Save a Forest…’ photographs by leading New Zealand conservationists: Martin Hill, Ian Macdonald, Craig Potton, at the 2014 Pingyao International Photography Festival, Shanxi Province, China. Macdonald collection

3.17: Tony Carter: ‘Julie’, c 2013 from Ohura series, Ruapehu District, 2013-14. This portrait from New Plymouth photographer was one of 21 paired with portraits of people from Portland, Oregon by the Californian Kirk Crippens to contrast the nature of their characters and location, in ‘Close to home and far away’ at the 2015 Pingyao International Photography Festival. Carter collection

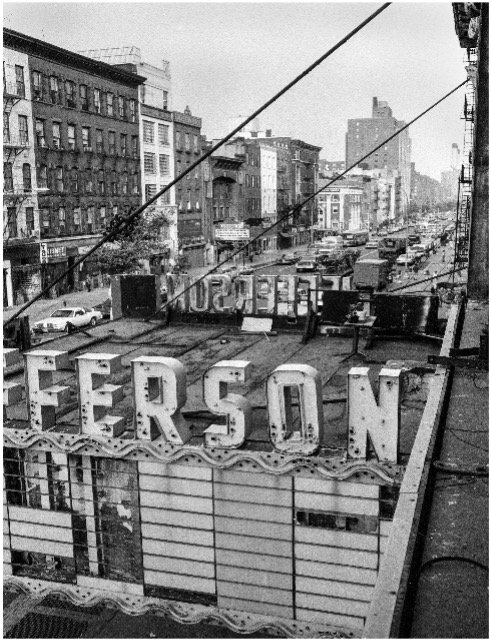

3.18: John B Turner: Street view from Helen Hartmann's studio, New York city, 1981. (JBT512-26). Turner collection_

3.19: John B Turner: Eva, Wellington, 7 June 1963. (JBT003-17a). This unspotted and unfinished portrait was one of a set trying to capture the beauty and sensuality of a girl I fancied, the daughter of a Samoan acquaintance. Turner collection

[ii] Significance 2.0: a guide to assessing the significance of collections, by Roslyn Russell and Kylie Winkworth published by the Collections Council of Australia Ltd, as an 84-page pdf in 2009. Ibid, p 12. Based on criteria proposed by Roslyn Russell and Kylie Winkworth in Significance 2.0: a guide to assessing the significance of collections, Collections Council of Australia Ltd, 2009: ‘Four primary criteria apply when assessing significance: historic, artistic or aesthetic, scientific or research potential, and social or spiritual. Four comparative criteria evaluate the degree of significance. These are modifiers of the primary criteria: provenance, rarity or representativeness, condition or completeness, interpretive capacity.’

Have your say

This investigation is ongoing, to give voice to all concerned for discussion, research, support and action on this hot topic for which we are collectively responsible to future generations.

More work is required to ascertain the views of practitioners, librarians, curators, archivists, teachers, gallerists, government, local body officials and other interested parties as to urgency, priorities, structure, best practice and action needed to improve the present situation for the common good.

We need to know if there are new and better ways of sharing the collective responsibility for sorting which photographs are worth saving, and explaining why, as objective, imaginative, and free of individual and societal biases to prevent censorship and distortion of the historical record.

We welcome case histories, personal and institutional responses, questions and alternative views, further documentation, and above all serious consideration of how problems and issues can best be resolved.

To reach the widest spectrum of those concerned, PhotoForum will be pleased to offer this complete special report free of charge as a PDF file for personal and institutional use, on the understanding that the copyright of individual contributors is respected through fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism, or review. For commercial use permission must be sought from each copyright holder.

If you wish to support our voluntary

work on this issue you can donate here:

Contact: Editor: johnbturner2009@gmail.com PhotoForum: photoforumnz@gmail.com

Acknowledgements

This is to acknowledge with thanks the generous help of many people in contributing to this investigation through their professional work in this specialist field of pictorial heritage within the social history and art spheres and for sharing their experiences and concerns here. They include Natalie Marshall and Matt Steindl at the Alexander Turnbull Library; Athol McCredie from The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Ron Brownson and Caroline McBride from the Auckland Art Gallery; Shaun Higgins at the Auckland War Memorial Museum, and Keith Giles at Auckland Libraries, in the North Island. And in the South Island, Sarah Murray and Jill Haley at the Canterbury Museum; and Ken Hall at the Christchurch Art Gallery. We are grateful to those institutions among them who have kindly allowed us to publish images of significant photographs already saved and treasured by them.

We are grateful also to feature the specific contributions of Gael Newton, Roslyn Russell and Kylie Winkworth from Australia, and Caroline McBride from Auckland, who are all leaders in their fields. Thanks are due to Barry Myers, and Max Oettli for allowing their experiences to become case histories, along with those of the late Paul C Gilbert (supported by his sister Linda Gilbert and Rim publisher Haruhiko Sameshima), and that of Tom Hutchins whose remarkable legacy I have been documenting for 30 years because he didn’t.

Valuable exhibition installation views have been provided by Mark Beatty and Paul Chapman from the Turnbull Library and Auckland Art Gallery, respectively and both Sal Criscillo and Chris Bourke who kindly made photographs of ‘The Simple Image: The photography of Barry Clothier’ exhibition at the Turnbull for me to understand its content and form..

Some of the points I wanted to make, and reminders of the important technical and practical advances brought by digital copying, had to be made with historical examples and comparisons from public or private collections. But generally, I have tried to illustrate different points with digital copies of a variety of images that I think should be preserved for posterity but have not been acquired for any public collection to the best of my knowledge and are therefore a part of the endangered species of analogue photographs at the heart of my concern. It is impossible for me to represent anything near to a full spectrum of what could be discovered either in quantity or quality simply because no audit of potential collections has been done to identify the unique content of hundreds of presently unknown collections of significant analogue work. Some of the illustrations I have added are placed to inform and challenge institutional policies which specifically exclude certain subject matter, even though I know of many cases where wisdom has prevailed to save works that otherwise would fall between categories and be lost. Guidelines are necessary, but always there can be exceptions to the rule.

More than 30 individual photographers have kindly permitted us to include one or more of their photographs in this survey, for which we are grateful, but at the same time aware that many of them belong in the category of significant photographers that no heritage department or collecting institute has approached them about the possibility of inspecting their body of work or potential custody of it for posterity when they can no longer care for their work themselves – the central theme of this blog series.

Thanks are thus due to: Peter Black, Kevin Capon, Tony Carter, David Cook, Sal Criscillo, Brian Donovan, Reg Feuz, Bernie Harfleet, Martin Hill, Murray Hedwig, King Tong Ho, Robyn Hoonhout, Megan Jenkinson, family of Sale Jessop, John Johns’ family, Hanne Johnsen, Ian Macdonald, Mary Macpherson, John Miller, Mac Miller, Barry Myers, Anne Noble, Max Oettli, Craig Potton, Doc Ross, Tom Shanahan’s family, Frank Schwere, Jenny Tomlin, Tim J Veling, Ans Westra, Wayne Wilson-Wong, and Diana Wong.

For editorial help I am most grateful to Haru Sameshima at the middle stage of restructuring this series, even when I did not always act on his advice; and also to Photoforum Web Manager Geoff Short for tidying up my messy attempt to create a series of blogs of relevance to photographers and picture specialists so they can see shared issues from each other’s point of view. The need now is for photographers and archivists to work together to ensure that photographers collections are not destroyed due to ignorance or an acute shortage of specialist staff and facilities.

Currently, despite plenty of formal policies and well thought out expressions of intentions for the preservation of our visual heritage, it is disturbing to detect so little evidence, despite the warning signs, that the official guardians of New Zealand’s visual heritage have turned a blind eye to what can be argued was one of the most active and relevant movements for the photographic recording a period of great change in New Zealand society due to a pivot away from Great Britain toward the larger world. To neglect the bodies of work by hundreds of dedicated practitioners of analogue photography from the latter half of the 20th Century, for whatever reasons, as seems to be the case, heralds a monumental disaster and mockery of our visual heritage aspirations. But with serious attention and collective action it is, hopefully, not too late to avoid that disaster which would once again see New Zealand’s photo treasures heading for the tip.

-John B Turner, Consulting Editor, Photoforum Inc.

About the editor

John B Turner was born in Porirua, New Zealand in 1943, and became an enthusiastic amateur photographer who participated in the camera club movement as a teenager. In Wellington, he worked first as a compositor at the Government Printing Office, then as a news and commercial photographer at South Pacific Photos. He was briefly a photographic printer for The Dominion newspaper, a mural printer for the National Publicity Studios, and later the photographer at the Dominion Museum (now part of The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa) during the 1960s. Before joining Tom Hutchins, the pioneering academic in photography and film, as a lecturer in photography at the Elam School of Fine Arts, University of Auckland in 1971 Turner had written widely about the medium and co-curated the exhibitions ‘Looking & Seeing’ (1968), ‘Maori in Focus’(1970). He also curated the landmark 'Nineteenth Century New Zealand Photographs’ exhibition of 1970 while working in Wellington.

From Auckland he curated 'Baigent, Collins, Fields: three New Zealand photographers’ (1973), and initiated 'The Active Eye' survey of contemporary NZ photography in 1975. The founding editor of PhotoForum magazine 1974, he has written widely on many aspects of photography for local and international publications. He was a director of Photoforum Inc., and is currently a consulting editor and contributor. He studied the history of photography with Van Deren Coke and Bill Jay, at Arizona State University, Tempe, U.S.A., in 1991, and was co-author with William Main of the anthology New Zealand Photography from the 1840s to the Present (1993). He edited and designed Ink & Silver (1995), and also Eric Lee Johnson: Artist with a Camera (1999). He was a member of the Global Nominations Panel for the Prix Pictet Prize, London, and has lived in Beijing, China since 2012, where he continues to curate shows and write about aspects of historical and contemporary photography in New Zealand and China. In 2016 with Phoebe H Li, he co-curated a survey exhibition for Beijing’s Overseas Chinese History Museum of China, titled ‘Recollections of a Distant Shore: New Zealand Chinese in Historical Images’, and co-edited and supervised the production of a bilingual book of the same title. That exhibition was later reconfigured as a year-long feature by the Auckland War Memorial Museum. Turner curated the first exhibition of Robert (Tom) Hutchins’s work for the 2016 Pingyao International Festival, and published the catalogue Tom Hutchins Seen in China 1956, with the Chinese translation and production assistance of filmmaker Han Niu. He has since placed Hutchins’s China photographs with the VCG (Visual China Group) and Getty Pictures agencies. Hutchins’ work has gained international acclaim and was featured along with Brian Brake in the Chinese language anthology China through the lens of foreign photographers (2020) and is now available in English.

Turner first exhibited his work outside of the NZ camera club and NZ Professional Photographers’ Association circles (for whose magazines he also wrote) in 1965 with a joint show with Barry Clothier at Artides Gallery, Wellington, and in the 1980s had two solo exhibitions at William Main’s Exposures Gallery in the capital city. He features in several capacities in Nina Seja’s Photoforum at 40: Counterculture, Clusters, and Debate in New Zealand (2014). In 2019 his work was included along with seven peers in ‘The New Photography’ exhibition and book about New Zealand’s first-generation contemporary photographers of the 1960s and 1970s, curated by Athol McCredie for The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

His website 'Time Exposure' is at www.jbt.photoshelter.com and you can contact him at johnbturner2009@gmail.com

The opinions expressed by the authors and editor of this report are not necessarily those of PhotoForum Inc.

We need your help to continue providing a year-round programme of online reviews, interviews, portfolios, videos and listings that is free for everyone to access. We’d also like to dream bigger with the services we offer to photographers and the visual arts.

We’ve partnered with Press Patron to give readers the opportunity to support PhotoForum Online.

Every donation helps.