NEW ZEALAND’S PHOTO TREASURES HEADING FOR THE TIP? - Part 5

Notes on the collection of photographers’ collections for posterity

A PhotoForum discussion paper by John B Turner

Part 5: Auckland Art Gallery & Alexander Turnbull Library

There is a need for collecting institutions and others… to look at the issue more broadly. What are the collections that should be preserved, when are photographers likely to be ready to part with their collections, and where would the work be best placed?

Natalie Marshall, Curator of Photographs, Alexander Turnbull Library

01: Introduction

02: Te Papa

03: Significance & Archives for Artists

04: Gael Newton: Parting with your art & Photographers’ Archives

05: Auckland Art Gallery & Alexander Turnbull Library

06: Auckland War Memorial Museum & Auckland Libraries

07: Internal Affairs & Heritage Departments

08: Canterbury Museum & Christchurch Art Gallery

09: Collection case studies: Tom Hutchins, Paul Gilbert, Max Oettli & Barry Myers

10: Curating, Barry Clothier Simple Image show & Clothier/Turner 1965 Artides show

Figure 5.01: Kevin Capon: Eric McCormick, c1985. Courtesy of the photographer

Figure 5.02: Kevin Capon: Doris Lusk, c1985. Courtesy of the photographer

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki

Ron Brownson, Senior Curator New Zealand Art, has championed photography under various directors at the Auckland Art Gallery since the 1970s and has played a major role in collecting, curating, and promoting the medium in New Zealand. He thinks that there is crisis regarding the collection of photographers’ work, collections, and in his first response to my questions pointed out some of the difficulties facing the Auckland Art Gallery:

Funding for acquisitions, or rather the small amount of funding, has always been the most critical matter in developing photographic collections…, The acquisitions funding has to cover 19th century material, early to mid-20th century material, modern photographs, [and] contemporary photographs.

That’s quite a stretch on a total annual acquisition budget of less than half a million New Zealand dollars. Which in practise has meant that many artists have found themselves subsidising the Gallery and Auckland Council through outright donations or partial or token reimbursement.

Unlike for painting, sculpture, and installation work, he indicated, the Gallery finds it more difficult to source private support of photography acquisitions. This is especially so when it comes to the retrospective collecting of earlier work. And while the erratic upwards shift in the value of photographs on the secondary market (primarily auctions) is a positive trend overall for the recognition of the importance of photography, it inevitably means the Gallery must be even more selective in what it can purchase.

I think that is an accurate assessment. But, once again, the Gallery’s commitment to collecting photography, as such, is questionable when their most experienced photography curator is not identified as such in his official capacity as a Senior Curator of New Zealand Art – a rather broad parish for which Brownson has served with distinction. But not backing up his expertise with at least a specialist assistant, to lobby for the support needed to improve their holdings of historical and contemporary photography has always seemed to me a serious handicap and significant failure of the Gallery.

Brownson, like other curators and librarians, supports the urgent need for roundtable discussions and practical solutions for how photographers deal with their analogue and digital material. Especially for those needing help to organise work covering more than four decades. The late Harvey Benge was one of many who broached this subject with him, and it is one of many issues apparently being considered by the Gallery in its current ongoing review of collection development policy and strategies to address what is or isn’t being collected.

Figure 5.03: Diana Wong: Chinese sisters Rose Wing and Ivy Wong, Auckland c1970. Courtesy of the photographer

Historically, the last staff member to have a media specific role for photography at the Gallery was Anne Kirker, who was in 1970 the first female art curator in New Zealand. Her original role as the curator of prints and drawings evolved to include photography.[i] When she left to join the then National Art Gallery (now Te Papa), Andrew Bogle subsequently took over that role in the late 1970s until his brief was changed to focus on international art around 1981. At one point the Gallery’s feeble brief for photography was restricted to only acquiring “photographs of artists”.

Figure 5.04: Craig Potton: Storm, Milford Sound, Fiordland National Park, 1993. Courtesy of the photographer

Ron observes that there is still a general lack of understanding about the significance of photographs as “visual records of cultural heritage” in the public domain. And that part of the reason might be the absence of an agreed approach, or national framework for the acquisition, display and publication of photographs. But if so, I would argue that the spread of responsibility isn’t necessarily a bad thing, when much of the vitality of the photographic scene comes from a diversity of independent organisations and inspired regional sources whose exhibitions and activities deserve but seldom receive national exposure. Overall, however, there is an argument for photography to be better represented.

Figure 5.05: Martin Hill: Burning Issues, from the Watershed Project. Tussock grass, fire. Sculpture, Albert Burn Saddle, Mount Aspiring National Park, NZ 2013. Courtesy of the photographer

The Auckland Art Gallery has seldom had targeted funding for its photography collection, even after the public declaration made by Dame Jenny Gibbs, a leading art patron and collector who said one or two decades ago that she would be inclined to focus on photography if she was just starting out as a collector. A staunch and generous supporter of the Gallery, in 1987 she also founded the Patrons of the Auckland Art Gallery which eventually replaced the Friends of the Gallery and has contributed to some key photography acquisitions in recent years. Previously, the Friends of the Gallery had formed an Acquisitions Trust in 1983 for the purpose of ‘acquisition of art works of any and every description for presentation to the Auckland City Council ... (to) be displayed in the Auckland City Art Gallery’.

Figure 5.06: Peter Black: Mathew, Rotorua, 2012. Courtesy of the photographer

The Gallery’s most expensive photographic acquisition was of Andreas Gursky’s Ocean III (2010) purchased with funds from the Graeme Maunsell Trust, M A Serra Trust, Lyndsay Garland Trust and Dingley Trust in 2012, for an undisclosed sum sufficient to buy perhaps as many as 200 or more arguably more significant and relevant NZ photographs for their collection: the very images they cannot afford to buy nearly a decade later.

Their private patrons are few and far between and mostly support the collection of living photographer’s work, with one exception being the Ilene and Laurence Dakin bequest’s purchase of historical New Zealand photographs. Currently, the Gallery has no focused sponsor or group for collecting photographs.

Brownson laments how difficult what he calls “back buying” (retrospective purchasing) can be, particularly when an artist is not already represented in their collection. They have no early Brian Brake NZ portraits, for instance, which are rare and now sell for a premium. Having assembled the most comprehensive holdings of Theo Schoon’s vintage prints in any public or private collection early on, he notes that the price of Theo Schoon’s photographs has increased exponentially since 2005. As more private collectors have appeared, he says, there have been similarly price increases for the photographs of Fiona Pardington, Lisa Reihana and Michael Parekowhai over the last decade.

(Personally, I think of inflated prices for art works which were reasonably priced when first available, as a “premium on neglect”, and that is certainly the case for some works by a small number of practitioners who find a relatively high degree of popular support for certain images.)

Brownson notes that New Zealand is far behind Australia when it comes to private funding for on-going acquisitions, and they enjoy significant benefits for the private gifting of artworks to public galleries, museums, and libraries, that we do not. Australia’s Cultural Gifts Scheme, he says, has significantly improved the acquisition of photography in Melbourne, Sydney, and Canberra’s state collections. For example, when one gallery could only afford to buy half of an important series by a distinguished ‘camera artist’, the remaining images were bought with the support of private funders and a dealer working in collaboration with the artist to ensure the complete set was acquired. Many of Brownson’s conversations with major photographers over the years have centered around finding fair ways of ensuring that, no matter what, important works could be acquired for posterity through a mix of partial gifting.

Discussion on how works need to be stored, listed, and catalogued, and dealing with the shift from analogue to digital methods were also common. Leaving an estate to deal with the contents of a photographer’s studio is rarely the best solution because the artist needs to be involved in making and directing essential decisions about their work.

Figure 5.07: David Cook: Plunket Terrace. From the ‘Jellicoe & Bledisloe’ series, 1993-1997. Courtesy of the photographer

He is well aware of how much more difficult, if not impossible it is to organise a significant exhibition when the works are spread in all directions. This, he says, particularly applies to the way Theo Schoon’s vintage photographs and late prints – indeed all his artworks – have been so widely distributed over the past 30 years, to the degree that it may be impossible to organise a truly representative exhibition of his vintage photographs. That Schoon often got others to make his prints adds another layer of complication to the task of collecting his work. And with many items selling at auction to unidentified purchasers, the task of tracking down key works is made even more difficult.

Figure 5.08: Mary Macpherson: Victoria West Street, Auckland, c2016. From ‘The Long View’ series. Courtesy of the photographer

In the early 1990s, Brownson advised the late Marti Friedlander to have her prints, proof sheets and negative/transparency material stored in archival sleeves and a database created to list the dates and specific subject matter. Fortunately, she was able to undertake this task privately, with her family trust underwriting the costs. And for other practitioners such as Gil Hanly and Max Oettli, he was able to suggest different strategies involving the support of research libraries in Auckland and Wellington as the central repositories of their negatives and digital scans of unprinted images.

By contrast, he notes how negligent newspapers often are about the documentation and preservation of their photograph collections. Unfortunately, he says, the prints and negatives of Auckland Star photographers such as Fred Freeman, Tom Hutchins, Harold Paton and other leading press photographers from the 1950s and 1960s were neither catalogued nor saved with posterity in mind. He thinks this might also be the case with the New Zealand Listener, apart from the work of Robin Morrison who retained his own transparencies and negatives which are now in the collection of the Auckland War Memorial Museum.

Figure 5.09: Anne Noble: Dead Bee Portrait #2, 2015. Courtesy of the photographer

In response to their concerns about the risk of losing vital information pertaining to the art history of New Zealand, the Auckland Art Gallery, through its E H McCormick Research Library, has become more proactive in growing its archive under the direction of the librarian and archivist Caroline McBride. Especially regarding the private records accumulated by the post-World War II generation of artists, art educators and activists now of retirement age, and those who have recently died. McBride points out that many artists’ personal papers in their library include at least a few photographs. “What we do encourage is for people to hold on to components of their archive if they’re still using them and this is what has happened in your case.”

To date, the Research Library, named after the pioneering art historian and art patron Eric McCormick (1906-1995), includes what Brownson describes as “a comprehensive representation of Len Casbolt’s work, and has a long-term loan of Marti Friedlander’s archive (since 2002), and samples of Peter Peryer’s work. They also hold the records of PhotoForum Inc and John B Turner’s archive of photographic research.”

Brownson acknowledges that gifts from prominent practitioners have been an important means of acquisition, when ideally, they deserve to be paid for in the normal way works are collected. There is a justified tone of envy when he points out that “the majority of photography acquisitions in Aotearoa are made by Te Papa, the New Zealand National Library/Alexander Turnbull Library, Auckland War Memorial Museum, and Auckland Public Libraries, which are among the most comprehensively funded”.

Figure 5.10: Megan Jenkinson: Atmospheric Optics V, 2007. Digital Lenticular pigment print on Polypropylene. Courtesy of the photographer

Brownson’s experience indicates that “the majority of ‘camera artists’ do not create their own archives as well documented and structured collections”. He cites the late Glenn Jowitt as one who made a “coherently organised library of his work over 30 years which somewhat seamlessly moved from analogue to digital”. Although Brownson observed how easily Jowitt could locate specific images in his collection, that is not how Te Papa’s Athol McCredie describes the prolific freelance photographer’s collection which they acquired after his death. As recorded in Part I of this report, McCredie is particularly concerned about the complications resulting from multiple and different-sized versions of many digital images made for different purposes, and the difficulties of deciding which version can be considered the “original” or most significant?

John B Turner: A small sampling of some of my earlier photographs for consideration by a public library or museum:

Figure 5.11: Sack Race, Petone Technical College c1958.

Figure 5.12: Street scene (The Terrace) Wellington c.1959

Figure 5.13: Images from my Johnsonville series (1966-69) included in a Photographic Society of NZ travelling National Print Portfolio, 1967. My camera club colleagues did not consider them as art works

Figure 5.14: Taxi and Johnsonville Railway Station, 1969. (JBT6909b). From the Johnsonville series

Figure 5.15: Peter McLeavey and Len Lye, Wellington, December 1968 (JBT175-13)

Figure 5.16: John B Turner: Kitchen cupboard, Lower Hutt, 1969, from Turner family series 1968-69. (JBT6944b)

Figure 5.17: John B Turner: Ross's bedroom, Lower Hutt, 1969, from Turner family series 1968-69. (JBT6949a)

Figure 5.18: John B Turner: Living room with radiogram, Lower Hutt, 1968, from Turner family series 1968-69 (JBT6875a)

Figure 5.19: L-R: John B Turner: Hamish Keith, ---Q-, and David Armitage, Auckland City Art Gallery, March 1969. (JBT187-36)

Figure 5.20: John B Turner: William Main, Exposures Gallery, Ghuznee Street, Wellington, c1985

Alexander Turnbull Library / National Library of New Zealand Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa

My very first call for gathering information on the collecting of photographers’ collections for PhotoForum was made in August 2016 to the Alexander Turnbull Library at the National Library of New Zealand in Wellington (hereinafter called the ‘National Library’ for convenience) and I was impressed to find from Natalie Marshall, their curator of photographs, how much work they had done to define and update their aims and interests.

They were being offered “over 150 photographic collections each year and were waiting for the digital tsunami to hit” she said.[ii] As a national archive the library was “acutely aware of the need to build and maintain relationships with photographers and to work with other collecting institutions to ensure important collections are preserved in the most appropriate place.” And warned that these discussions can take place over a long period of time, so it is never too soon to get the ball rolling with any photographer.

As noted in Part 1, this means that of the 120 to 200 photographic collections offered over the past three years (around three to five each week) the rejection rate has been around 70%. Whatever the outcome, investigating the diverse nature, content and size of collections and the time required to complete the process of acquisition is a lot of work and responsibility.

Marshall is acutely aware of the need to seek other homes if the National Library prefers not to take a collection for any reason. And although their guidelines clearly state that a collection might have to be broken up, in practice they have made exceptions to keep valuable material together.

...We do often speak with other collecting institutions when we are considering the acquisition of large collections, and not only photographic collections. We are acutely aware that no one institution can acquire and preserve all collections of national significance… There is a need for collecting institutions and others, such as yourself, to look at the issue more broadly. What are the collections that should be preserved, when are photographers likely to be ready to part with their collections, and where would the work be best placed?

The Library’s preference is to keep collections together, particularly significant collections, but we are bound by our collecting plan, which requires us to focus on material relating to New Zealand, the Pacific and Antarctica. We have made exceptions though, such as the Les Cleveland collection, which includes a series of photographs taken in the US. It was deemed more important to keep that collection together and the non-NZ component is a small proportion of the collection. Tom Hutchins’ collection sounds to be the other way round, which is not to say that it shouldn’t be considered by the Turnbull Library. These sorts of acquisition decisions are made by the Library, not just the curator, and would be based upon a solid assessment of the collection. We are increasingly asking for listings for large collections, especially those that cannot be appraised in person. In addition, the Library does not tend to collect three dimensional objects, so that would be part of the discussion too – which institution would be best able to keep a collection such as this together, and able to preserve and provide access to all the different components?

(Interestingly, one discussion by collecting institutions that I have not seen, is about what they do when there is a duplication of specific works, due to the nature of photography’s ability to make multiple originals? In other words, what happens when an institution inherits more virtually identical copies than it needs? As Natalie Marshall explained, “The Library is not able to deaccession; once a collection is accessioned by the Library it is here in perpetuity, adding weight to the appraisal of collections.” )

Surely then, it would make sense to seek the permission of the owner of a collection simply not to accession any surplus duplicates, so they could be redistributed later, by swapping or selling items to other collections? I am thinking of some images by prolific practitioners like Burton Bros, and Amy Harper's collection at the Auckland War Memorial Museum for example, where multiple originals can be found, but this might also apply to some contemporary practitioners. In that way both national and regional archives could both preserve relevant photographs and hedge against loss from any unforeseen local calamity.

It is not clear what the Library is doing about replacing, if that is at all possible, the many appalling low quality file copies of original photographs that they accumulated in the past before they learned to treat the original print like a delicate water colour painting and paid more attention to the quality of the prints they made from their collections of negatives. Much is owed to John Sullivan and Joan McCracken, as representatives of the new picture specialists in the 1970s who recognised that all-important difference and took steps to treat original photographic prints with proper respect as pictorial evidence and precious artifacts, well before the digital revolution closed the gap between the original and its copy.

The art of copying photographic prints before and after the digital revolution:

Figure 5.39: Digital colour copy of a faded albumen print of Burton Bros 3868: ‘At Te Ariki, Lake Tarawera’, c1885, sourced from the internet, 2022

Figure 5.40: Black & white digital version of Burton Bros 3868 image (5.39 above) with colour stripped out, 2022. Note how the colour gives the illusion of containing more detail as well as alters one’s emotional response

Figure 5.41: Digital copy of a typical analogue black and white copy from the 1960s of Burton Bros 3868. Note the general loss of definition and information in both the shadow and highlight areas, and that the original print was heavily faded at the extreme right edge. The top of the image was also cropped in the copy print. Sourced from the internet, 2022

Figure 5.42: Digital online copy of Burton Bros 3868, made from the original whole-plate glass negative, as presented by The National Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Note the higher level of detail and definition, as one would expect, but also the short tonal scale of the image which makes the scene look unnaturally flat and two dimensional. This is a universal problem perpetuated by historical image libraries that pay no heed to the subtleties and nuances of lighting and contrast that are crucial components of both objectivity and subjective expression seen in a finished print. While the black border showing the edge of the negative signifies that the negative has not been cropped, many photographers effectively cropped their pictures according to their intended purpose. (MA_I043598). Courtesy of Te Papa

Figure 5.43: Digital online copy of Burton Bros 3868, made from the original whole-plate glass negative. This copy presents itself here as both slightly darker and less contrasty than on my computer monitor

Figure 5.44: To get a better idea of the look and feel of an unfaded albumen print, a red tint has been digitally added to the slightly darkened copy of Te Papa’s insipid online offering (Figure 5.41 above) made from the original whole-plate glass negative

During the 1970s I was fortunate to be able to visit numerous museums and libraries around New Zealand and make gold-toned POP (printing out paper) contact prints directly from some selected glass plate negatives, from which often there were no known original prints. Ideally, I would have liked to make albumen prints such as those made by printing experts like James Riley and Richard Benson in the US at the time.

One example is my POP print of Alfred H Burton’s high vantage point view of ‘Koroniti (Corinth), Wanganui River’ 1985, (Burton Bros 3513) an original print of which I have never seen. I now know that the Whanganui Regional Museum has a mounted print of Burton Bros 3513, but it is badly faded as the thumbnail below shows. Burton’s ground-level view is not well-known and may be as close as one can get to an indication of what a traditional Māori village looked like before the colonial invasion, although its low-lying location may not have been typical. But the point I wish to make is that, with just a glimpse of a new European rooftop in the left background, the close view hides just how much traditional building materials were being superseded by readymade Pakeha materials and no doubt proudly displayed as progress and material advancement.

Figure 5.45: Digital thumbnail copy of Burton Bros 3868: ‘Koroniti (Corinth), Wanganui River’, 1885. Courtesy of Whanganui Regional Museum

Figure 5.46: Digital online copy of faded and damaged print of Burton Bros 3515: ‘Village Scene, Koroniti (Corinth), Wanganui River’, 1885

Figure 5.47: Alfred H Burton, BB3513: ‘Koroniti (Corinth), Wanganui River’, 1885. Gold-toned POP contact print by John B Turner from original glass whole-plate negative in the National Museum, Wellington c1973. Courtesy of Te Papa

Figure 5.48: Alfred H Burton, BB3513: ‘Koroniti (Corinth), Wanganui River’, 1885. Enlarged detail of gold-toned POP contact print by John B Turner from original glass whole-plate negative in the National Museum, Wellington c1973. This detail from the full digital image (Figure 5.46) was “spotted” to remove surface dust marks which act as a kind of visual static and interrupt the intended illusion of three-dimensionality achieved through the lighting of the subject and appropriate printing. Unfortunately, Burton Bros, the Dunedin company, seldom put in the extra effort required, such as gold toning, thorough print washing and mounting on acid free board to help ensure they would not fade over time. Courtesy of Te Papa

Among the many services now provided by the National Library is their National Preservation Office: “to help you to care for your own collections, whether they are kept in your home or a marae, library, museum or archive” which was established to assist those who hold heritage items of significance to all New Zealanders.

Information is offered on disaster recovery, and they offer workshops and seminars on preservation and conservation for libraries, museums, archives, and community groups.

They list digital resources from other Australasian institutions with expertise on different mediums, including the care of rare books, digital archives, and ‘Photographs — A guide to handling, storing, and displaying photographs safely to ensure they last as long as possible,’ as well as a guide specifically addressing the issue of ‘handling, storing, and displaying photographs’ for a marae. Guides on preserving sound recordings and even a list of funding agencies are also provided.

What they don’t do so well is to educate the public about the issues just illustrated which can make or break both the understanding and tangible experience of knowing that the images they provide of so many different subjects are a true indication of the diverse intentions and technical means used by photographers to communicate what they wanted to show and how they felt about their subject matter. The very qualities that bland representations undermine and distort. The need for the “born digital” generation to understand such issues makes it all the more urgent to attend to their education about now historical processes and tools of expression through photography.

Figure 5.49: J W Chapman-Taylor: Untitled (patient in hospital bed?) c1943. Turner Collection

Notes from the National Library of New Zealand’s ‘Collecting plan – Photographs: 2016-2018’

The full collecting plan can be inspected at https://natlib.govt.nz/about-us/strategy-and-policy/collections-policy/photographs

Collecting and priorities for the Photographic Collection

The Photographs collection is a national collection, developed to sustain in-depth research in New Zealand and Pacific studies, and to preserve documentary heritage.

The purpose of this collecting plan is to describe the extent of collecting to be undertaken, and any subsequent priorities, for the Photographs collection of the Alexander Turnbull Library, part of the National Library of New Zealand.

This collecting plan was developed in accordance with the collecting principles outlined in the National Library of New Zealand’s Collections Policy. [See below.]

Scope of the collection

The Photographs collection at the Alexander Turnbull Library is one of New Zealand’s foremost collections of photographs. The existing collection comprises approximately 1,600,000 items dating from the 1850s to the present, covering most parts of New Zealand. The collection contains a wide variety of formats, including born digital photographs.

Emphasis is placed on photographs that document New Zealand and its peoples, and support advanced research in all aspects of New Zealand studies, from the origins of photography until the present. In keeping with the objective of building a collection relevant to all New Zealanders, emphasis is placed on material of national significance.

The work of professional and amateur photographers is collected, especially that which documents significant national experiences, events, cultural practices, and social developments that have affected the lives of all New Zealanders.

Supporting material is also collected, including negative registers, indexes, and job lists.

Material that falls outside the scope of this plan may be accepted if it forms part of a larger multi-format collection that the Library wishes to acquire, or if it provides context for other items in the Library’s collections.

In addition, photographs, monographs and serials relating to the history of photography in New Zealand are also selectively collected.

Figure 5.50: John B Turner: ‘Dream Ship’ (ss Oriana), Wellington Wharf, 1961. Turner Collection

Pacific Scope: The Library selectively collects photographs relating to the Pacific Islands and Pacific Islanders, in addition to photographs of and taken by New Zealanders active in the Pacific. Priority is given to those countries that New Zealand has had a strong historical involvement and where there has been significant New Zealand activity in the Pacific, documenting the peoples, landscape (both urban and rural), and relations with New Zealand.

Antarctic Scope: The Library selectively collects photographs relating to the history of Antarctica and the Sub-Antarctic Islands, with an emphasis on photographs that involve New Zealand and New Zealanders, such as expeditions which travelled via New Zealand, and that document land and seascapes, expeditions and explorers, and natural history.

Photographs of other parts of the world may be collected where they document the experience of New Zealanders overseas, for example, where they relate to theatres of war in which New Zealanders have served or are currently serving, places associated with expatriate or travelling New Zealanders, places of origin for immigrants to New Zealand that provide context for the process of their immigration, or photographs which are regarded as antiquities as defined by the Protected Objects Act.

Figure 5.51: Murray Hedwig: Crosses, 1980. Courtesy of the photographer

Excluded from the scope of this collection are:

Non-representational or abstract photographs.*

Gallery prints, by purchase, from currently active photographers are not generally collected, with the exception of prints that assist with filling a significant gap in the collection.

Photographs in poor condition or whose physical condition poses a risk to the Library’s collections.

Copies of original photographs (digital and physical), including electronic scans. Copies lack evidential value and the Library is concentrating on collecting the most original versions of unique materials. The Library does not offer a copy and return service. **

Photographs created by government departments and other photographs covered by the Public Records Act 2005.

Collections from a community, or on a regional theme (apart from the Wellington region), which have particular relevance to their local area, where there is a suitable local collecting repository.

Collections of national significance that have a more appropriate fit with the holdings of another collecting repository.

Duplicated items or collections already held by the Alexander Turnbull Library, the National Library of New Zealand, or in another repository or institution within New Zealand. [See my comments about this aspect above.]

*[This is obviously a tricky qualification because so many photographers try their hand at making successful “abstract” (formalist) photographs, if not photograms, at one time or another to test their graphic sensibilities. Van Deren Coke, the noted art historian contended (correctly, I think), that there is no such thing as an abstract photograph compared to an abstract painting, due to it being a record of something in existence. “Semi-abstract” would therefore be a more accurate description of a photograph depicting something which is deliberately made to bamboozle the viewer and make it difficult to recognise what was in front of the camera and why the photographer is interested in the resulting combination of shapes, tones or colours – as equivalents or metaphors, perhaps, for an active mind to personally imagine and associate.]

**[It is not strictly true that a copy of an original photographic print would lack “evidential value” entirely. But there was certainly valuable information lost in the process and there are thousands of too-often inferior copies of historical images already in the Library that substitute for now damaged, lost, or hidden originals from private albums, etc. But if they fail to give an accurate idea of the original documents, the evidence that they were poorly copied in the first place is plain to see. Nevertheless, that has not stopped many a historian or family researcher publishing them without trying to find an original, even in the digital era which has revolutionised the process of creating accurate facsimiles of photographs and all two-dimensional works as never before.] [iii]

Collection strengths:

Collection strengths are identified as subject areas or formats that the Library is already strong in. Highlights in the Photographs collection include:

Portraits of Māori and Pakeha New Zealanders.

Photographs relating to the service of New Zealanders in wars and conflict zones, in particular the New Zealand Wars, the South African War, and the two World Wars.

Māori life, people and activities.

Human settlement, including rural and urban.

Major holdings of glass negatives dating from the 1860s.

Antarctica and the Sub-Antarctic Islands, including the expeditions of Scott, Shackleton and the Ross Sea Committee.

Polynesia, especially Samoa and Fiji.

Photographs from the Evening Post, The Dominion, The Press, and other newspapers.

Photographs relating to the arts, including opera, ballet, and theatre.

Work of prominent New Zealand photographers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Coverage of a wide range of historical photographic styles and processes.

Co-Collecting principles:

The National Library of New Zealand Collections Policy provides a suite of principles that guide all collecting across the published and unpublished collections by the National Library and Alexander Turnbull Library.

The relevant principles from the Collections Policy are provided below, with an explanation of how they will be realised for the Photographs collection.

Principle no 1:

Developing breadth and depth in the Library’s research collections requires decisions to be informed by, and responsive to, current and emerging research trends as well as the anticipated needs of future generations of New Zealanders.

Actions: Staff working closely with the Photographs Collection take an active role in the New Zealand research community and the New Zealand photographic community.

The Library welcomes and encourages dialogue with any part of the research and photographic communities regarding the collection of photographs that supports an existing or identified future research need.

The Library will investigate methods of active acquisition in order to develop further breadth and depth in the Photographs collection.

Of particular interest to photographers from Museum’s list of principles are the following:

Principle no 2:

Active engagement with iwi, hapū and whānau helps build collections of documentary heritage and tāonga created by Māori and relating to Māori, for the benefit of all New Zealanders.

Actions: The Library has a strong collection of photographs relating to Māori from the mid-1800s to the present, including photographs of Māori life, people and activities.

The Library welcomes input and dialogue from Māori to ensure that photographs of and by Māori are collected, preserved, and made available as appropriate and to the highest possible professional standards.

Principle no 3:

The Library has an important leadership role in collaborating and coordinating collection-related activities across institutional and national boundaries to enable New Zealanders to connect to information important to their lives and to support strong documentary heritage and tāonga collections for all New Zealanders.

Actions: The Library always considers the most appropriate repository for a collection prior to acquisition, which can often be a collegial institution within New Zealand or further abroad.

Potential areas for collaborative or coordinated proactive collecting will be explored with collegial institutions, especially when the Library’s born digital collecting capacity can be utilised.

Principle no 6: The Library takes into account the cost of acquiring, storing, managing, and making accessible collection items when building its collections.

Actions: The Library’s process for approval to purchase collection items includes consideration of cost and benefit and is followed at all times when the Crown’s acquisition budget is used to build collections.

For items that are acquired for the Photographs collection, the total cost of collecting, processing, conserving, and providing access is one factor considered as part of determining the benefit to New Zealand of having the items preserved in perpetuity as part of our documentary heritage.***

***[This principal seems reasonable because it makes little sense to waste resources. But it does raise the question of whether the accountants’ factor in the costs incurred by photographer/donors to create their collections in the first place? The Crown’s prudence is one thing, but the alternative - that of raising targeted support by private or corporate sponsorships to make up any deficit is seldom sought by library or museum leaders.]

Collecting priorities 2015 – 2018:

The Photographs collection is built to sustain advanced research in New Zealand studies and to preserve heritage taonga in perpetuity for all New Zealanders; however it is not possible to comprehensively collect photographs of national significance across all aspects of New Zealand social, economic and cultural life.

Therefore, the Library chooses to prioritise certain areas in order to focus the limited resource to either build on existing collection strengths, to fill gaps in collections, or to respond to the changing needs of researchers now and in the future. The Photographs priorities are grouped into three categories:

Ongoing priorities: Those areas in which the Library strives to build on its existing collection strengths and areas of research interest not presently well represented.

Emerging priorities: Those areas where there are signs of an emerging research trend, and therefore will require the Library to start developing strategies for photographic material to be collected to support this research need in the future.

Proactive priorities: One or two areas where there is a known gap in the Library’s collection or the national documentation and the Library proactively strives to build relationships and collect in order to fill these gaps.

The Library welcome expressions of interest and donations from a range of people, communities and organisations. However, the current priorities are provided to give a guide on areas we are likely to prefer, given limited resources. Priorities include, but are not limited to, the list provided below.

Ongoing priorities:

· New Zealanders’ experience of war

· New Zealand social history in the mid to late twentieth century

· Sport and leisure

· Businesses and business activity

· Transport and communications

· Built environment

· Farming and horticulture

· Churches and religious activity

· Domestic life

· Photographs that highlight the role and relationships of women in New Zealand society

· Gender and gender diversity

· Working class and lower socio-economic groups

· Māori life, people and activities

· Migrant and refugee communities in New Zealand

· Human impact on the environment

· Experience of expatriate New Zealanders

Proactive priorities:

· Pasifika communities in New Zealand

· New Zealand's cultural and ethnic diversity

Related collecting plans:

· New Zealand and Pacific Publications

· Ephemera

Endnotes for Part 05: Auckland Art Gallery, and Alexander Turnbull Library

[i] Anne Kirker, from 1970 was New Zealand's first female art curator in a public institution. Dr Kirker was later the curator of prints and drawings at Wellington’s National Gallery, and later became the Head of International Art, at Queensland Art Gallery, Australia. Since 2010 she has worked as an Adjunct Associate Professor at Queensland College of Art, Griffith University, in Brisbane.

[ii] For a more detailed breakdown of data as to the numbers involved see the Introduction (Part 1)

[iii] See my arguments for sourcing original photographic prints in Recollections of a Distant Shore: New Zealand Chinese in Historical Images by Phoebe H Li and John B Turner, Social Sciences Academic Press, Beijing, 2016.

Working to gain recognition for Tom Hutchins’ photography in China and the rest of the world:

(See Part 9 of this blog series for a case study on Hutchins’ collection)

Click on images to enlarge and see captions.

Acknowledgements

This is to acknowledge with thanks the generous help of many people in contributing to this investigation through their professional work in this specialist field of pictorial heritage within the social history and art spheres and for sharing their experiences and concerns here. They include Natalie Marshall and Matt Steindl at the Alexander Turnbull Library; Athol McCredie from The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Ron Brownson and Caroline McBride from the Auckland Art Gallery; Shaun Higgins at the Auckland War Memorial Museum, and Keith Giles at Auckland Libraries, in the North Island. And in the South Island, Sarah Murray and Jill Haley at the Canterbury Museum; and Ken Hall at the Christchurch Art Gallery. We are grateful to those institutions among them who have kindly allowed us to publish images of significant photographs already saved and treasured by them.

We are grateful also to feature the specific contributions of Gael Newton, Roslyn Russell and Kylie Winkworth from Australia, and Caroline McBride from Auckland, who are all leaders in their fields. Thanks are due to Barry Myers, and Max Oettli for allowing their experiences to become case histories, along with those of the late Paul C Gilbert (supported by his sister Linda Gilbert and Rim publisher Haruhiko Sameshima), and that of Tom Hutchins whose remarkable legacy I have been documenting for 30 years because he didn’t.

Valuable exhibition installation views have been provided by Mark Beatty and Paul Chapman from the Turnbull Library and Auckland Art Gallery, respectively and both Sal Criscillo and Chris Bourke who kindly made photographs of ‘The Simple Image: The photography of Barry Clothier’ exhibition at the Turnbull for me to understand its content and form..

Some of the points I wanted to make, and reminders of the important technical and practical advances brought by digital copying, had to be made with historical examples and comparisons from public or private collections. But generally, I have tried to illustrate different points with digital copies of a variety of images that I think should be preserved for posterity but have not been acquired for any public collection to the best of my knowledge and are therefore a part of the endangered species of analogue photographs at the heart of my concern. It is impossible for me to represent anything near to a full spectrum of what could be discovered either in quantity or quality simply because no audit of potential collections has been done to identify the unique content of hundreds of presently unknown collections of significant analogue work. Some of the illustrations I have added are placed to inform and challenge institutional policies which specifically exclude certain subject matter, even though I know of many cases where wisdom has prevailed to save works that otherwise would fall between categories and be lost. Guidelines are necessary, but always there can be exceptions to the rule.

More than 30 individual photographers have kindly permitted us to include one or more of their photographs in this survey, for which we are grateful, but at the same time aware that many of them belong in the category of significant photographers that no heritage department or collecting institute has approached them about the possibility of inspecting their body of work or potential custody of it for posterity when they can no longer care for their work themselves – the central theme of this blog series.

Thanks are thus due to: Peter Black, Kevin Capon, Tony Carter, David Cook, Sal Criscillo, Brian Donovan, Reg Feuz, Bernie Harfleet, Martin Hill, Murray Hedwig, King Tong Ho, Robyn Hoonhout, Megan Jenkinson, family of Sale Jessop, John Johns’ family, Hanne Johnsen, Ian Macdonald, Mary Macpherson, John Miller, Mac Miller, Barry Myers, Anne Noble, Max Oettli, Craig Potton, Doc Ross, Tom Shanahan’s family, Frank Schwere, Jenny Tomlin, Tim J Veling, Ans Westra, Wayne Wilson-Wong, and Diana Wong.

For editorial help I am most grateful to Haru Sameshima at the middle stage of restructuring this series, even when I did not always act on his advice; and also to PhotoForum Web Manager Geoff Short for tidying up my messy attempt to create a series of blogs of relevance to photographers and picture specialists so they can see shared issues from each other’s point of view. The need now is for photographers and archivists to work together to ensure that photographers collections are not destroyed due to ignorance or an acute shortage of specialist staff and facilities.

Currently, despite plenty of formal policies and well thought out expressions of intentions for the preservation of our visual heritage, it is disturbing to detect so little evidence, despite the warning signs, that the official guardians of New Zealand’s visual heritage have turned a blind eye to what can be argued was one of the most active and relevant movements for the photographic recording a period of great change in New Zealand society due to a pivot away from Great Britain toward the larger world. To neglect the bodies of work by hundreds of dedicated practitioners of analogue photography from the latter half of the 20th Century, for whatever reasons, as seems to be the case, heralds a monumental disaster and mockery of our visual heritage aspirations. But with serious attention and collective action it is, hopefully, not too late to avoid that disaster which would once again see New Zealand’s photo treasures heading for the tip.

-John B Turner, Consulting Editor, PhotoForum Inc.

About the editor

John B Turner was born in Porirua, New Zealand in 1943, and became an enthusiastic amateur photographer who participated in the camera club movement as a teenager. In Wellington, he worked first as a compositor at the Government Printing Office, then as a news and commercial photographer at South Pacific Photos. He was briefly a photographic printer for The Dominion newspaper, a mural printer for the National Publicity Studios, and later the photographer at the Dominion Museum (now part of The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa) during the 1960s. Before joining Tom Hutchins, the pioneering academic in photography and film, as a lecturer in photography at the Elam School of Fine Arts, University of Auckland in 1971 Turner had written widely about the medium and co-curated the exhibitions ‘Looking & Seeing’ (1968), ‘Maori in Focus’(1970). He also curated the landmark 'Nineteenth Century New Zealand Photographs’ exhibition of 1970 while working in Wellington.

From Auckland he curated 'Baigent, Collins, Fields: three New Zealand photographers’ (1973), and initiated 'The Active Eye' survey of contemporary NZ photography in 1975. The founding editor of PhotoForum magazine 1974, he has written widely on many aspects of photography for local and international publications. He was a former director of Photoforum Inc., and is currently a consulting editor and contributor. He studied the history of photography with Van Deren Coke and Bill Jay, at Arizona State University, Tempe, U.S.A., in 1991, and was co-author with William Main of the anthology New Zealand Photography from the 1840s to the Present (1993). He edited and designed Ink & Silver (1995), and also Eric Lee Johnson: Artist with a Camera (1999). He was a member of the Global Nominations Panel for the Prix Pictet Prize, London, and has lived in Beijing, China since 2012, where he continues to curate shows and write about aspects of historical and contemporary photography in New Zealand and China. In 2016 with Phoebe H Li, he co-curated a survey exhibition for Beijing’s Overseas Chinese History Museum of China, titled ‘Recollections of a Distant Shore: New Zealand Chinese in Historical Images’, and co-edited and supervised the production of a bilingual book of the same title. That exhibition was later reconfigured as a year-long feature by the Auckland War Memorial Museum. Turner curated the first exhibition of Robert (Tom) Hutchins’s work for the 2016 Pingyao International Festival, and published the catalogue Tom Hutchins Seen in China 1956, with the Chinese translation and production assistance of filmmaker Han Niu. He has since placed Hutchins’s China photographs with the VCG (Visual China Group) and Getty Pictures agencies. Hutchins’ work has gained international acclaim and was featured along with Brian Brake in the Chinese language anthology China through the lens of foreign photographers (2020) and is now available in English.

Turner first exhibited his work outside of the NZ camera club and NZ Professional Photographers’ Association circles (for whose magazines he also wrote) in 1965 with a joint show with Barry Clothier at Artides Gallery, Wellington, and in the 1980s had two solo exhibitions at William Main’s Exposures Gallery in the capital city. He features in several capacities in Nina Seja’s Photoforum at 40: Counterculture, Clusters, and Debate in New Zealand (2014). In 2019 his work was included along with seven peers in ‘The New Photography’ exhibition and book about New Zealand’s first-generation contemporary photographers of the 1960s and 1970s, curated by Athol McCredie for The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

His website 'Time Exposure' is at www.jbt.photoshelter.com and you can contact him at johnbturner2009@gmail.com

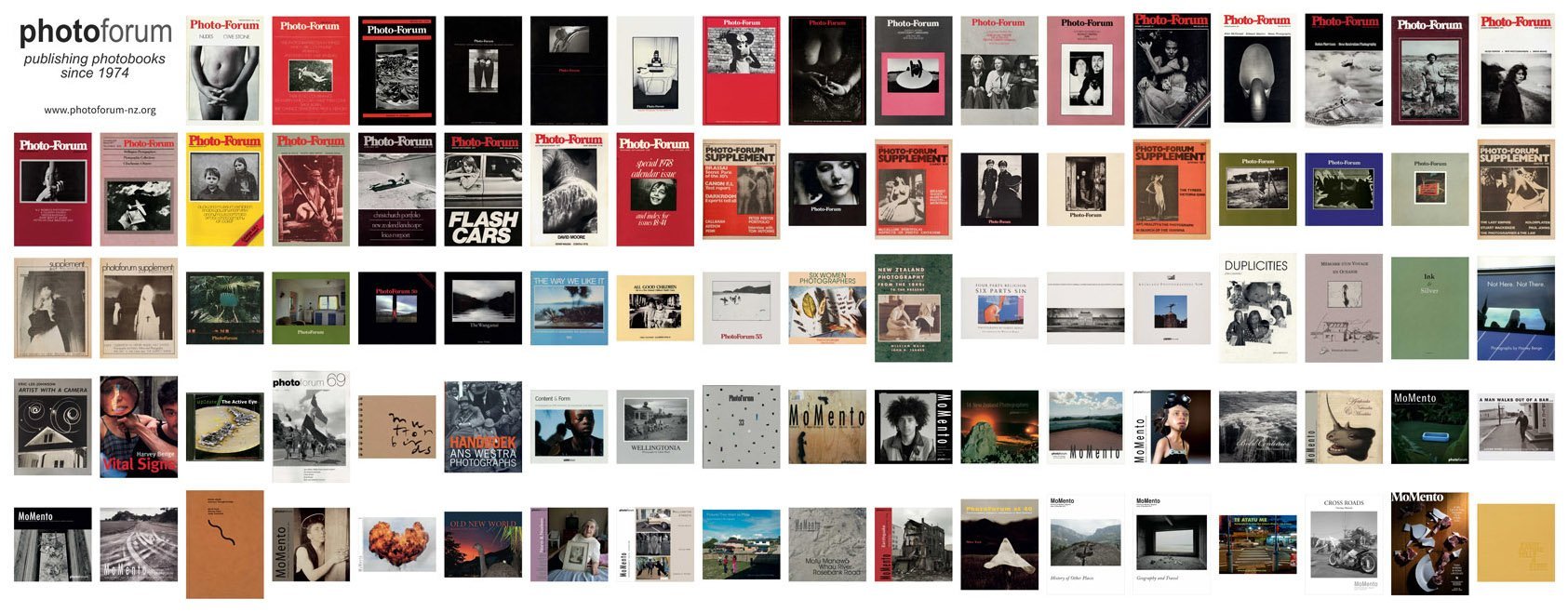

About PhotoForum

PhotoForum Inc. is a New Zealand non-profit incorporated society dedicated to the promotion of photography as a means of communication and expression. We maintain a book publication programme, and organise occasional exhibitions, workshops and lectures, and publish independent critical writing, essays, portfolios, news and archival material on this website - PhotoForum Online.

PhotoForum activities are funded by member subscriptions, individual supporter donations and our major sponsors. If you would like to join PhotoForum and receive the subscriber publications and other benefits, go to the Join page. By joining PhotoForum you also support the broader promotion and discussion of New Zealand photography that we have actively pursued since 1974.

If you wish to support the editorial costs of PhotoForum Online, you can become a Press Patron Supporter.

For more on the history of PhotoForum see here.

The opinions expressed by the authors and editor of this report are not necessarily those of Photoforum Inc.

CONTACT US:

photoforumnz@gmail.com

Photoforum Inc, PO Box 5657, Victoria Street West, Auckland 1142, New Zealand

Directors: David Cowlard & Yvonne Shaw

Consulting Editor: John B Turner: johnbturner2009@gmail.com

We need your help to continue providing a year-round programme of online reviews, interviews, portfolios, videos and listings that is free for everyone to access. We’d also like to dream bigger with the services we offer to photographers and the visual arts.

We’ve partnered with Press Patron to give readers the opportunity to support PhotoForum Online.

Every donation helps.