NEW ZEALAND’S PHOTO TREASURES HEADING FOR THE TIP? - Part 2

Notes on the collection of photographers’ collections for posterity

A PhotoForum discussion paper by John B Turner

Part 2: The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa - A conversation with Athol McCredie on collecting photography

“Even if every museum/gallery/library in the country suddenly doubled its resourcing it still wouldn’t be possible to preserve everything”

01: Introduction

02: Te Papa

03: Significance & Archives for Artists

04: Gael Newton: Parting with your art & Photographers’ Archives

05: Auckland Art Gallery & Alexander Turnbull Library

06: Auckland War Memorial Museum & Auckland Libraries

07: Internal Affairs & Heritage Departments

08: Canterbury Museum & Christchurch Art Gallery

09: Collection case studies: Tom Hutchins, Paul Gilbert, Max Oettli & Barry Myers

10: Curating, Barry Clothier Simple Image show & Clothier/Turner 1965 Artides show

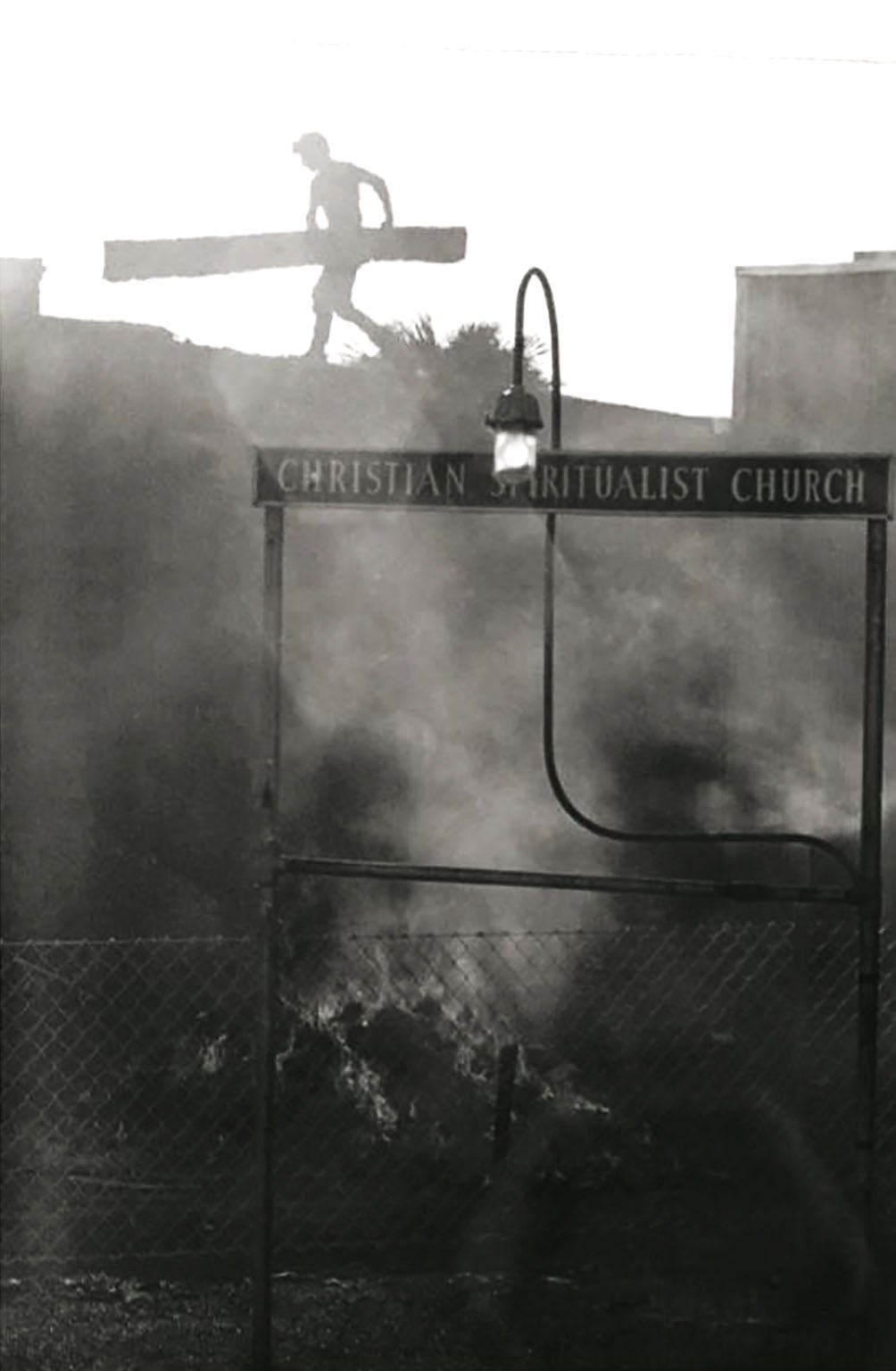

Figure 2.01: John B Turner: Cossack Vodka advertisement, west side Main Street, Johnsonville, 1969. Turner Collection (JBT69139a)

Is this a significant historical photograph?

A work of art?

Or both?

That is what specialist picture librarians, curators, archivists, and historians

are called upon to decide every day.

***

Please consider the primary criteria:

historic, artistic or aesthetic, scientific or research potential,

and social or spiritual when assessing significance [i]

Figure 2.02: Screenshot detail from The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa’s website, showing at left G Leslie Adkin’s photograph of himself pasting photographs into one of his many immaculately presented photograph albums. The illustration is a digital representation of a rough print made from Adkin’s glass negative in Te Papa’s collection.

This investigation began in June 2021 when I first approached Athol McCredie, the senior Curator of Photography at Wellington’s Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, for his thoughts on what I have come to believe is a growing crisis over the non-collection of photographers’ collections. He is the author of the monumental New Zealand Photography Collected (2015) among other major publications and is one expert who has drawn attention to the problems facing collecting institutions as a cohort of independent photographers of our generation are coming to the end of their working lives or have already died without securing a permanent home for their life’s work.

In conjunction with his survey exhibition and book The New Photography launched at Te Papa, he even organised a day long symposium on this subject for museum and library professionals in October 2019. ‘As contemporary photographers consider the future of their archives,’ he noted, ‘the institutions that collect their work face pressing questions.’

Included in his list of in-house concerns were:

Should institutions collect negatives, transparencies, and digital files when a photographer’s artistic output consists of prints derived from these?

If so, what status and use should apply to them? Should the institution be able to make prints from such source media?

What about images that were never considered worth exhibiting or publishing by the photographer?

Can or should these be regarded differently from finished works once in an institution’s collection?

How can museums, galleries and libraries manage the potential volume of photographers’ archives?

What trade-offs need to be made?

What documentation and preservation efforts are some photographers undertaking themselves?

All good questions, but the discussion did not delve into some of the critical aspects touched on, nor come up with resolutions for any of the key issues. Consequently, to answer the big issues on my mind I asked him to bring me up to date with his thoughts on aspects regarding the current state of collecting photographers’ collections.

Athol agreed that there is a crisis regarding collecting photographer’s collections and added that it is not an easy one to solve! [ii]

To get some idea I asked him what the situation was among the eight practitioners (including this writer) featured in his introduction to 1960s-1970s work in his exhibition and book The New Photography (2019).

Te Papa, he pointed out, now holds the negatives of the late photographers, John S Daley (1946-2012) and Len Wesney (1946-2017). The Alexander Turnbull Library is caring for the 1960s/1970s New Zealand negatives of Max Oettli and most of Ans Westra’s negatives and proof sheets. The collection of the late John Fields (1938-2013) is being curated on behalf of John’s widow by David Langman, of Wellington’s Galerie Langman, who is best known as the former director of the New Zealand Centre of Photography and editor of their New Zealand Journal of Photography from 2001-2008. Gary Baigent was non-committal about what will happen to his collection when I contacted him but indicated that family members would take care of it when he dies. I do not know what Richard Collins intends for his collection, but for myself I’m hoping to live long enough to prune my own collection (a daunting task), and make sure that it is better and more fully documented. I knew that the Auckland Art Gallery’s policy is not to collect negatives, but discovered that their Research Library does hold some, such as in the case of their Marti Friedlander Archive. They also encourage people to hold on to components of their archive if they’re still using them.

In conclusion, to date half of the eight photographers featured by McCredie have ended up in a suitable public archive. That’s hardly a comforting statistic, and the question is what will happen to the private collections of hundreds of other photographers deemed to have made a significant contribution to the art and visual history of New Zealand?

Under McCredie’s stewardship, Te Papa since 2001 has concentrated on acquiring individual prints and sets of work rather than acquiring whole collections, negatives and all, as his predecessor, collections manager Eymard Bradley had done, by following the tradition of the old National Museum before it was amalgamated with the National Art Gallery and absorbed as the Museum of New Zealand.

Te Papa shares with the Alexander Turnbull Library, now part of the National Library of New Zealand, and National Archives, a primary country-wide responsibility for preserving a multiplicity of historical and cultural records. In keeping with their national stature, as our regional treasure houses tend to point out, the Wellington-based archives are better funded overall. The national giants are wary of stepping on the toes of their regional cousins and actively entice them to take collections they identify as regional, or are perhaps not so keen on for one reason or another.

For individual photographers and their supporters, this means they need to think about the national vs regional significance of their work and argue for their preferred location. While it makes some sense to opt for a regional archive over a national one, when the body of work and the photographer’s family are associated with a particular region, there are associated problems when there are crossover points where regional, national, and even international significance clash with the collecting priorities of interested archives.

The most worrying outcome of well-intentioned territorial and policy briefs if they are applied not as guidelines but strict rules, is that valuable collections are sure to be lost through the cracks. (See my discussion of Tom Hutchins’ collection in Part 9 of this investigation.)

Athol McCredie and Lissa Mitchell, Te Papa’s Curator of Historical Photography, are acutely aware of the kind of crossover that occurs between collecting photographs for social history purposes on one hand and as art on the other, because Te Papa collects for both purposes. Consequently, they have around 10,000 of Ans Westra’s work prints and perhaps 200 of her exhibition prints in their collection. They also have 59 Max Oettli prints to date and around 70 of John Daley’s prints, along with a smaller number by Gary Baigent, Richard Collins, John Fields and John B Turner (the writer) from which The New Photography project arose.

Exceptions to the regional deposit concept, based on Te Papa’s responsibility to acquire large archives of national importance, meant that they acquired the collections of Frank Hofmann (1916–1989) and Glenn Jowitt (1955-2014) who were both Auckland based. They have Daley’s negatives of his personal documentary work from the 1960s and 1970s, along with his colour transparencies from his tivaevae (Cook Islands quilt making) essay and series on craftspeople but did not take his later commercial work which often adopted a documentary style. Te Papa also rescued the Christchurch-based Len Wesney’s early negatives, which were smoke damaged in the house fire that tragically took his life in 2017.[iii]

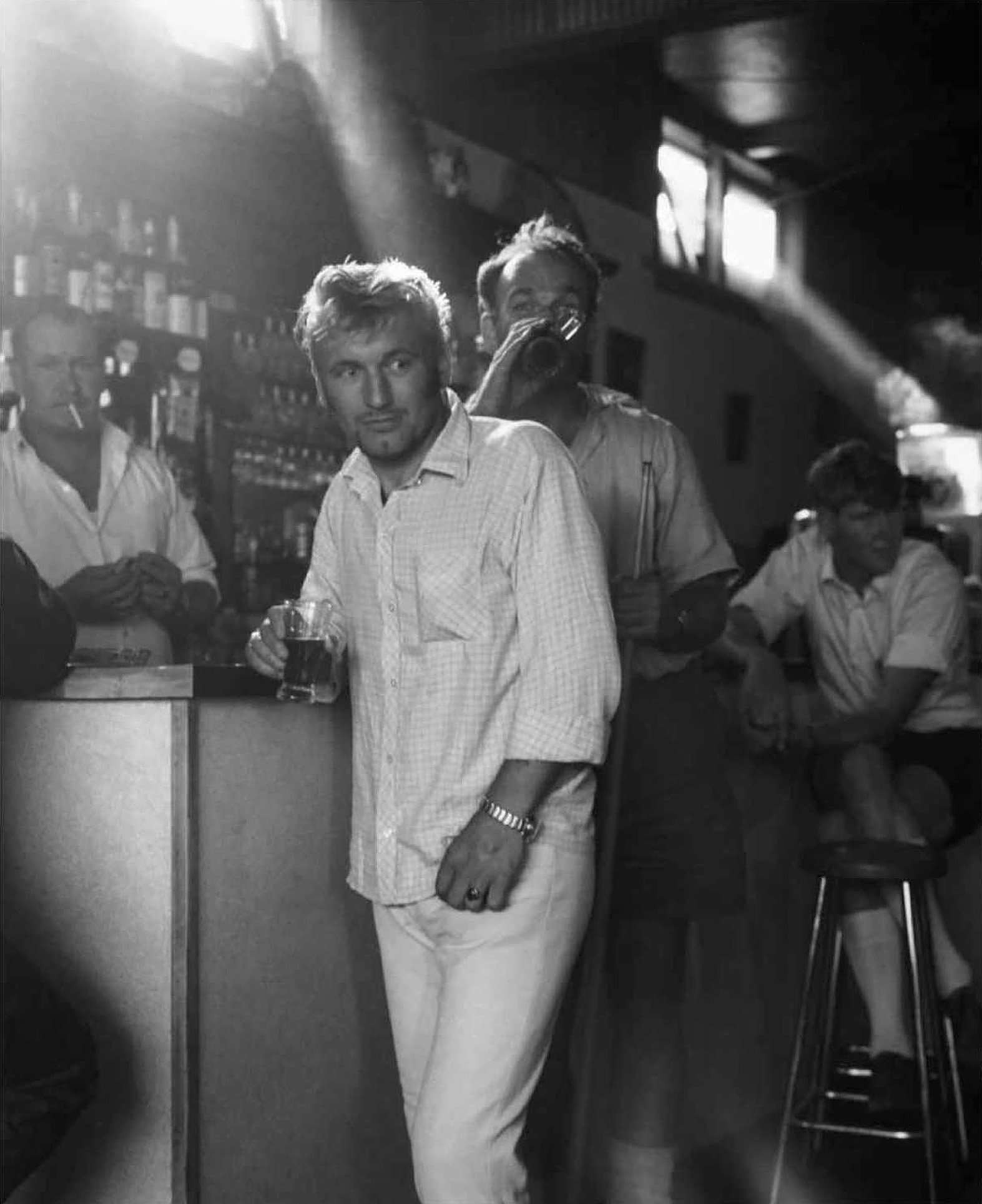

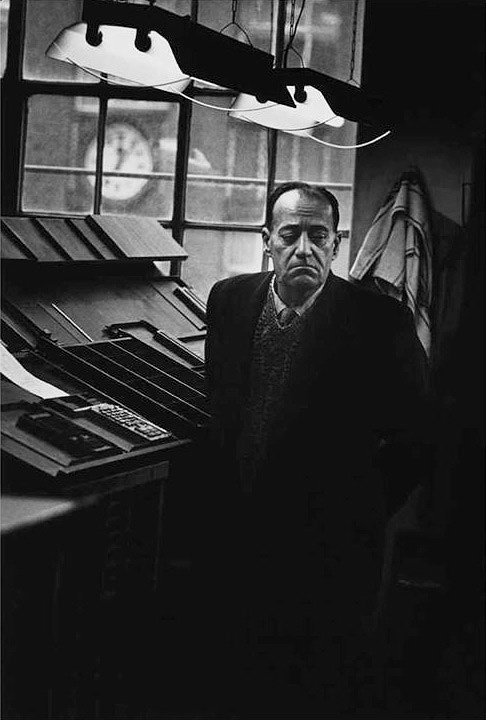

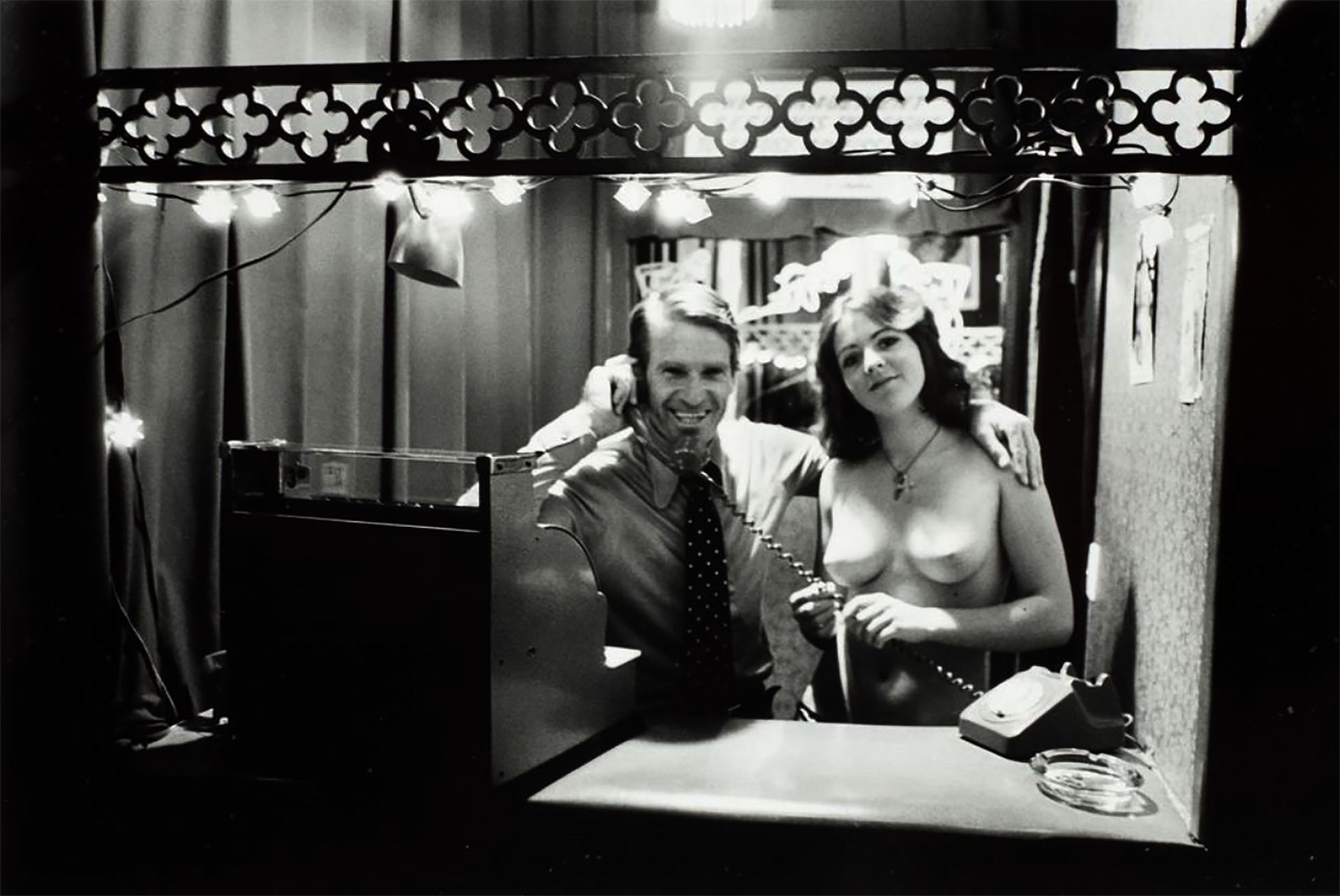

Figure 2.03: John B Turner: John Fields, Auckland 1969. Turner Collection. (JBT187-29)

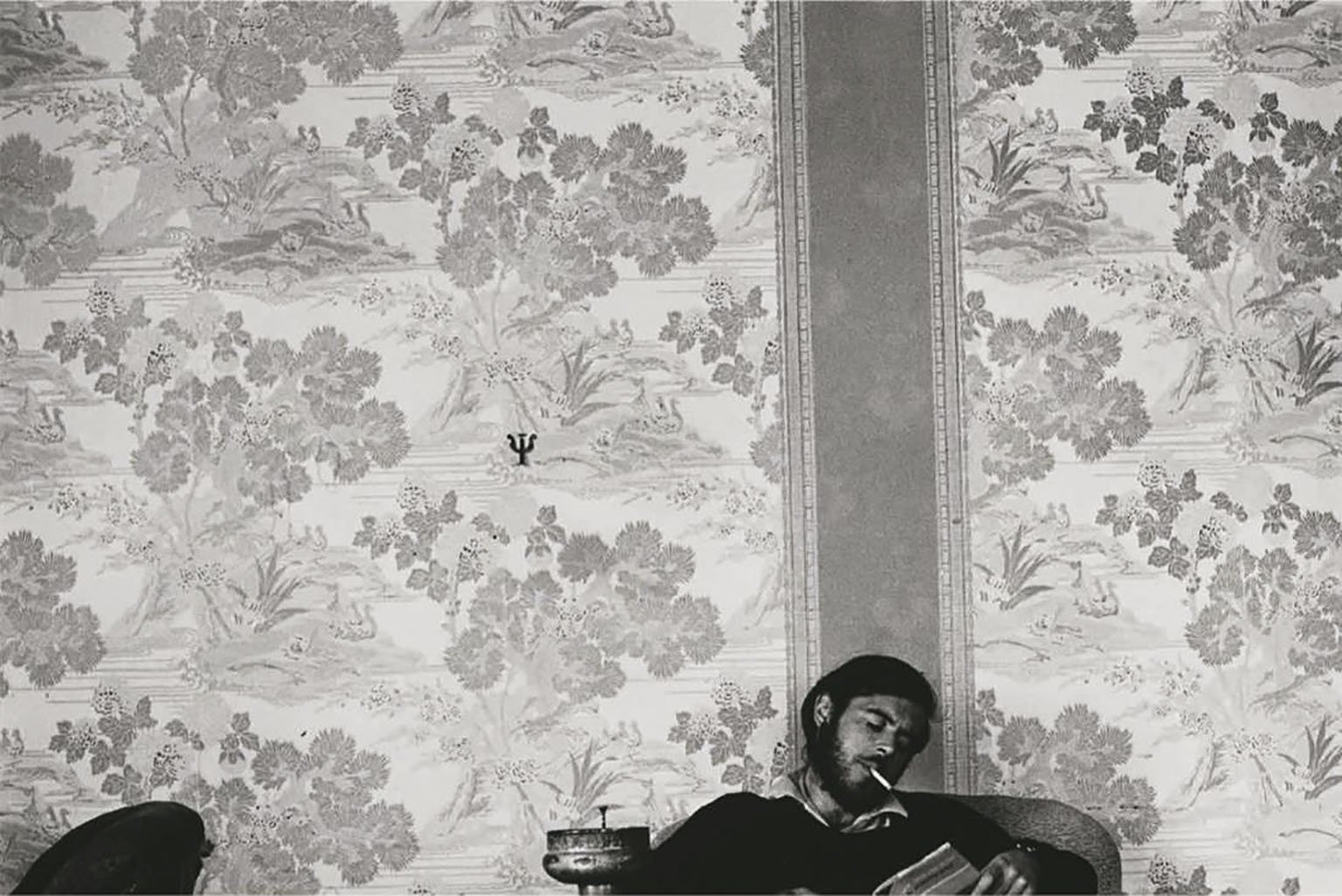

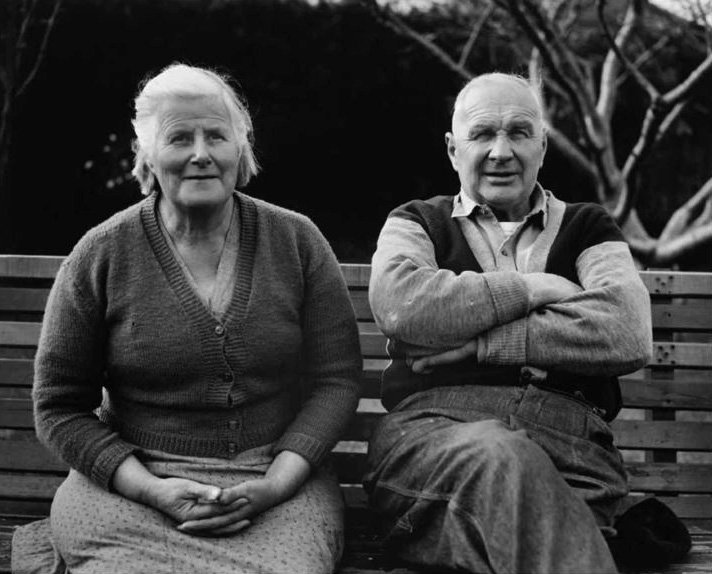

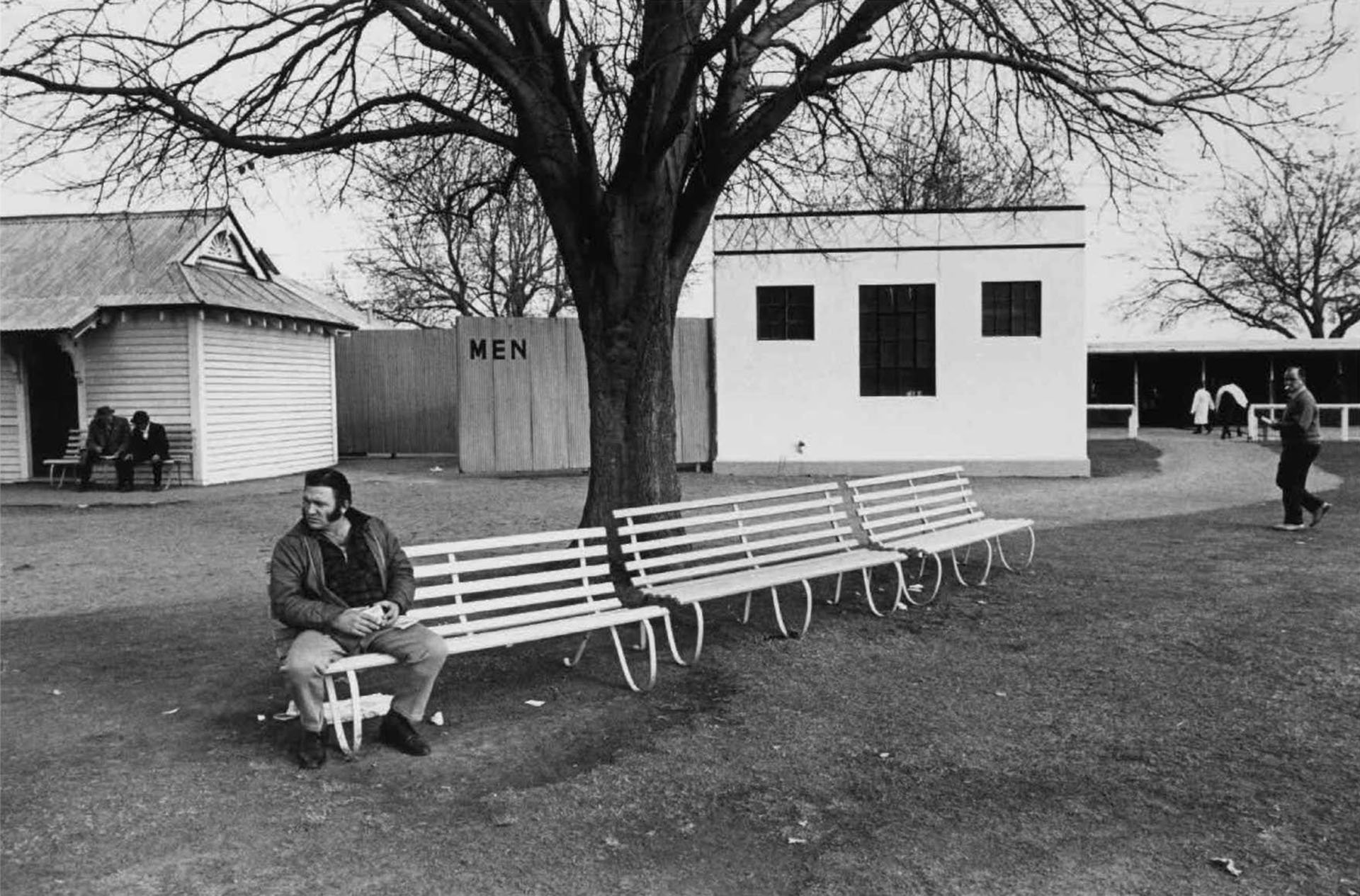

Figure 2.04: John Fields: John B Turner’s home office, Mount Eden, Auckland c.1975. Turner Collection.

For the sake of space and clarity I have edited the list of main points Athol McCredie made in response to the following four key questions:

What for you are the big issues that prevent Te Papa from being more proactive in acquiring collections?

Storage and processing resources. We [at Te Papa] are working on expanding storage for prints, but getting bigger cool stores [to protect cellulose film material] is an entirely different matter and a more difficult nut to crack; and getting more staff, which seems unlikely in the current political/financial environment.

The cool stores, he later elaborated, are not just for ‘cellulose film material’ but all glass and film negatives and transparencies, including more recent polyester based images. Cellulose nitrate films, he emphasised, need a separate store, which Te Papa doesn’t have, so it is currently sharing an only partly adequate off-site store with Nga Taonga Film and Vision for that.

What do you think should be done about this?

Try and suggest somewhere else to take large collections [to share the responsibility]? Apart from the need for more dedicated storage, he added, more specialist staff are obviously needed.

Museums the world over are short on space and staff to catalogue for all sorts of collections, not just photography, so I see solving this issue as business as usual for museums. It tends to happen incrementally, and too slowly, so you are forever behind.

Right now, he noted, the Museum has run out of space for the large, framed photographs that many contemporary photographers now make.

What can photographers do to make their collections more relevant and attractive for institutions to collect?

Documentation. Many or most of the large collections we have acquired have come with little documentation. Access these days is generally online, so when we have to describe a photograph as ‘portrait of a man, date unknown’, how is anyone going to find it online? [iv]

Filtering the work. We don’t really want multiple versions of the same shot because we have to catalogue each one. The estimated time to do so is around 15 minutes per photograph, plus the time to digitize each one and load them onto the database, etc.

Duplication; having multiple versions of basically the same picture is a big issue with digital images. Especially when a hard drive with many thousands of images contains a large proportion which are different versions of each other. Having images altered in various ways and downsized variants made for different purposes such as for Powerpoint presentations or posting on Instagram, etc., makes it more difficult and costly to try and find the ‘best’ or most ‘original’ version, when it’s not known which one the photographer considered the finished image?

Physically looking after their work properly is the other thing we would like photographers to do. We acquired a collection of negatives a while ago that had been carefully put into archival envelopes but had been stored in a basement. Many of the negatives - and their archival envelopes - had mould on them, which meant that the estate ended up wasting time and money doing what they thought was the right thing. The acetate ones amongst them had base shrinkage and deterioration. The archive had been intended to go to a public collection for a couple of decades I think, and it breaks my heart that it wasn’t offered years earlier and consequently stored in a controlled environment.

Do you consider this is a crisis in the making, or soon could be unless (what you think could/should be done about it is done)?

Yes, I do think this is a crisis and the only realistic solution is that not everyone’s work can be archived by the museum or library. So, curators have to make tough choices, but that’s the nature of our job. Even if every museum/gallery/library in the country suddenly doubled its resourcing it still wouldn’t be possible to preserve everything. Selection always will be the name of the game.

Athol then raised a batch of questions that are of particular concern to his work as a curator, such as: what is collected and why? What is the significance of the work, why it should it be preserved, and by whom? We are back to what I like to call use-value:

An issue you may not have considered is the different types of photographic practice that exist in the world. What sort of value is there in collecting all the negatives / transparencies /digital files of an “art” photographer? like, say Fiona Pardington? Isn’t the finished print the thing? What are you going to do with the negatives? You can’t print them because then you are making a simulation of what the photographer might have done.

[1] You can’t really put them online as your rendition of the negative/transparency/digital file would probably not match the photographer’s intention.

[2] Are you only ever going to hold them as a study collection so researchers can understand the photographer’s thinking and working practice?

[3] This might be worth doing with really significant photographers. But remember that 15 minutes per image cataloguing time plus imaging (say another 10 mins). With, say, 10,000 images: that’s 4,200 hours approximately, or 104 weeks (2 years). That might be fine for an Alfred Stieglitz, but for your average NZ contemporary photographer? For other photographers there can be the social documentary value of their work, even if that was unintended at the time of shooting. Max Oettli is a good case in point. Max freely admits that only a small portion of his images have aesthetic merit, but argues that many have historical value for what they depict of their time. So his negatives went to ATL [Alexander Turnbull Library], as they are mandated to collect photographs for documentary content only, but we at Te Papa have collected a decent number of his prints for their aesthetic value.

These are all interesting points, of course, and arise from the central paradox of photography as a means of communication and expression. Not least because content, context, intention, and form all play a role in the meaning and perceived value of a photograph as a work of art, or not. They can also defy attempts to be pigeon-holed by any criteria when they are stylistically identical but different from fashion photography, for example, and when they challenge prevailing conventions such as so-called “straight” photography through the so-called “conceptual art” form by Ed Ruscha, modelled on deadpan real estate photographs.

In response to some of Athol’s points (numbered in square brackets above) I offer the following rejoinders:

[1]. What are you going to do with the negatives? You can’t print them because then you are making a simulation of what the photographer might have done.

This rings true for cases where the negative/s were the starting point of subtly or heavily worked changes through technical or hand manipulations for effect by, let’s say George Chance, Fiona Pardington or Joel Peter Witkin, for example, should the need arise to reconstruct their images. But there are many examples where finely crafted reprints from the negatives of the likes of Imogen Cunningham, Dorothea Lange, August Sander, and Edward Weston do the photographers justice. The same can apply to reprints from the original negatives of Eric Lee-Johnson, Brian Brake and even those as different as Julia Margaret Cameron and Ed Ruscha that were made with artistic intent. Such facsimiles, of course, would be simulations, however convincing, but the key issue is to rigorously identify them as such. There is, after all, no other way to respectfully represent a photograph where only the negative has survived, which is all too frequently the case when there was no discernable demand for prints when it was made.

[2]. You can’t really put them online as your rendition of the negative/ transparency/digital file would probably not match the photographer’s intention

Maybe so, especially when it comes to large-scale prints, perhaps, but even then, digital copying is proving to be exceptionally accurate for replicating documents of all kinds. Once again, the central issue is to clearly label the facsimile for what it is, regardless of the ability of the viewer to discern the difference between an image and its status as an artifact. Thinking of intentionality in this way is patently not a great argument for not reproducing representations of paintings, for example, which are seen by more people than ever get to see the original.

[3] Are you only ever going to hold them [the negatives] as a study collection so researchers can understand the photographer’s thinking and working practice? That, of course all depends on the specific content and educational use-value, more than the perceived status of the practitioner, because the world is not as short of interesting and illuminating images by unidentified photographers as it is of dogged researchers. From an historical and art historical point of view there is certainly a case to be made for some, if not all, of a photographer’s negatives to be saved for such study, because they, like proof sheets, can provide vital clues for dating, identification, and context. The issue thus returns to the perceived significance of a body of work in the larger scheme of things.

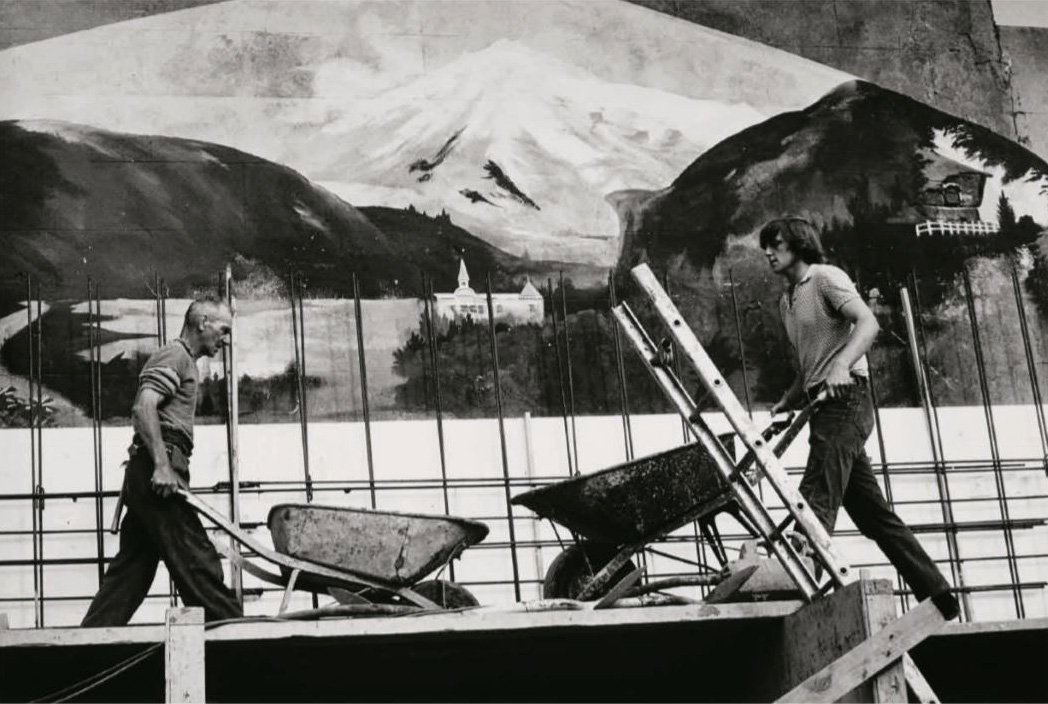

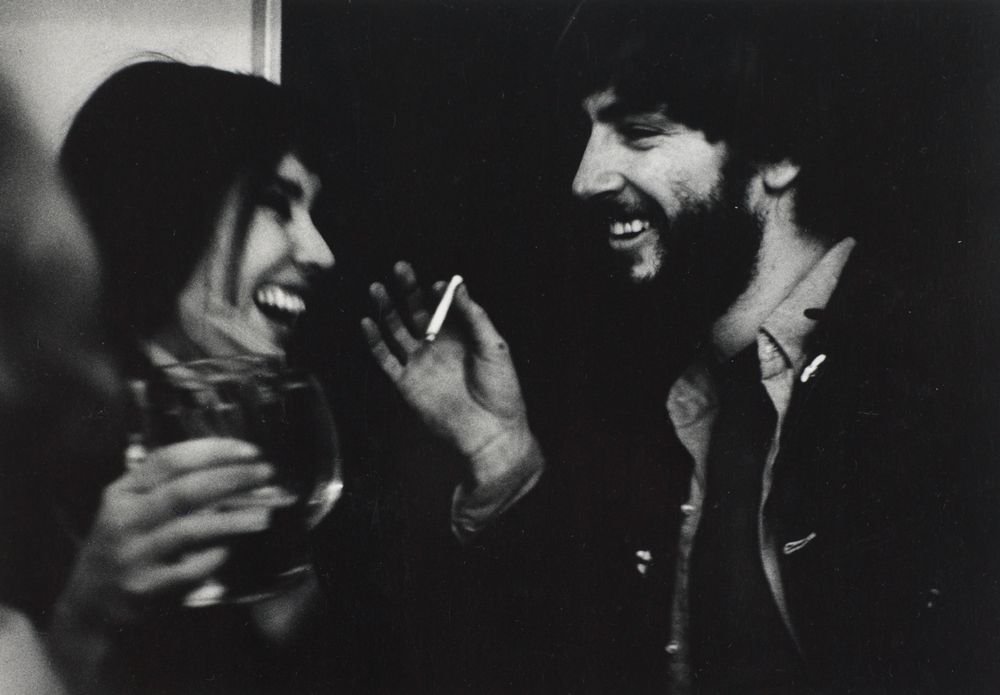

Figure 2.05: John B Turner: Detail from proof sheet of John Fields farewell NZ party at Simon and Chris Buis’s home, Woodside Road, Mt Eden, 1976, using open flash exposures (JBT377, frames 21-26). People shown include Peter Eyley, Dave King, Linda Buis, John Fields, Claudia Pond-Eyley and John Maynard.

Exhibiting and Touring Exhibitions from The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

Although one of the legislative requirements for Te Papa is ‘to exhibit, or make available for exhibition by other public art galleries, museums, and allied organisations, such material from its collections as the Board from time to time determines’, those who live outside of the capital city seldom see any of their photography exhibitions, and even fewer are seen overseas. (https://www.tepapa.govt.nz/sites/default/files/statement-of-intent-2020-24.pdf )

The notable exception is a range of traveling exhibitions made from Brian Brake’s collection which was gifted to Te Papa in 2001 by his partner Raymond Wai-man Lau, following on from their Brian Brake: China the 1950s exhibition of 1995, which was also shown at Auckland’s Fisher Gallery in Pakuranga. Brian Brake: Lens on the World, after its Wellington opening, was shown in Waikato, Rotorua, Tauranga, Christchurch, Dunedin, Hastings, Whangarei and at the Auckland Art Gallery in 2011, where I saw it and noted a significant difference from how it was hung in Wellington. And the big question is “Why aren’t there more survey or thematic exhibitions like this being created and toured by our national art museum?”

Brian Brake: Lens on China was shown alongside Kura Pounamu: Treasured stone of Aotearoa New Zealand at Beijing’s National Museum of China in November 2012 to mark the 40th anniversary of diplomatic relations between China and New Zealand, but unfortunately and characteristic for Beijing, it was accompanied with little publicity. A cutback version for smaller venues, Brian Brake: Lens on China and Japan, went to venues in Hastings, Stratford, Palmerston North, Nelson and Blenheim around 2015.

Figure 2.06. John B Turner: A section of the ‘Brian Brake: Lens on China’ exhibition shown alongside ‘Kura Pounamu: Treasured stone of Aotearoa New Zealand,’ the jade exhibition at the National Museum of China, Beijing in November 2012 to mark the 40th anniversary of diplomatic relations between China and New Zealand. (JBT20121031-0413)

Figure 2.07: John B Turner: A visitor poses with a large slab of greenstone with a mural of Brake’s famous Mitre Peak image as a backdrop at the ‘Brian Brake: Lens on China’ exhibition which was shown alongside ‘Kura Pounamu: Treasured stone of Aotearoa New Zealand,’ at the National Museum of China, Beijing in November 2012. (JBT20121031-0444)

To commemorate the 60th anniversary of the Asia Society in 2016, the Hong Kong Center in collaboration with Te Papa presented Picturing Asia: Double Take – The Photography of Brian Brake and Steve McCurry, curated by Ian Wedde with Hong Kong assistant curators Ashley Nga-sai Wu and Kristy Kwan-yi Soo. It was featured at Auckland’s Te Uru Waitakere Contemporary Gallery in 2017 and later shown at the Shanghai Center of Photography in 2018.

Athol McCredie’s landmark 2015 New Zealand Photography Collected exhibition, with around 300 “rare and fascinating” photographs, was billed as the largest photography exhibition ever held from Te Papa’s extensive collection. A drastically abbreviated version, called Public and Private - photographs of people in public and private contexts - was made for touring in New Zealand.

Te Papa’s failure to treat the New Zealand Photography Collected exhibition more seriously, however, was partly redeemed by the superb book of the same name produced by Te Papa Press, which has produced several exemplary photography publications and was at the time, perversely, under threat of closure.

Soon, as of July 2021, they will tour a small version of their Tatau: Sāmoan Tattooing exhibition with work by Mark Adams, Greg Semu and John Agcaoili. A small show called Faka–Tokelau: Living with Change, of photographs by Glenn Jowitt and Andrew Matautia is currently touring small venues.

Rather than tour their own their photographic exhibitions, Te Papa’s day by day focus is on lending items – hundreds each year – for other exhibitions in New Zealand and throughout the world; works for the Bill Culbert show currently at the Auckland Art Gallery, for example. For which, as McCredie reminds us, each item must be carefully checked for condition and possibly treated for damage or deterioration. Works have to be framed and crates made for safe travel, which might possibly require staff to travel with it to the venue, etc.

Fair enough, but there is another major reason for so few touring photography exhibitions, which is the strict - and sometimes overzealous rules imposed by the art conservationists in regard to exhibiting delicate and rare vintage prints, based on to how much light the prints will be exposed to over time. Which means, in the absence of a permanent display of our photographic treasures for students, teachers, and visitors alike, as some distinguished overseas art museums have, New Zealanders are reliant on serendipity to ever see key works displayed, and not knowing what they are missing it is unlikely they could get a special viewing appointment behind the scenes.

Van Deren Coke, the pioneering US art historian, for whom I organised a national lecture tour as a Distinguished Fulbright Visiting Professor in 1979, was astonished to find that none of the major NZ art galleries or museums he visited had a permanent display of historical photographs, and that the Auckland Art Gallery, where he outlined the advantages at a special meeting, showed no interest in the concept. As Coke admitted, from his experience at the new San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, where he formed their photography department, no matter how significant their exhibitions of paintings and other traditional arts were, the expert curators were often peeved to see that much larger crowds flocked to see the photography shows.

Questioned why his 1960s-1970s survey, The New Photography, shown at Te Papa in 2019, was not toured, Athol McCredie cited two reasons: that there was a lack of interest from other galleries, and Te Papa was hesitant to tour the show of original prints because of their general concern over conservation issues. The latter is given as the reason given for them increasingly making digital copies for their touring shows. According to conservators, a safe length of exposure for an albumen print, is around three or six months at 50 lux (darker than a typical home room light) before the print needs to be rested – not just for months but for years, the conservators estimate. By contrast a modern gelatin silver print, assumed to have been well processed and stored, can be shown for 12 months at 50 lux, and is estimated to have something like a 10-year display life before it starts to fade or stain from light exposure.

Personally, I have always found it frustrating to view exhibited prints in such dim light; and to the amusement of fellow gallery-goers I often use a torch as well as a magnifying glass to properly scrutinise them. What’s the point of preserving original prints if they can’t be seen properly? To see, or not to see? It’s an interesting paradox. I think the conservators are often too conservative when a little bit of flexibility could be injected into blanket rules. Perhaps something like a rigorous dim-lit morning and brighter-lit afternoon display advertised as such, would both protect the works and educate the audience at the same time? Or approved torches lent to visitors?

Unfortunately, this conservation issue, which is of genuine concern, undermines the educational value of seeing the original photographs and gaining insights about the specific context in which they were made. This criticism was one of the points hammered home by Geoffrey Batchen against our national museum displaying what he calls “restrikes” - new prints made from original negatives and transparencies in their collection, instead of the original objects in the 2015 New Zealand Photography Collected exhibition. He was particularly concerned about Te Papa presenting analogue copies and enlarged digital replicas as substitutes for both contemporary as well as historical originals and not correctly identifying them as such.[v]

New Zealand Photography Collected installation view, 2015. Photo Norm Heke, copyright Te Papa Tangarewa. The cabinet contains vintage prints, the large prints on the wall are recent digital prints.

Batchen made many valid observations and points, if largely from the point of view of a historian of photography and connoisseur privileged by familiarity with the photography collections of many of the best and well-resourced art museums and specialist collections around the world. Basically, he gently chided New Zealand’s national museum-cum national art depository for trying to live up to its aims and responsibilities on the cheap, regarding their collecting and representation of our photographic histories. They are, of course, also struggling to make up for their past neglect against increasing prices in the secondary market when private collectors decide to sell their treasures.

But while Batchen identified the itinerant and cut-throat nature of commercial photography in the Victorian era, he surprisingly failed to acknowledge that New Zealand, much more than Australia, lacked the population and economy of scale that created the financial backbone enjoyed by the wealthy Northern Hemisphere countries that grew fat at the expense of their colonies. One likely result of which is that some negatives, such as the many that were made on spec, appear never to have been printed because nobody wanted to buy the picture. It takes just one example to make the point, and that is the fact that while New Zealand’s photographers benefitted from the increased demand brought by the carte de visite craze for cheaper portraits started in the 1860s, few, if any, actually had the special cameras designed for making multiple small images on a single glass plate that could all be printed on a single sheet of paper and thus save time and money to increase profitability. Rather, photographers in New Zealand had to make one small image at a time, or perhaps two if they had a stereo camera, to feed the fashion, without the financial rewards enjoyed by their peers in more populous developed countries. The erratic sourcing of vital chemicals and fresh photographic paper might also help explain why it is so difficult to locate vintage prints of many of the negatives that have been rescued, such as those of a speculative nature made by the Tyree’s of Nelson and William Harding of Whanganui, for example. But this may not be so surprising when one considers that non-printing is the common fate for the majority of photographic negatives and positives ever made. It’s also a good reason, of course, for collecting negatives as well as vintage prints - if they exist - in poorer parts of the world where “restrikes” or “display prints” could introduce a new audience to the paradoxical nature of this medium which is distinguished by its unique potential use value for making what William M Ivins Jr described as “exactly repeatable visual images” (i.e. multiple originals) in his seminal history, Prints and Visual Communication of 1953. [vi]

There is no sure way to account for how a flawed exhibition or book, as much as a perfect one, can inspire a new generation of photographers and much-needed curators, critics, photo historians and influential teachers. Geoffrey Batchen’s stress on the importance of being able to study the original object and context in which it was made is just as relevant today as it was 60 years ago in New Zealand, when understanding the aesthetic potential of the photograph or modern painting as a tangible object suffered because it could only be measured from the quality of its illustration in a magazine or book, because the thing itself was nowhere in sight.

Just recently I learned that on 14 March 2018, Wayne Barrar, the Associate Head of School-Research at Massey University’s Whiti o Rehua School of Art in Wellington, had organised a seminar on ‘Photographers, Archives and Legacies’ for the College of Creative Arts to take advantage of the visit by Jem Southam, Professor of Photography at the University of Plymouth, who had been a leader in the UK movement to save photographers’ archives since 2011. A distinguished UK photographer and academic, he had been brought to Wellington to present Massey’s annual Peter Turner Memorial Lecture and also to take part in the Photobook/NZ 2018 event.

The afternoon seminar, envisioned as a “starter to try and get the institutions talking about this issue” was well received, Barrar notes. It was attended by a select group of “interested participants” nominated by Massey professor Anne Noble and Barrar, together with Natalie Marshall and Mark Strange from the National Library, and included accomplished photographers as well as picture librarians, curators, and art dealers from as far as Dunedin and Auckland, including Whanganui, and New Plymouth.

Jem Southam founded the Photographers' Archives and Legacy Project to research ‘how UK-based, independent photographers can make their work and related contextual material publicly accessible, now and for the long-term and how opportunities can be increased for the general public, researchers and students to have access to, learn about and enjoy their work.’ The Legacy Project has done extensive case studies on some of the ways in which photographers plan and organise their work and its legacy as part of their professional practice. The photographers at different career stages include Daniel Meadows, Mark Power and Liz Hingley. They are also doing case studies on the work of Michelle Sank and Southam himself.

Among UK sources Southam noted was a recent video of Terry Dennett, the former partner of Jo Spence (1934-1992) and now curator of the Jo Spence Memorial Archive, discussing the dispersal of her collection. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MOCcTT6uiak. The iconoclastic British photographer is perhaps best known for her brilliant book, Putting Myself In The Picture, A Political, Personal And Photographic Autobiography (1986). To the shame of the UK, the bulk of Spence’s archive has been acquired by Toronto’s Ryerson University in Ontario, Canada.

Have your say

This investigation is ongoing, to give voice to all concerned for discussion, research, support and action on this hot topic for which we are collectively responsible to future generations.

More work is required to ascertain the views of practitioners, librarians, curators, archivists, teachers, gallerists, government, local body officials and other interested parties as to urgency, priorities, structure, best practice and action needed to improve the present situation for the common good.

We need to know if there are new and better ways of sharing the collective responsibility for sorting which photographs are worth saving, and explaining why, as objective, imaginative, and free of individual and societal biases to prevent censorship and distortion of the historical record.

We welcome case histories, personal and institutional responses, questions and alternative views, further documentation, and above all serious consideration of how problems and issues can best be resolved.

To reach the widest spectrum of those concerned, PhotoForum will be pleased to offer this complete special report free of charge as a PDF file for personal and institutional use, on the understanding that the copyright of individual contributors is respected through fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism, or review. For commercial use permission must be sought from each copyright holder.

If you wish to support our voluntary

work on this issue you can donate here:

Contact: Editor: johnbturner2009@gmail.com PhotoForum: photoforumnz@gmail.com

Endnotes for Part 02: The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

[i] Based on criteria proposed by Roslyn Russell and Kylie Winkworth in Significance 2.0: a guide to assessing the significance of collections, Collections Council of Australia Ltd, 2009: ‘Four primary criteria apply when assessing significance: historic, artistic or aesthetic, scientific or research potential, and social or spiritual. Four comparative criteria evaluate the degree of significance. These are modifiers of the primary criteria: provenance, rarity or representativeness, condition or completeness, interpretive capacity.’

[ii] Rather than concentrate on collecting whole collections as Eymard Bradley and his predecessors had, Athol McCredie has focused on acquiring representative images from significant photographers. His colleague, curator Lissa Mitchell specialises more in historical work and research on women photographers.

[iii] As McCredie reported in The New Photography, Wesney had many of his later ‘digital images printed as small “machine prints” at a photofinishers but unfortunately the bulk of these, along with the CDs and flashcards that held the digital files were, consumed in the fire that took Len Wesney’s life in 2017. Only the prints, negatives, and transparencies from his earlier years, carefully stored under his bed, survived.’

[iv] As frustrating as this may be for cataloguing images at first, one advantage of the visual catalogue is that people successfully identifying the subject can provide the missing information.

[v] Geoffrey Batchen: ‘Reproducing History: New Zealand Photography Collected’, notes of Geoffrey Batchen’s lecture at Te Papa on 11 June 2016. This point by the then Professor of Photography at Victoria University (currently at Oxford University in England), was among several opinions deserving challenge, in his erudite critique of the exhibition then on display, a written copy of which he kindly sent me on request.

Included in his observations were the following facts and opinions, here paraphrased: Most of the exhibited photographs were not in fact vintage prints. ‘Most of them are instead inkjet prints made from scans taken from negatives or transparencies in Te Papa’s collections. They were produced only last year, sometimes 140 years after their exposure, at sizes determined, not by the photographer, but by the exhibition’s curator and his design team.

“They are restrikes, to use a printer’s term, or, if you like, reproductions from photographs, or, to use Te Papa’s own term, “display prints”.’

‘Just for the record, I’ve never seen ‘display prints’ of this kind exhibited in this manner in any national gallery anywhere else in the world. In fact the last time I saw such an extensive use of ‘display prints’ was in 2011 during the Brian Brake exhibition here at Te Papa. It seems to have become the curatorial house style.

‘So the ethics of the making and showing of such prints is obviously a topic we should discuss today, along with the ramifications of such a practice for our understanding of New Zealand’s history and Te Papa’s function.

‘…. In other words, in this exhibition we have photographs treated as vehicles for information, as abstract “images,” not as physical objects with specific attributes and histories that are tied to a specific place “in the real world.”

‘…. The Brake image is listed in Athol’s book as a “35mm colour transparency” but is presented here as another of these contemporary inkjet prints. It is therefore being shown to us as it was never seen during Brake’s lifetime.’

‘ …. By ignoring the difference between negatives and positives, or between vintage and recent prints, and by transforming its photographs from one medium into another at will, the exhibition declares (in an amazing declaration for an art museum) that medium doesn’t matter. By rejecting decisions made by their makers about tonal range or size, Te Papa assumes the photographs in its collections are simply available for plunder, to be used in whatever ways suit the curator’s preferences or the museum’s pedagogical aims.

‘This brings us back to where we started. As I suggested then, New Zealand Photography Collected is an exhibition that has a lot to say about photography, about New Zealand, and about Te Papa. But it mostly tells us about Te Papa.’

[vi] While arguing that Te Papa should display Brian Brake’s actual colour transparencies as originals, instead of making enlargements for exhibition, Geoffrey Batchen overlooked the fact that Brake often exhibited mural-sized prints from both his colour and black and white negatives. Nevertheless, it does seem that Te Papa put too little time into what could and should have been a more respectable and informative exhibition to match the book that outclassed it.

Acknowledgements

This is to acknowledge with thanks the generous help of many people in contributing to this investigation through their professional work in this specialist field of pictorial heritage within the social history and art spheres and for sharing their experiences and concerns here. They include Natalie Marshall and Matt Steindl at the Alexander Turnbull Library; Athol McCredie from The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Ron Brownson and Caroline McBride from the Auckland Art Gallery; Shaun Higgins at the Auckland War Memorial Museum, and Keith Giles at Auckland Libraries, in the North Island. And in the South Island, Sarah Murray and Jill Haley at the Canterbury Museum; and Ken Hall at the Christchurch Art Gallery. We are grateful to those institutions among them who have kindly allowed us to publish images of significant photographs already saved and treasured by them.

We are grateful also to feature the specific contributions of Gael Newton, Roslyn Russell and Kylie Winkworth from Australia, and Caroline McBride from Auckland, who are all leaders in their fields. Thanks are due to Barry Myers, and Max Oettli for allowing their experiences to become case histories, along with those of the late Paul C Gilbert (supported by his sister Linda Gilbert and Rim publisher Haruhiko Sameshima), and that of Tom Hutchins whose remarkable legacy I have been documenting for 30 years because he didn’t.

Valuable exhibition installation views have been provided by Mark Beatty and Paul Chapman from the Turnbull Library and Auckland Art Gallery, respectively and both Sal Criscillo and Chris Bourke who kindly made photographs of ‘The Simple Image: The photography of Barry Clothier’ exhibition at the Turnbull for me to understand its content and form..

Some of the points I wanted to make, and reminders of the important technical and practical advances brought by digital copying, had to be made with historical examples and comparisons from public or private collections. But generally, I have tried to illustrate different points with digital copies of a variety of images that I think should be preserved for posterity but have not been acquired for any public collection to the best of my knowledge and are therefore a part of the endangered species of analogue photographs at the heart of my concern. It is impossible for me to represent anything near to a full spectrum of what could be discovered either in quantity or quality simply because no audit of potential collections has been done to identify the unique content of hundreds of presently unknown collections of significant analogue work. Some of the illustrations I have added are placed to inform and challenge institutional policies which specifically exclude certain subject matter, even though I know of many cases where wisdom has prevailed to save works that otherwise would fall between categories and be lost. Guidelines are necessary, but always there can be exceptions to the rule.

More than 30 individual photographers have kindly permitted us to include one or more of their photographs in this survey, for which we are grateful, but at the same time aware that many of them belong in the category of significant photographers that no heritage department or collecting institute has approached them about the possibility of inspecting their body of work or potential custody of it for posterity when they can no longer care for their work themselves – the central theme of this blog series.

Thanks are thus due to: Peter Black, Kevin Capon, Tony Carter, David Cook, Sal Criscillo, Brian Donovan, Reg Feuz, Bernie Harfleet, Martin Hill, Murray Hedwig, King Tong Ho, Robyn Hoonhout, Megan Jenkinson, family of Sale Jessop, John Johns’ family, Hanne Johnsen, Ian Macdonald, Mary Macpherson, John Miller, Mac Miller, Barry Myers, Anne Noble, Max Oettli, Craig Potton, Doc Ross, Tom Shanahan’s family, Frank Schwere, Jenny Tomlin, Tim J Veling, Ans Westra, Wayne Wilson-Wong, and Diana Wong.

For editorial help I am most grateful to Haru Sameshima at the middle stage of restructuring this series, even when I did not always act on his advice; and also to Photoforum Web Manager Geoff Short for tidying up my messy attempt to create a series of blogs of relevance to photographers and picture specialists so they can see shared issues from each other’s point of view. The need now is for photographers and archivists to work together to ensure that photographers collections are not destroyed due to ignorance or an acute shortage of specialist staff and facilities.

Currently, despite plenty of formal policies and well thought out expressions of intentions for the preservation of our visual heritage, it is disturbing to detect so little evidence, despite the warning signs, that the official guardians of New Zealand’s visual heritage have turned a blind eye to what can be argued was one of the most active and relevant movements for the photographic recording a period of great change in New Zealand society due to a pivot away from Great Britain toward the larger world. To neglect the bodies of work by hundreds of dedicated practitioners of analogue photography from the latter half of the 20th Century, for whatever reasons, as seems to be the case, heralds a monumental disaster and mockery of our visual heritage aspirations. But with serious attention and collective action it is, hopefully, not too late to avoid that disaster which would once again see New Zealand’s photo treasures heading for the tip.

-John B Turner, Consulting Editor, Photoforum Inc.

About the editor

John B Turner was born in Porirua, New Zealand in 1943, and became an enthusiastic amateur photographer who participated in the camera club movement as a teenager. In Wellington, he worked first as a compositor at the Government Printing Office, then as a news and commercial photographer at South Pacific Photos. He was briefly a photographic printer for The Dominion newspaper, a mural printer for the National Publicity Studios, and later the photographer at the Dominion Museum (now part of The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa) during the 1960s. Before joining Tom Hutchins, the pioneering academic in photography and film, as a lecturer in photography at the Elam School of Fine Arts, University of Auckland in 1971 Turner had written widely about the medium and co-curated the exhibitions ‘Looking & Seeing’ (1968), ‘Maori in Focus’(1970). He also curated the landmark 'Nineteenth Century New Zealand Photographs’ exhibition of 1970 while working in Wellington.

From Auckland he curated 'Baigent, Collins, Fields: three New Zealand photographers’ (1973), and initiated 'The Active Eye' survey of contemporary NZ photography in 1975. The founding editor of PhotoForum magazine 1974, he has written widely on many aspects of photography for local and international publications. He was a director of Photoforum Inc., and is currently a consulting editor and contributor. He studied the history of photography with Van Deren Coke and Bill Jay, at Arizona State University, Tempe, U.S.A., in 1991, and was co-author with William Main of the anthology New Zealand Photography from the 1840s to the Present (1993). He edited and designed Ink & Silver (1995), and also Eric Lee Johnson: Artist with a Camera (1999). He was a member of the Global Nominations Panel for the Prix Pictet Prize, London, and has lived in Beijing, China since 2012, where he continues to curate shows and write about aspects of historical and contemporary photography in New Zealand and China. In 2016 with Phoebe H Li, he co-curated a survey exhibition for Beijing’s Overseas Chinese History Museum of China, titled ‘Recollections of a Distant Shore: New Zealand Chinese in Historical Images’, and co-edited and supervised the production of a bilingual book of the same title. That exhibition was later reconfigured as a year-long feature by the Auckland War Memorial Museum. Turner curated the first exhibition of Robert (Tom) Hutchins’s work for the 2016 Pingyao International Festival, and published the catalogue Tom Hutchins Seen in China 1956, with the Chinese translation and production assistance of filmmaker Han Niu. He has since placed Hutchins’s China photographs with the VCG (Visual China Group) and Getty Pictures agencies. Hutchins’ work has gained international acclaim and was featured along with Brian Brake in the Chinese language anthology China through the lens of foreign photographers (2020) and is now available in English.

Turner first exhibited his work outside of the NZ camera club and NZ Professional Photographers’ Association circles (for whose magazines he also wrote) in 1965 with a joint show with Barry Clothier at Artides Gallery, Wellington, and in the 1980s had two solo exhibitions at William Main’s Exposures Gallery in the capital city. He features in several capacities in Nina Seja’s Photoforum at 40: Counterculture, Clusters, and Debate in New Zealand (2014). In 2019 his work was included along with seven peers in ‘The New Photography’ exhibition and book about New Zealand’s first-generation contemporary photographers of the 1960s and 1970s, curated by Athol McCredie for The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

His website 'Time Exposure' is at www.jbt.photoshelter.com and you can contact him at johnbturner2009@gmail.com

The opinions expressed by the authors and editor of this report are not necessarily those of PhotoForum Inc.

We need your help to continue providing a year-round programme of online reviews, interviews, portfolios, videos and listings that is free for everyone to access. We’d also like to dream bigger with the services we offer to photographers and the visual arts.

We’ve partnered with Press Patron to give readers the opportunity to support PhotoForum Online.

Every donation helps.